Affair of Fielding and Bylandt facts for kids

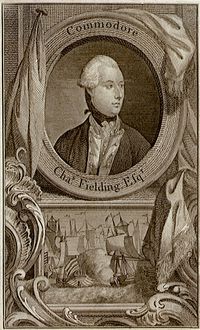

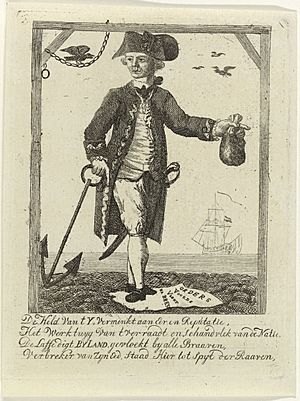

The affair of Fielding and Bylandt was a short naval clash that happened near the Isle of Wight on December 31, 1779. It involved a British navy group, led by Commodore Charles Fielding, and a Dutch navy group, led by rear-admiral Lodewijk van Bylandt. The Dutch group was protecting a convoy of merchant ships.

At this time, the Dutch and British were not officially at war. However, the British wanted to check the Dutch merchant ships. They believed these ships might be carrying goods that were considered `contraband` (illegal items) to France. France was then fighting against Britain in the American Revolutionary War.

Admiral Bylandt tried to avoid a fight by offering to show the British the ships' lists of goods. But Commodore Fielding insisted on physically searching the ships. Bylandt then put up a brief show of force, firing a few shots, before `striking his colours` (lowering his flag as a sign of surrender). The British then took the Dutch merchant ships as `prizes` (captured ships) to Portsmouth. The Dutch navy group followed them.

This incident made the already difficult relationship between Great Britain and the Dutch Republic even worse. It also helped lead to the creation of the First League of Armed Neutrality. This was a group of neutral countries that agreed to protect their shipping rights. The Dutch joined this group in December 1780. Because the Dutch were secretly helping the American rebels, Britain declared the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War soon after.

Contents

Why it Happened: The Background

After some conflicts in the late 1600s, the Dutch Republic had become a strong friend of Great Britain. At first, the Dutch were the more powerful partner, but by the 1700s, Britain became stronger. The Dutch had signed treaties that meant they had to offer military help if Britain asked.

However, the Dutch also had a special agreement from the Treaty of Breda (1667) and the Commercial Treaty of 1668. This agreement allowed them to carry non-contraband goods on their ships to countries Britain was fighting. These goods could not be seized, even if they belonged to people from enemy countries. This was known as "free ship, free goods."

The treaties defined `contraband` very narrowly, meaning only "arms and munitions" (weapons and ammunition). Items like `naval stores` (materials for building ships, such as timber, masts, rope, and tar) were not considered contraband. This right became very important during wars where Britain was involved but the Dutch Republic remained neutral. For example, during the Seven Years' War and after 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. In this war, Britain was fighting against the American colonies and their allies, France and Spain.

This special right meant that British ships couldn't easily inspect Dutch ships or take their goods. This made it harder for Britain to stop trade with its enemies, especially since Dutch shipping was a big part of European trade at the time.

Even though many people in the Dutch Republic supported the American Revolution after 1776, the Dutch government was mostly controlled by the `stadtholder` (a leader similar to a head of state), William V, Prince of Orange. He was against helping the Americans.

However, the Dutch Republic was made up of many independent cities and regions. This made it hard for the central government to stop cities like Amsterdam from trading. Amsterdam merchants made a lot of money trading arms and ammunition with the American rebels. They exchanged these for colonial goods like tobacco, often through the Dutch colony of St. Eustatius. These merchants also supplied France with `naval stores`, which France needed to build its navy. Britain was blocking France from getting these supplies from other places like Norway.

So, the Dutch Republic, as a neutral country, was very helpful to France's war efforts. Britain, of course, was not happy about this. They tried to convince the Dutch government to stop this trade, but diplomatic talks failed. The Dutch refused to lend their mercenary Scottish Brigade to Britain for service in America. They also (reluctantly) gave shelter to the American `privateer` (a private ship authorized to attack enemy shipping) John Paul Jones in 1779. They also refused to stop exporting arms and ammunition.

These refusals happened because of the influence of Amsterdam and pressure from France's ambassador. When diplomacy didn't work, the British Royal Navy started seizing what they considered `contraband` from Dutch ships on the open sea more often. This caused many protests from the affected merchants. At first, the Dutch government ignored these protests.

Then, France started putting pressure on the Dutch government. They threatened to stop trading with Dutch cities that supported the stadtholder's opposition to taking action against the seizures. This soon convinced those cities to agree with Amsterdam. They started demanding that Dutch naval ships protect their merchant convoys.

The States General of the Netherlands (the Dutch governing body) changed its mind in November 1779. They ordered the stadtholder, as commander-in-chief of the Dutch armed forces, to start offering `limited convoy services` to Dutch shipping. This was despite the fact that the Dutch navy was much weaker than it used to be due to long neglect. The 20 older ships they had were no match for the larger British Royal Navy ships.

According to a Dutch historian, the Royal Navy had 137 `ships of the line` (large warships) at the time, while France had 68. The States-General had decided to build 24 new ships of the line in 1778, but this plan was very slow. This was mainly because only one province, Holland, paid its share of the cost. None of the new ships were ready yet. This situation did not look good for a future naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and Great Britain. It might explain why the Dutch navy was not eager to fight.

Even though the Dutch Republic did not agree with Britain that `naval stores` were contraband, the stadtholder insisted on keeping such items out of the convoys. This was to reduce problems with the British.

The Incident Itself

When the first convoys were prepared in December 1779, the stadtholder gave clear instructions. One convoy was going to the West Indies under Rear-Admiral Willem Crul. Another was going to France and the Mediterranean under Rear-Admiral Count Lodewijk van Bylandt. The stadtholder told them to exclude ships carrying `naval stores` (which he understood as ship timber). He also said not to allow ships from "nations not recognized by the Republic" (like those of John Paul Jones) to join the convoys. Finally, he told Bylandt to avoid anything that could risk the Dutch Republic's neutrality.

Admiral Bylandt's group of ships left the Texel on December 27, 1779. It included his `flagship` (the ship carrying the commander's flag), the 54-gun `ship of the line` Prinses Royal Frederika Sophia Maria. It also had the 40-gun Argo, the 44-gun Zwieten, the 26-gun Valk, and the 26-gun Alarm. They were protecting 17 Dutch merchant ships.

After sailing calmly for a few days through the English Channel, the convoy met a British group of ships on the morning of December 30. This British group included the 90-gun HMS Namur, which was Commodore Fielding's flagship. It also had the 74-gun ships HMS Courageux, HMS Centaur, HMS Thunderer, and HMS Valiant. Other ships included the 60-gun HMS Buffalo, the 50-gun HMS Portland, the 32-gun HMS Emerald, the 20-gun ships HMS Seaford and HMS Camel, the 12-gun HMS Hawk, and the 8-gun HMS Wolf.

The Courageux hailed the Dutch flagship and asked for a `parley` (a discussion). Bylandt agreed. Fielding then sent a boat with two `parlimentaires` (people sent to talk), one of whom was his `flag captain` (the captain of his flagship). This captain demanded that Bylandt allow the British to physically inspect the Dutch merchant ships.

Bylandt replied that this request was unusual. In peacetime, people usually trusted the word of naval escorts that a convoy did not carry contraband. He showed the lists of goods for the ships and sworn statements from the merchant captains that they were not carrying contraband. He added that he had personally checked that the convoy did not have ship timber, even though the Dutch did not consider this contraband.

Marshall asked if the ships carried `hemp` or `iron` (he seemed to know what was on board). Bylandt admitted they did and said these had never been considered contraband. Marshall replied that, according to his new orders, these items were now contraband. Seeing that Marshall would not change his mind, Bylandt sent his own flag captain, his nephew Frederik Sigismond van Bylandt, to the Namur to talk directly with Fielding. This also failed to reach an agreement. Fielding announced he would start searching the Dutch ships the next morning (as night had fallen). The younger Bylandt replied that if that happened, the Dutch would open fire.

During the night, twelve of the Dutch merchant ships managed to slip away. So, the next morning, the convoy only had five ships left. Fielding moved closer with three of his `ships of the line` (Namur and two 74-gun ships). But Bylandt blocked them with Prinses Royal, Argo, and the frigate Alarm (the other two Dutch ships were too far away).

Even so, Namur sent a small boat to one of the Dutch merchant ships. The Prinses Royal then fired two shots across its bow to make it turn away. What happened next is told differently by the British and Dutch. According to Bylandt and his captains, who gave sworn statements during his `court martial` (a military trial), the three British ships immediately fired a `broadside` (all guns on one side of the ship firing at once). The Dutch ships replied with one broadside of their own. According to Fielding, he fired a single shot, which was answered by a broadside, and then the British fired their broadsides.

After this exchange of fire, Bylandt immediately `struck his colours` and signaled the other Dutch ships to do the same. This was surprising, as Dutch rules clearly said that Dutch ships should not surrender if they could still fight, even if the flagship surrendered. It came out at Bylandt's court martial that he had given secret orders to his captains before leaving the Texel. These orders told them to surrender if he gave a specific signal. He later explained that he wrote these secret orders because he knew he would face a much stronger enemy. He decided to offer only a `token resistance` (a small, symbolic fight), just enough to "satisfy honour." But he felt it was important to stop his captains from being too aggressive, as that would prevent his goal of avoiding a pointless conflict.

This was a typical example of warfare in the 1700s, which often tried to avoid unnecessary deaths more than modern warfare. The British understood that striking the colours meant stopping the fight, not a full surrender. They did not try to board the Dutch warships. Fielding continued to inspect the five merchant ships. He then arrested them when he found the contraband, which was bales of `hemp` hidden in the cargo hold.

He then sent a message to Bylandt, allowing him to raise his flags again and continue his journey. However, Bylandt replied that he would stay with the merchant ships. Fielding then demanded that the Dutch warships salute the White Ensign (the British naval flag), as he was allowed to under the treaties between Britain and the Netherlands. Normally, the Dutch did not object to this. But in this case, Bylandt hesitated. However, to avoid starting a fight where his fleet was outmatched, and because he wanted to follow the treaties carefully, Bylandt agreed to this demand. Dutch public opinion would later criticize him for this.

Finally, the British sailed with their captured ships to Portsmouth. Bylandt followed them into port. As soon as he arrived, he sent a complaint to the Dutch ambassador in Britain.

What Happened Next

Many people in the Netherlands were very angry. They were upset by the inspection and by what they saw as Bylandt's `pusillanimity` (lack of courage). Many thought it was `cowardice` or even `treason` (betraying his country). To defend his honour, Bylandt demanded a `court martial` to clear his name. This special group of seven admirals quickly found him innocent of all charges. However, the prosecutor's statement sounded more like a defense than a prosecution. This made many people at the time feel that it was a `whitewash` (an attempt to hide mistakes or wrongdoing). Many even suspected that Bylandt's actions were part of a secret plan by the stadtholder to avoid helping the Americans.

Because of the public anger, the stadtholder had to stop resisting `unlimited convoy` (allowing all ships to be protected). The Dutch would now try to defend their full treaty rights, which pleased France. France then stopped its economic penalties against the Dutch.

On the other hand, the British stopped pretending to respect those treaty rights. In April 1780, the British canceled the Commercial Treaty of 1668. They announced that they would now treat the Dutch like any other neutral country in the conflict. They would no longer grant the Dutch the "free ship, free goods" rights they had before.

Meanwhile, Empress Catherine II of Russia was shocked by this incident and an even more serious one involving Spanish merchant ships and two Russian warships. She decided to issue a statement demanding that all warring countries respect the "free ship, free goods" rule for all neutral nations. France and Spain quickly agreed (Spain even apologized). But the British government hesitated because the declaration was mainly aimed at their navy. Catherine then started talking with other neutral powers, including the Dutch Republic. This led to the formation of the (First) League of Armed Neutrality.

The Dutch Republic saw this as a chance to protect its trade from the Royal Navy without having to join the war against Great Britain. However, the Dutch asked for too much. They wanted the other members of the League to guarantee the safety of their colonies. Catherine was not willing to grant this. Eventually, the Dutch accepted what was offered and joined the League in December 1780.

The British then countered this move by declaring war on the Dutch. They said it was because of the Dutch's secret support for the American rebels. This gave the other members of the League an excuse not to give armed help to the Dutch. The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War had begun.

Images for kids

-

The British flagship, HMS Namur, during the Battle of Lagos in 1759

See Also

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |