Aircraft of the Battle of Britain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Aircraft of the Battle of Britain |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| R4118 flew 49 missions during the Battle of Britain. It's the only Battle of Britain Hurricane still flying today. |

The Battle of Britain was a huge air fight that happened in the summer and autumn of 1940. The German Air Force, called the Luftwaffe, tried to take control of the skies over the United Kingdom. Their goal was to make it easier for Germany to invade Britain.

The German leader, Adolf Hitler, and his military commanders believed they couldn't invade Britain successfully until the British Royal Air Force (RAF) was defeated. They also wanted to destroy factories that made aircraft, attack important political places, and scare the British people into giving up.

The British say the battle lasted from 10 July to 31 October 1940. This was when the most intense daytime bombing happened. German historians often say the battle started in mid-August 1940 and ended in May 1941. This was when German bombers left to prepare for their attack on the Soviet Union.

The Battle of Britain was the first major battle fought entirely by air forces. The British mainly used fighter planes to defend themselves. The Germans used a mix of bombers and fighter planes to protect them. It was the biggest bombing campaign ever attempted at that time. Germany's failure to destroy Britain's air defenses or break British spirits was seen as their first major defeat in World War II.

Fighter Aircraft in the Battle of Britain

Main Fighters: Hurricane, Spitfire, and Bf 109

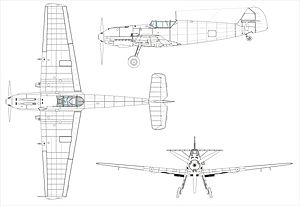

The most famous fighter planes in the Battle of Britain were the British Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire Mk I. The German Messerschmitt Bf 109 E variant (called Emil) was also a key single-engine fighter.

Even though the Spitfire got more attention, the Hurricanes were more common. They were responsible for most of the German planes shot down, especially early in the battle. The Hurricane could be refueled and re-armed in just 9 minutes, while the Spitfire took 26 minutes. This made the Hurricane very effective.

Many Spitfires were bought by people, towns, or companies. They would raise £5,000 to buy a Spitfire and could even name it. For example, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands donated enough money to buy 43 Spitfires!

The Spitfire and Bf 109E were very similar in speed and how easily they could move. Both were a bit faster than the Hurricane. However, the Hurricane was slightly larger and easier to fly. It was very good at fighting Luftwaffe bombers. The Royal Air Force (RAF) usually sent Hurricanes to attack bomber groups. They used Spitfires to fight the enemy's fighter escorts.

The Spitfire's cockpit gave a good view upwards, but the curved front window could make things look blurry. This made it hard to spot enemy planes far away. The Hurricane had a higher seat, giving its pilot a better view over the nose. Later versions of the Bf 109 also improved their cockpit visibility.

How They Flew

Each of the three main fighters had its own strengths and weaknesses in how it handled. Most air combat happened at about 20,000 feet or lower.

If a Spitfire pilot pulled the stick back too hard in a tight turn, the plane could stall. This would cause a strong shudder and clattering noise. It would also make the plane roll sideways. This noise was a warning to the pilot to ease up on the turn.

The Bf 109 had a gentle stall and good control even under high "g-forces." This allowed German pilots to push the plane to its limits in dogfights. The Bf 109 also had special slats on its wings that opened automatically before stalling. However, these slats could open unevenly during tight turns, making it harder to chase enemy planes.

The British fighters used Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. These engines had a problem: they would cut out if the plane went into a dive that caused negative "g-forces." The Bf 109's engine used direct fuel injection, which meant it didn't have this problem. This gave the Bf 109 pilots an advantage. They could dive away from an enemy without their engine stopping.

In terms of turning, the Spitfire and Hurricane could turn tighter than the Bf 109. The Spitfire's turning circle was estimated to be about 212 meters (700 feet). The Bf 109E's was about 270 meters (890 feet). The Emil (Bf 109E) was smaller than the RAF fighters. It was also harder to land and take off. At high speeds, its controls became very stiff, requiring more strength to maneuver. However, the Bf 109E had the fastest roll rate, meaning it could roll from side to side very quickly.

Overall, the differences between the Bf 109 and Spitfire were small. In combat, who won often depended on who saw the other first, who had the higher altitude, how many planes each side had, and the pilot's skill. The main differences were the Spitfire's tighter turning ability and the Bf 109's faster climb rate.

Weapons

Both British fighters, the Hurricane and Spitfire, had eight .303 Browning machine guns in their wings. These guns were set up so their bullets would meet at a certain distance. The Brownings fired very fast, sending out many bullets in a short burst. While good against many planes, these small bullets often couldn't get through the armor plating on Luftwaffe aircraft. Special incendiary (fire-starting) bullets, called "De Wilde," were more damaging.

Some Spitfires, called Spitfire Mk. IBs, were changed to carry a larger 20 mm cannon in each wing. 19 Squadron used this version in June 1940. When they first used them in August, the cannons often jammed. But when they did work, the Hispano cannon was very powerful. Its shells could easily go through armor and self-sealing fuel tanks.

The Bf 109E's weapons depended on its specific version. The E-1 had four 7.92mm machine guns: two above the engine and two in the wings. The E-3, E-4, and E-7 versions kept the engine machine guns but replaced the wing machine guns with two 20 mm cannons. These cannons fired powerful "mine shells." Even though these explosive shells caused more damage, the cannons had a low firing speed and only 60 rounds per drum. This meant they weren't always better than the RAF's eight machine guns.

Three or four hits from the cannons were usually enough to bring down an enemy fighter. Even if a plane made it back to base, it was often too damaged to be repaired. For example, a new Spitfire was hit by 20 mm shells on 18 August. It landed safely but was too damaged to be fixed.

Fuel Tanks

A problem with the Hurricane was a fuel tank right behind the engine. This tank could catch fire and quickly burn the pilot before they could escape. Later, a fire-resistant material was added to the tank, and an armored panel was placed in front of the instrument panel. The main wing fuel tanks were also vulnerable to bullets from behind.

The Spitfire's main fuel tanks were in the fuselage, in front of the cockpit. They were better protected. The lower tank was self-sealing, meaning it could seal small holes. A 3mm thick aluminum panel covered the top tanks to deflect small bullets. The cockpit was also fireproofed with asbestos.

All German fighters and bombers had self-sealing fuel tanks. While these could seal leaks from most bullets, they couldn't always stop the "De Wilde" incendiary rounds used by the RAF, which could cause fatal damage.

German Fighter Fuel Capacity

A big problem for the German single-engine fighters was the Bf 109E's limited fuel. It could only fly about 660 km (410 miles) on its internal fuel. When they reached a British target, they only had about 10 minutes of fuel left before they had to turn back. This left the bombers without fighter protection.

The Bf 109E-7 version fixed this problem by adding a rack under the plane. This rack could carry a bomb or a 300-liter (80 US gallon) drop tank. This drop tank doubled its range to 1,325 km (820 miles). However, this change wasn't added to older Bf 109Es until October 1940.

Strength and Armor

From mid-1940, the Spitfire had 33 kg (73 pounds) of steel armor. This included protection for the pilot's head and back, and for the glycol header tank. The Hurricane had similar armor. It was considered the toughest and most durable of the three main fighters. Hurricanes were also easier to repair than the more complex Spitfire. The Hurricane had a lot of fabric covering instead of metal skin. This meant that if a bullet hit, it would just pass through, leaving small holes that were easy to patch.

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 E-3 got extra armor in late 1939. More armor was added behind the pilot's head and behind the fuel tank during and after the Battle of France.

Propeller Types

By July 1940, British fighters started using more efficient constant speed propellers. These new propellers, made by de Havilland and Rotol, helped the Merlin engine run more smoothly at all heights. They also made takeoffs and landings shorter. Most RAF fighters had these new propellers by mid-August. The Bf 109E also used a constant speed propeller with automatic pitch control.

100 Octane Aviation Fuel

In 1940, all front-line RAF Fighter Command aircraft started using 100 octane fuel. This was a very powerful type of fuel. With 100 octane fuel, the supercharger of the Merlin III engine could be "boosted" to produce 1,310 horsepower. This greatly improved the plane's climb rate, especially at lower heights. It also increased the top speed by 25–34 mph up to 10,000 feet. This powerful fuel helped British fighters match the performance of the German planes.

Germany mostly made its aviation fuel from coal. At the start of the war, the Luftwaffe used 87 octane fuel. In 1940, they introduced an improved fuel called "C2," which was similar to the Allied 100 octane fuel. This C2 fuel was used in some Bf 109E-4/N and E-7/N aircraft. It increased the engine's power by 20%.

Other Fighter Aircraft

Besides the main three, other fighter planes also took part in the Battle of Britain. Most of these were twin-engined "heavy fighters."

Messerschmitt Bf 110

At the start of the battle, the twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110 was meant to fight other planes while protecting German bombers. It was a well-designed plane, fast and with a good range. However, the idea that it could defend bombers against fast, single-engine fighters was wrong. When fighting Hurricanes and Spitfires, the Bf 110s suffered heavy losses. They were only slightly more maneuverable than the bombers they were supposed to protect.

A version of the Bf 110, the Bf 110D-1, was nicknamed "Dachshund-belly" because of a large, fixed fuel tank under its body. On 15 August, a German unit using these planes attacked North Eastern England. Seven out of 21 Bf 110s were destroyed.

The Bf 110 units had very high casualty rates throughout the battle. They couldn't live up to the high hopes of Hermann Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe.

The Bf 110 was most successful as a "fast bomber." One unit, "Test Group 210," showed it could carry more bombs over a longer distance than a Ju 87. It was also much faster, especially at lower heights, making it better at escaping RAF fighters. The Bf 110 had strong forward-firing weapons: two 20 mm cannons and four 7.92 mm machine guns. It also had one 7.92 mm machine gun for rear defense.

Boulton Paul Defiant

For the British, the Boulton-Paul Defiant was the most disappointing fighter. It was designed to be a "bomber destroyer." The idea was that its four-gun turret would be perfect for attacking bombers from behind. However, the German bombers didn't have tail gunners in the rear fuselage.

By 1940, it was clear that the best planes for fighting bombers were single-engine, single-seat fighters with guns that fired forward. The Defiant had no forward-firing guns. Also, if the gunner needed to escape the turret in an emergency, it was very difficult.

Only two RAF units used the Defiant during the battle. On 19 July, one squadron lost four Defiants and 10 crew members in a fight with Bf 109s. A month later, another squadron lost four Defiants and seven crew members. Both units were pulled from daytime operations. However, the Defiant was found to be much better as a night fighter. During the winter bombing raids on London in 1940–41, Defiants shot down more enemy planes than any other type at night.

Italian Fighter Aircraft

The Fiat CR.42 Falco was a biplane fighter used by the Italian Air Corps. They only flew one mission during the main battle, escorting bombers on a raid on Ramsgate on 29 October. After the battle, on 11 November 1940, four CR.42s were destroyed by RAF Hurricanes with no losses to the RAF. The German Luftwaffe planes found it hard to fly in formation with the slower biplanes. The CR.42s were also no match for the more modern British fighters, so they were sent back to the Mediterranean.

The Italians also had a few Fiat G.50 Freccia monoplane fighters. Like the Bf 109E, this fighter had a very short range, probably due to limited fuel. Most of these planes also lacked radios, which made them difficult to use effectively.

Other British Fighters

The Bristol Blenheim was used by both bomber and fighter commands. About 200 Mk. I bombers were changed into Mk. IF long-range fighters. By June 1940, daytime Blenheim losses were a concern for Fighter Command. It was decided that the Mk. IF would mainly be used for night fighter duties.

On the night of 18 June 1940, Blenheim night fighters shot down five German bombers over London. This showed they were better suited for night operations. In July, some Blenheims were equipped with Airborne Interception (AI) Mk. III radar. With this radar, a Blenheim achieved the first success on the night of 2/3 July 1940, shooting down a Dornier Do 17 bomber. The Blenheim became very important as a night fighter. Later, the faster and better-armed Bristol Beaufighter gradually replaced it.

The first Beaufighters entered service in early September 1940. They were meant for night fighting. On the night of 19/20 November 1940, a Beaufighter IF with AI radar shot down a Ju 88. This was the first of 20 victories for its pilot, Flt Lt. John Cunningham.

The only British biplane fighter still in service was the Gloster Gladiator. Although it didn't see much combat during the main aerial battles, Gladiators did intercept a He 111 in late October 1940.

The British also had a new cannon-armed fighter coming into service, the twin-engined Westland Whirlwind. However, problems with its engines and slow production meant it didn't enter service until December 1940.

Bomber Aircraft

Most of the bomber aircraft in the Battle of Britain were German. The Italians also used a small number.

German Bomber Aircraft

In 1940, the Luftwaffe mainly used three twin-engined medium bombers: the Dornier Do 17, the Heinkel He 111, and the Junkers Ju 88. Even with advanced bomb sights and navigation tools, hitting small or difficult targets like radar stations was hard.

For very accurate attacks, the Germans used dive bombers like the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. The Junkers Ju 88 could also dive bomb, but it was mainly used for level bombing. The Stuka had been very effective in the Battle of France. However, the Ju 87 was slow and had weak defensive weapons. It couldn't be protected well by fighters because of its low speed. The Stuka needed air superiority to be effective, but that was exactly what was being fought for over Britain. Because of heavy losses, the Stuka was pulled from attacks on Britain in August.

Another problem for German bombers was their light defensive weapons. At the start of the battle, they usually had only three hand-held machine guns. These guns had small magazines that emptied quickly. This was not enough against concentrated attacks from Hurricanes and Spitfires. Even if a German gunner hit a fast fighter, the damage was often not enough to stop the attack. Efforts were made to add more defensive weapons, but this meant more crew members or overworked existing crew. This problem was never fully solved, and German bombers had to rely on their fighters for protection.

The bombers did have some advantages. More armor was added to important areas, making the crew safer. Their fuel tanks were also well protected by layers of self-sealing rubber. However, incendiary bullets from RAF fighters could sometimes ignite fuel vapor in empty tanks.

The He 111 was almost 100 mph slower than the Spitfire, making it easy to catch. However, its heavy armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and improved defensive weapons made it hard to shoot down. It was the most common German bomber during the battle. It could carry 2000 kg (4,400 lbs) of bombs inside. Later versions could carry even more bombs on external racks. The He 111's bomb sight allowed for good accuracy for a level bomber.

The Do 17Z was an older German bomber, no longer being made by the start of the battle. It was known as "the flying pencil" because of its slim shape. Its air-cooled engines meant it could often survive fighter attacks because it didn't have a vulnerable cooling system. The Dornier was also easy to maneuver. Its main problem was its limited combat range of 200 miles when fully loaded. Its bomb capacity was also limited to 2,205 lbs.

Of the four types of bombers used by the Luftwaffe, the Ju 88 was considered the hardest to shoot down. It was quite maneuverable as a bomber. Especially at low altitudes with no bombs, it was fast enough that a Spitfire would struggle to catch it. It could carry up to 3,000 kg (6,600 lbs) of bombs. However, only smaller bombs could be carried inside. Larger bombs had to be carried on external racks, which slowed the plane down. The Ju 88 was very versatile. It could do level bombing, dive bombing, or low-level attacks.

Even though the Ju 88 operated in smaller numbers than the Do 17 and He 111, it suffered the highest losses. 313 Ju 88s were lost, compared to 132 Do 17s and 252 He 111s.

A small number of four-engined Focke-Wulf Fw 200 planes, converted from airliners, were used to attack ships and fly long-range reconnaissance missions around Britain and into the Atlantic Ocean.

Italian Bomber Aircraft

The Corpo Aereo Italiano (CAI) was an Italian air force group that joined the very late stages of the Battle of Britain.

Their bomber force included about 70 Fiat BR.20 twin-engined bombers. The BR.20 could carry 1600 kg (3,528 lbs) of bombs.

They also had five CANT Z.1007 planes for reconnaissance and several Caproni Ca.133 transport planes. The Italian bombers flew limited missions towards the end of the battle. They flew about 102 missions, but only one had any real success. On 29 November 1940, a raid caused severe damage to a factory in Lowestoft and killed three people.

Their first mission on 25 October was a night attack on Harwich. Three bombers were lost: one crashed on takeoff, and two got lost on their way back. On 11 November, 10 BR.20s, escorted by Fiat CR.42 biplane fighters, raided Harwich during the day. RAF Hurricanes intercepted them. Three bombers were shot down, and three CR.42s were destroyed, with no losses to the Hurricanes. In early January 1941, all the Italian bombers were sent to other areas.

Full List of Aircraft

United Kingdom

Only the squadrons listed as Battle of Britain RAF squadrons were counted for the award of a campaign medal.

- Bristol Blenheim

- Blenheim Mk. IF – Fighter Command (night fighter)

- Blenheim Mk IVF – Coastal Command

- Bristol Beaufighter Mk. I – Fighter Command

- Boulton Paul Defiant Mk. I – Fighter Command

- Gloster Gladiator – Fighter Command (limited numbers)

- also Gloster Sea Gladiator (limited numbers, operated by 804 Naval Air Squadron)

- Hawker Hurricane Mk. I and Mk IIA series I – Fighter Command

- Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I and Mk. II – Fighter Command

- Westland Lysander (limited numbers) (Opening days)

- Grumman Martlet Mk. I (limited numbers, operated by 804 Naval Air Squadron late in battle)

- Fairey Fulmar (limited numbers, operated by 808 Naval Air Squadron)

Germany

- Breguet 521 Bizerte

- Dornier Do 17

- Do 17M-1

- Do 17P-1

- Do 17Z-2

- Do 17Z-3

- Dornier Do 18D-1 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Focke-Wulf Fw 200C-3

- Heinkel He 59C-2 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Heinkel He 111

- He 111H-1

- He 111H-2

- He 111H-3

- He 111P-2

- He 111P-4

- Heinkel He 115 B-1 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Heinkel He 115 B-2 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Junkers Ju 87

- Ju 87B-1

- Ju 87B-2

- Junkers Ju 88

- Ju 88A-1

- Ju 88A-5

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Bf 109E-1

- Bf 109E-1B

- Bf 109E-3

- Bf 109E-4

- Bf 109E-4/B

- Bf 109E-4/N

- Bf 109E-4/BN

- Bf 109E-7

- Bf 109E-7/N

- Bf 109F-1

- Messerschmitt Bf 110

- Bf 110C-4

- Bf 110C-4/B

- Bf 110C-5

Italy

- Fiat BR.20M Cicogna

- Fiat CR.42S Falco

- Fiat G.50 Freccia

See also

- Air warfare of World War II

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |