Afroasiatic languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Afroasiatic |

|

|---|---|

| Hamito-Semitic, Semito-Hamitic, Afrasian | |

| Geographic distribution: |

North Africa, West Asia, Horn of Africa, Sahel, and Malta |

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language: | Proto-Afroasiatic |

| Subdivisions: |

Omotic

|

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | afa |

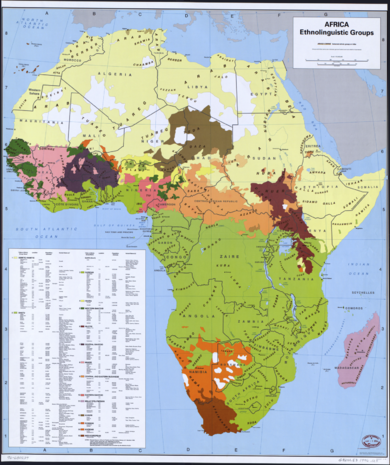

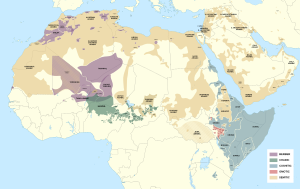

Distribution of the Afroasiatic languages

|

|

The Afroasiatic languages are a large group of about 400 languages. They are spoken by over 500 million people! You can find them mainly in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of the Sahara and Sahel regions. This makes Afroasiatic the fourth-largest language family in the world.

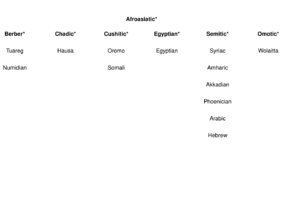

Most experts divide this family into six main branches: Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian, Semitic, and Omotic. Most Afroasiatic languages started in Africa. Only the Semitic branch has many languages that began outside of Africa.

Arabic is the most widely spoken language in this family. It has about 300 million native speakers, mostly in the Middle East and North Africa. Other big Afroasiatic languages include Hausa language (over 34 million speakers), Amharic language (25 million), and Somali language (15 million). Many older Afroasiatic languages, like Ancient Egyptian and some Semitic languages such as Akkadian and Biblical Hebrew, are no longer spoken today.

Scientists who study languages don't fully agree on where or when the very first Afroasiatic language, called Proto-Afroasiatic, was spoken. However, most think it was somewhere in northeastern Africa. Some also suggest it might have been in the Levant (a region in the Middle East). The timeline for Proto-Afroasiatic ranges from 18,000 BC to 8,000 BC. Even the most recent date makes it the oldest language family that linguists agree on today!

It's tricky to study Afroasiatic languages because some branches, like Semitic and Egyptian, have very old written records (from 4,000 BC). But other branches, like Berber, Cushitic, and Omotic, weren't written down until much later, often in the 1800s or 1900s. Even so, these languages share many common features, like similar pronouns and ways to form words.

Contents

Understanding the Name "Afroasiatic"

Why the Name Changed

The most common names for this language family today are Afroasiatic or Afro-Asiatic. You might also hear older names like Hamito-Semitic or Semito-Hamitic.

The name Hamito-Semitic was first used in 1876. It came from the names of two sons of Noah from the Bible: Shem (for "Semitic") and Ham (for "Hamitic"). The idea was that these sons were the ancestors of different groups of people and their languages. For example, the Jews and Assyrians were linked to Shem, while the Egyptians and Cushites were linked to Ham.

However, this biblical family tree doesn't really match how languages actually developed. For instance, the Canaanites were linked to Ham, but their language, Hebrew, is a Semitic language.

Problems with "Hamito-Semitic"

Over time, many linguists stopped using the term Hamito-Semitic. One big reason is that the "Hamitic" part wrongly suggested there was a single "Hamitic" language group that was separate from Semitic. In reality, the languages once called "Hamitic" are now known to be part of different branches within the Afroasiatic family.

Also, the term "Hamitic" became linked to outdated ideas about race. Some scholars used it to suggest that certain African groups were superior because they were supposedly linked to "Caucasians" who migrated into Africa. This idea, called the "Hamitic theory," was later proven wrong by linguists like Joseph Greenberg in the 1940s. He showed that these classifications were based on racial ideas, not true language connections.

The Name "Afroasiatic" Today

The name "Afroasiatic" became popular in 1960, though it was first used in 1914. This name simply refers to the fact that it's the only major language family with many speakers in both Africa and Asia. It's a more accurate and neutral name for this diverse group of languages.

Where Afroasiatic Languages Are Spoken

Experts usually agree that Afroasiatic has six main branches. These are Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian, Semitic, and Omotic. Some scholars even call Afroasiatic a "linguistic phylum" instead of just a "language family" because the relationships between its branches are so old and distant.

There are about 400 languages in the Afroasiatic family. The exact number can change depending on whether a language is considered a separate language or a dialect of another.

Berber Languages

The Berber languages are spoken by about 16 million people today. They are found across North Africa. In the past, they were spoken much more widely, but Arabic has replaced them in many areas since the 600s AD.

Some older languages, like Numidian language (from around 200 BC) and Guanche language (spoken on the Canary Islands until the 1600s AD), might be related to modern Berber languages.

Chadic Languages

Chadic is the largest branch of Afroasiatic, with about 150 to 190 languages. Most Chadic languages are found around the Chad basin. The biggest Chadic language is Hausa, with many native speakers and millions more who use it as a common language in Northern Nigeria. Only about 40 Chadic languages have been fully studied by linguists.

Cushitic Languages

There are about 30 Cushitic languages, spoken in the Horn of Africa and parts of Sudan and Tanzania. The Cushitic family includes languages like Beja language (around 3 million speakers) and Oromo, which has over 25 million speakers. Other languages with over a million speakers include Somali and Afar. Many Cushitic languages have fewer speakers and might be in danger of disappearing.

Egyptian Language

The Egyptian branch has only one language: Egyptian, also known as "Ancient Egyptian." It was spoken in the lower Nile Valley. Egyptian has the longest written history of any language in the world, from around 3000 BCE until 1300 CE.

Ancient Egyptian was written using hieroglyphs, which only showed consonants. Later, a form called Coptic was written using an alphabet that showed vowels. Coptic is no longer spoken every day, but it is still used in the Coptic Orthodox Church. Arabic replaced Egyptian as the main spoken language in Egypt.

Omotic Languages

There are about 30 Omotic languages, mostly spoken in southwest Ethiopia. Many of them haven't been fully studied yet. The two Omotic languages with the most speakers are Wolaitta and Gamo-Gofa-Dawro, each with about 1.2 million speakers.

Most experts agree that Omotic is its own separate branch of Afroasiatic. It used to be considered part of the Cushitic branch.

Semitic Languages

The Semitic family has between 40 and 80 languages. Today, Semitic languages are spoken across North Africa, West Asia, and the Horn of Africa, and even on the island of Malta. This makes them the only Afroasiatic branch with languages that started outside Africa.

Arabic is the most widely spoken Semitic language, with about 300 million native speakers. Amharic from Ethiopia has around 25 million. The oldest written Semitic languages date back to around 3000 BCE.

Where Did Afroasiatic Languages Come From?

When Did Proto-Afroasiatic Exist?

There's no full agreement on exactly when Proto-Afroasiatic was spoken. The latest it could have existed is around 4000 BCE, because Egyptian and Semitic languages are clearly recorded after that. However, these languages likely started to split off much earlier. Estimates range from 18,000 BCE to 8,000 BCE. Even the most recent date makes Afroasiatic the oldest proven language family.

Where Did It Start?

Linguists also don't agree on where Proto-Afroasiatic began. Some suggest locations across Africa, while others point to West Asia. This debate can be a bit heated, with some linking an Asian origin to ideas of "high civilization."

Many scholars believe it started somewhere in Africa. They often suggest a central location like the southeastern Sahara or the nearby Horn of Africa. This idea is supported because the African branches of Afroasiatic are very diverse, while Semitic languages are quite similar to each other, suggesting Semitic spread quickly out of Africa. Those who support an African origin think the language was spoken by hunter-gatherers, as there are no words related to farming in the reconstructed Proto-Afroasiatic vocabulary.

However, a smaller group of scholars believes it started in Asia, specifically the Levant. They argue that Proto-Afroasiatic was spoken by early farmers and then spread to Africa. They point to words related to farming and animals in the reconstructed language.

Sounds and Structure of Afroasiatic Languages

Afroasiatic languages share some interesting features in their sounds and how they build words.

Consonant Sounds

Many Afroasiatic languages have a lot of different consonant sounds. They often have special sounds called "emphatic" consonants, which are made deeper in the throat. You'll also find sounds like "pharyngeal fricatives" (like the 'h' sound in Arabic 'Allah').

Tones

Many Afroasiatic languages use tones. This means the pitch of your voice when you say a word can change its meaning or its grammatical function. For example, saying a word with a high pitch might mean one thing, while saying it with a low pitch means something else. This is common in Omotic, Chadic, and Cushitic languages, but not in Berber or Semitic.

| Language | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Somali (Cushitic) | díbi bull (when it's the subject) | dibi bull (when it's the object) | dibí bull (when it shows possession) |

| ínan, boy | inán girl | ||

| Bench (Omotic) | k'áyts' work! do it! (active command) | k'àyts' be done! (passive command) | |

| Hausa (Chadic) | màatáa woman, wife | máatáa women, wives | |

| dáfàa to cook (to do the action) | dàfáa cook! (a command) | ||

Word Building with Roots

A very common feature in Afroasiatic languages, especially Semitic, is using a "root" made of consonants. Vowels are then added around these consonants to create different words or forms of a verb. For example, in Arabic, the root k-t-b means "write." You can add vowels to make kataba (he wrote), yaktubu (he writes), or kitāb (book).

Most Semitic verbs have three consonants in their root. Many Chadic, Omotic, and Cushitic verbs have two.

| Language | Akkadian (Semitic) | Berber | Beja (Cushitic) | Ron/Daffo (Chadic) | Coptic (Egyptian) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root (meaning) | p-r-s (to divide) | k-n-f (to roast) | d-b-l (to gather) | m-(w)-t (to die) | k-t (to build) |

| Examples | iprus- (he divided) | ǎknəf (he roasted) | -dbil- (he gathered) | mot (he died) | kôt (to build) |

| iparras- (he divides) | əknǎf (he has roasted) | -i:-dbil- (he gathers) | mwaát (he is dying) | kêt (being built) | |

| iptaras (he has divided) | əkǎnnǎf (he roasts) | i:-dbil- (he should gather) | |||

| əknəf (he did not roast) | da:n-bi:l (he gathers, singular) | ||||

| əkənnəf (he is not roasting) | -e:-dbil- (they gather, plural) | ||||

| -dabi:l- (not gathering) |

Word Order

It's not clear what the original word order was for Proto-Afroasiatic. Some branches, like Berber, Egyptian, and most Semitic languages, put the verb first (Verb-Subject-Object). Others, like Cushitic, Omotic, and some Semitic languages, put the verb at the end (Subject-Object-Verb).

Repeating Sounds (Reduplication)

Afroasiatic languages often repeat parts of words or whole words. This is called reduplication. It's used to make new nouns, verbs, adjectives, or adverbs. For example, repeating a verb might show that an action happens many times.

Nouns in Afroasiatic Languages

Gender and Number

Most Afroasiatic languages have grammatical gender, meaning nouns are either masculine or feminine. This system likely comes from Proto-Afroasiatic. Often, a feminine noun is marked with a -t sound at the end.

| Kabyle (Berber) | Hausa (Chadic) | Beja (Cushitic) | Egyptian | Arabic (Semitic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wəl-t 'daughter' | yārinyà-r̃ 'the girl' (r̃ comes from -t) | ʔo:(r)-t 'a daughter' t-ʔo:r 'the daughter' |

zꜣ-t 'daughter' | bin-t 'daughter' |

Afroasiatic languages have many ways to make nouns plural. Sometimes, the noun's gender can even change from singular to plural! Besides adding endings, some languages change the vowels inside the word to make it plural. This is called a "broken plural" and is common in Semitic, Berber, Cushitic, and Chadic.

| Language | Meaning | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ge'ez (Semitic) | king | nɨgus | nägäs-t |

| Teshelhiyt (Berber) | country | ta-mazir-t | ti-mizar |

| Afar (Cushitic) | body | galab | galo:b-a |

| Hausa (Chadic) | stream | gulbi | gulà:be: |

| Mubi (Chadic) | eye | irin | aràn |

Noun Cases

Some Afroasiatic languages use noun cases. This means the ending of a noun changes depending on its role in the sentence (like subject, object, or showing possession). For example, the subject of a sentence might end in -u or -i, while the object ends in -a. Cases are found in Semitic, Berber, Cushitic, and Omotic, but not in Chadic or Egyptian.

| Case | Oromo (Cushitic) | Berber | Akkadian (Semitic) | Wolaitta (Omotic) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| Subject | nam-(n)i boy | intal-t-i girl | u-frux boy | t-frux-t girl | šarr-u-m king | šarr-at-u-m queen | keett-i house | macci-yo woman |

| Object | nam-a | intal-a | a-frux | t-a-frux-t | šarr-a-m | šarr-at-a-m | keett-a | macci-ya |

Verbs in Afroasiatic Languages

Prefixes and Suffixes

Many Afroasiatic languages use prefixes (added to the beginning of a word) or suffixes (added to the end) to change the meaning of verbs. For example, a prefix like *s- can make a verb mean "to cause something to happen" (like make live). A prefix like *t- can make a verb mean "to do something to oneself" (like agree with one another).

| Language | "To cause" (s-) | "To do to oneself" (t-) | "To be done" (n-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akkadian (Semitic) | u-š-apris 'make cut' | mi-t-gurum 'agree (with one another)' | i-p-paris (> *i-n-paris) 'be cut' |

| Figuig (Berber) | ssu-fəɣ 'let out' | i-ttə-ska 'it has been built' | mmu-bḍa 'divide oneself' |

| Beja (Cushitic) | s-dabil 'make gather' | t-dabil 'be gathered' | m-dabaal 'gather each other' |

| Egyptian | s-ꜥnḫ 'make live' | pr-tj 'is sent forth' | n-hp 'escape' |

Noun Derivation with M-prefix

A common way to make nouns from verbs in Afroasiatic languages is by adding an m- prefix. This can create nouns for the person doing the action, the place where the action happens, or the tool used for the action.

| Language | Root (meaning) | Person/Tool | Place/Idea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian | swr (to drink) | m-swr 'drinking bowl' | – |

| Arabic (Semitic) | k-t-b (to write) | mu-katib-un 'writer' | ma-ktab-un 'school' |

| Hausa (Chadic) | hayf- (to give birth) | má-hàif-íi 'father' | má-háif-áa 'birthplace' |

| Beja (Cushitic) | firi (to give birth) | – | mi-frey 'birth' |

| Tuareg (Berber) | äks (to eat) | em-äks 'eater' | – |

Pronouns

The words for pronouns (like "I," "you," "he," "she") are very similar across most Afroasiatic languages (except Omotic). This makes them a key tool for showing that these languages are related.

A common feature is having "independent" pronouns (like "I" in "I am here") and "dependent" pronouns (like "-my" in "my book"). In most branches, first-person pronouns (I, we) have an 'n' or 'm' sound. Third-person pronouns (he, she, they) often have an 's' or 'sh' sound.

| Meaning | North Omotic (Yemsa) | Beja Cushitic (Baniamer) | East Cushitic (Somali) | West Chadic (Hausa) | East Chadic (Mubi) | Egyptian | East Semitic (Akkadian) | West Semitic (Arabic) | Berber (Tashelhiyt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'I' (independent) | tá | aní | aní-ga | ni: | ndé | jnk | ana:ku | ʔana | nkki |

| 'me, my' (dependent) | -ná- -tá- |

-u: | -ʔe | na | ní | -j wj |

-i: -ya |

-i: -ni: |

-i |

| 'we' (independent) | ìnno | hinín | anná-ga inná-ga |

mu: | ána éné |

jnn | ni:nu: | naħnu | nkkwni |

| 'you' (masc. sing. ind.) | né | barú:k | adí-ga | kai | kám | nt-k | at-ta | ʔan-ta | kiji |

| 'you' (fem. sing. ind.) | batú:k | ke: | kín | nt-ṯ | at-ti | ʔan-ti | kmmi (f) | ||

| 'you' (masc. sing., dep.) | -né- | -ú:k(a) | ku | ka | ká | -k | -ka | -ka | -k |

| 'you' (fem. sing., dep.) | -ú:k(i) | ku | ki | kí | -ṯ | -ki | -ki | -m | |

| 'you' (plural, dep.) | -nitì- | -ú:kna | idin | ku | ká(n) | -ṯn | -kunu (m) -kina (f) |

-kum (m) -kunna (f) |

-un (m) -un-t (f) |

| 'he' (independent) | bár | barú:s | isá-ga | ši: | ár | nt-f | šu | – | ntta (m) |

| 'she' (independent) | batú:s | ijá-ga | ita | tír | nt-s | ši | hiya | ntta-t | |

| 'he' (dependent) | -bá- | -ūs | – | ši | à | -f sw |

-šu | -hu | -s |

| 'she' (dependent) | ta | dì | -s sy |

-ša | -ha: |

Numbers

Unlike some other language families, the numbers in Afroasiatic languages don't all come from one original system. This makes it hard to trace them back to Proto-Afroasiatic. Also, many languages have borrowed numbers from other languages. For example, some Berber languages use Arabic words for higher numbers.

| Meaning | Egyptian | Tuareg (Berber) | Akkadian (East Semitic) | Arabic (West Semitic) | Beja (North Cushitic) | West Central Oromo (Cushitic) | Lele (East Chadic) | Gidar (Central Chadic) | Bench (North Omotic) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | m. | wꜥ | yiwən, yan, iğ | ištēn | wāḥid | gáal | tokko | pínà | tákà | mat' |

| f. | wꜥ.t | yiwət, išt | ištiāt | wāḥida | gáat | |||||

| Two | m. | sn.wj | sin, sən | šinā | ʔiṯnāni | máloob | lama | sò | súlà | nam |

| f. | sn.tj | snat, sənt | šittā | ʔiṯnatāni | máloot | |||||

| Three | m. | ḫmt.w | ḵraḍ, šaṛḍ | šalāšat | ṯalāṯa | mháy | sadii | súbù | hókù | kaz |

| f. | ḫmt.t | ḵraṭt, šaṛṭ | šalāš | ṯalāṯ | mháyt | |||||

| Four | m. | (j)fd.w | kkuẓ | erbet(t) | ʔarbaʕa | faḍíg | afur | pórìn | póɗó | od |

| f. | (j)fd.t | kkuẓt | erba | ʔarbaʕ | faḍígt | |||||

| Five | m. | dj.w | səmmus, afus | ḫamšat | ḫamsa | áy | šani | bày | ɬé | ut͡ʃ |

| f. | dj.t | səmmust | ḫamiš | ḫams | áyt | |||||

| Six | m | sjs.w | sḍis | šiššet | sitta | aságwir | jaha | ménéŋ | ɬré | sapm |

| f. | sjs.t | sḍist | šiš(š) | sitt | asagwitt | |||||

| Seven | m | sfḫ.w | sa | sebet(t) | sabʕa | asarámaab | tolba | mátàlíŋ | bùhúl | napm |

| f. | sfḫ.t | sat | seba | sabʕ | asarámaat | |||||

| Eight | m. | ḫmn.w | tam | samānat | ṯamāniya | asúmhay | saddet | jurgù | dòdòpórò | nyartn |

| f. | ḫmn.t | tamt | samānē | ṯamānin | asúmhayt | |||||

| Nine | m. | psḏ.w | tẓa | tišīt | tisʕa | aššaḍíg | sagal | célà | váyták | irstn |

| f. | psḏ.t | tẓat | tiše | tisʕ | aššaḍígt | |||||

| Ten | m. | mḏ.w | mraw | ešeret | ʕašara | támin | kuḍan | gòrò | kláù | tam |

| f. | mḏ.t | mrawt | ešer | ʕašr | támint | |||||

Similar Words (Cognates)

Afroasiatic languages share some words that come from the same original Proto-Afroasiatic word. These are called cognates. It can be hard to find them because the languages have changed so much over thousands of years. Also, languages often borrow words from each other, which can make it tricky to tell if a word is truly a cognate or a loan.

However, linguists have found some words that are clearly related across different branches. These often have simple sound changes that connect them.

| Meaning | Proto-Afroasiatic (original form) | Omotic | Cushitic | Chadic | Egyptian | Semitic | Berber | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to strike, to squeeze | – | *bak- | Gamo bak- 'strike' | Afar bak | Wandala bak 'to strike, beat'; Hausa bùgaː 'to hit, strike' | bk 'kill (with a sword)' | Arabic bkk 'to squeeze, tear' | Tuareg bakkat 'to strike, pound' |

| blood | *dîm- *dâm- |

*dam- | Kaffa damo 'blood'; Aari zomʔi 'to blood' |

(cf. Oromo di:ma 'red') | Bolewa dom | (cf. jdmj 'red linen') | Akkadian damu 'blood' | Ghadames dəmmm-ən 'blood' |

| to die | *maaw- | *mawut- | – | Rendille amut 'to die, to be ill' | Hausa mutu 'to die', Mubi ma:t 'to die' |

mwt 'to die' | Hebrew mwt, 'to die' Ge'ez mo:ta 'to die' |

Kabyle ammat 'to die' |

| tongue | *lis'- 'to lick' | *les- 'tongue' | Kaffa mi-laso 'tongue' | – | Mwaghavul liis tongue, Gisiga eles 'tongue'; Hausa halshe(háɽ.ʃè) 'tongue'; lashe 'to lick' |

ns 'tongue' | Akkadian liša:nu 'tongue' | Kabyle iləs 'tongue' |

| to spit | *tuf- | *tuf- | – | Beja tuf 'to spit'; Kemant təff y- 'to spit'; Somali tuf 'to spit' |

Hausa tu:fa 'to spit' | tf 'to spit' | Aramaic tpp 'to spit'; Arabic tff 'to spit' |

– |

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas afroasiáticas para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas afroasiáticas para niños

- Afroasiatic phonetic notation

- Borean languages

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of Asia

- Nostratic languages

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |