Andrew Sprowle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Andrew Sprowle

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c.1710 Milton, Dunbartonshire, Scotland

|

| Died | 1776 (age 65) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | Merchant, slave trader, naval agent,shipyard owner |

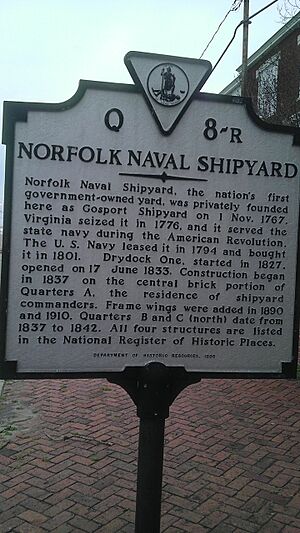

| Known for | founding Gosport Ship Yard (now Norfolk Naval Shipyard) |

Andrew Sprowle (around 1710 – 1776) was an important businessman in Portsmouth, Virginia. He was a merchant, a British naval agent, a Loyalist (someone loyal to Britain during the American Revolution), a landowner, and a shipyard owner. He also owned and traded enslaved people.

Sprowle is best known for starting the Gosport Ship Yard. This shipyard is now called the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. Andrew Sprowle moved from Milton, West Dunbartonshire, Scotland to Virginia in the mid-1700s. He lived there until he died on May 29, 1776.

Contents

- Early Life in Scotland

- Moving to Virginia

- First Marriage

- Owning and Trading Enslaved People

- Privateer Activities

- A Respected Merchant

- Gosport Shipyard

- The Norfolk Anti-Inoculation Riots

- Chairman of the Board of Trade

- Marriage to Katherine Leslie Hunter

- Revolutionary War

- Death

- Deaths in Sprowle's Enslaved Workforce

- Legacy

- See Also

- Images for kids

Early Life in Scotland

Andrew Sprowle was born in 1710 in Milton, Dunbartonshire, Scotland. He was the third son of John Sprowle, who was the Laird (or lord) of Milton. Andrew's father had important jobs for the government. He collected taxes and paid army troops. During the Jacobite revolts (uprisings against the British Crown), Andrew's father stayed loyal to the King.

As a young man, Andrew probably visited Glasgow often. His older brother went to Glasgow University. His father also had business in the port city. Andrew's father died in 1731. His older brother, John Spreull II, inherited the family title and property. This was because of a tradition called primogeniture, where the oldest son inherits everything.

The family name was spelled in many ways during Andrew's life. These spellings included Sproule, Spreulle, Sproul, Sproull, and Sprowle. Andrew himself spelled it "Spreule" and "Sprowle." In this article, we use "Sprowle," as he did in his will.

There is only one short description of Andrew Sprowle's appearance. It was written in 1768 by a merchant named William Nelson. He said Sprowle had white hair and was bald. He wore a silk coat with holes in his stockings. Even so, he looked respectable and was the oldest among the merchants. Nelson said Sprowle gave a good speech to the new colonial Governor, Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt.

In his will from 1774, Andrew Sprowle asked for his portrait to be sent to his sister. He wanted her to take good care of it. The portrait was likely sent to his younger sister Jane, but its location today is unknown.

Moving to Virginia

Like many younger sons, Andrew Sprowle left Scotland to find his fortune. He came to Virginia around 1733, though the exact date is debated. He settled in Norfolk Borough, where he saw chances to become wealthy in the growing town of Portsmouth.

Early records show that by the 1730s, Sprowle worked with Alexander Mackenzie, another Scottish merchant. He later became an independent merchant in the mid-1740s.

Sprowle was well-respected by other merchants. He served for 36 years as the President of the Court of Virginia Merchants. By the 1750s, he was a very successful businessman. However, he never held a local political job like alderman.

In 1746, he was listed as a merchant in Norfolk Borough. In 1752, he bought land in Portsmouth. He kept buying more land, including waterfront areas in Gosport. This land later became part of the Gosport Navy Yard. He was still buying property in Gosport as late as 1772.

In 1763, Portsmouth expanded its boundaries. Andrew Sprowle was named one of the first Town Trustees.

First Marriage

In his 1774 will, Andrew Sprowle wrote that he wanted to be buried in Trinity Church grounds in Portsmouth, Virginia. He wanted to be buried next to "Anabella McNeill, alias Sprowle." He also asked for a tombstone made of Irish marble. This is the only mention found of Sprowle's first wife, Anabella McNeill.

Owning and Trading Enslaved People

Andrew Sprowle is known for starting the Gosport shipyard, which built and fixed ships. However, he also owned many enslaved people and traded them. He also owned ships used in the slave trade.

Thomas McCulloch, Sprowle's business manager, said that Sprowle's enslaved workers were very important to his businesses. These workers had many skills. They included a skipper (boat captain), sailors, a caulker (who sealed ship seams), a cooper (who made barrels), a miller, a mason, a joiner, a painter, a glazier, a sawyer, and planters.

McCulloch also said that Sprowle rented out his enslaved workers for other jobs to earn more money. He noted that many of Sprowle's enslaved sailors died during the war. Enslaved women worked as cooks, laundry maids, seamstresses, and house maids. McCulloch estimated the total value of Sprowle's enslaved workforce at £1200 sterling.

In 1774, Sprowle gave instructions to sell his plantation at Sewells Point, along with his enslaved people. He wanted to sell them when prices were good. Records from the University of Sydney show details of Andrew Sprowle's enslaved workforce.

One of Sprowle's warehouses was used as a market for enslaved people.

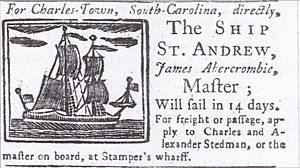

In 1935, a scholar named Elisabeth Donnon found that at least two of Andrew Sprowle's ships, the brigantine Saint Andrew and the sloop Providence, were used in the slave trade between American ports. British records from 1748-1751 confirm Sprowle owned these ships.

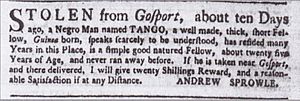

There is also evidence that the St. Andrew, Providence, and a third ship called the Glasgow carried hundreds of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic to the Caribbean in the 1740s and 1750s. One of Sprowle's ships may have brought an African man named "Tango" from Guinea to Portsmouth, Virginia. Tango was later recaptured and mentioned in Sprowle's 1774 will.

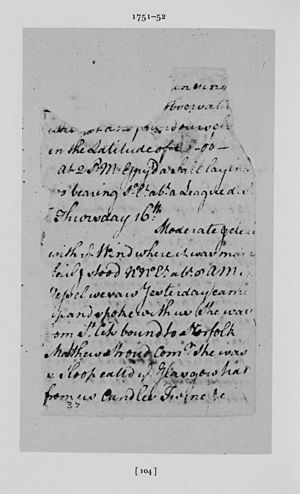

George Washington wrote in his diary in 1751 about a sloop called the Glasgow, owned by Andrew Sprowle. Washington also bought candles from Sprowle's business, "Sprowle & Crooks," in 1771.

Privateer Activities

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), Andrew Sprowle used his shipyard to prepare ships as privateers. Privateers were private ships allowed by the government to attack and capture enemy ships. The Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, Francis Fauquier, gave Sprowle and other merchants permission to do this.

Sprowle was very active in sponsoring privateers. One of his ships reportedly captured a Spanish vessel. Since Spain was not officially at war with Britain, this caused a complaint from the Spanish government. Governor Fauquier was upset by Sprowle's actions. He wrote that Sprowle's behavior was "scandalous." There are no records that Governor Fauquier took further action. However, Sprowle and other privateers made a lot of money by selling the captured goods.

A Respected Merchant

In April 1767, a French traveler visited Andrew Sprowle's new home near Portsmouth, Virginia. He was very impressed with Sprowle's Gosport estate and shipyard. He wrote that Sprowle lived in a pleasant place across a creek from the town. His house was called Gosport. He had a very good wharf where the King's ships often docked. The traveler called Sprowle "a merchant of great repute" (meaning highly respected).

Gosport Shipyard

Sprowle started the Gosport Ship Yard in 1767 under the British flag. He likely based it on shipyards he saw in Scotland. Sprowle was smart to build his new shipyard directly across the Elizabeth River from Portsmouth. He also gave it a good name, "Gosport," which means "God's Port," like a similar place in England.

His shipyard included a large five-story warehouse. It was one of the biggest buildings in North America at the time. This strong stone building was 91 feet long and 41 feet wide. It was worth over £1,000 sterling. Sprowle's shipyard quickly became very important locally.

His business agent, Thomas McCulloch, said that British ships often stayed at Gosport during winter. They used the shipyard for water and repairs. As Sprowle's yard and warehouses grew, it became one of the largest complexes of its kind in the Southern colonies.

The shipyard property also had three other warehouses, an accounting office, a smith's shop, a house, a kitchen, and a large iron crane from London. The shipyard is now known as Norfolk Naval Shipyard. It is the oldest continuously working shipyard for the United States Navy.

The Norfolk Anti-Inoculation Riots

In 1768, many people in the Norfolk area feared smallpox. A group of Scottish merchants, including Andrew Sprowle, wanted to get inoculated (a early form of vaccination). They asked Dr. John Dalgleish to inoculate their families and enslaved people against smallpox.

Rumors spread that a similar effort in Yorktown, Virginia, had caused a smallpox outbreak. This made many citizens scared and suspicious. People worried that inoculation might spread smallpox instead of stopping it. Mobs formed and attacked Dr. Campbell's plantation, where the inoculations were planned. His house was burned down. Those who were inoculated were forced to go to the Norfolk "pest house" (a place for people with infectious diseases).

Dr. Dalgleish was put on trial but was cleared the next year. Inoculation was new but not against the law. However, in June 1770, a law was passed to punish anyone who intentionally spread smallpox.

The smallpox riots in Norfolk left lasting bad feelings. The rioters were never punished. Also, people linked the Scottish merchants, including Sprowle, to spreading disease. Many people who supported the American cause were against inoculation. This led to less trust in the justice system. Some later claimed Sprowle and other Loyalists tried to spread smallpox. After Sprowle's death, a newspaper gloated about his death and linked him to spreading smallpox.

Benjamin Franklin, who supported inoculation, later made similar accusations against the British. He said they tried to spread smallpox by inoculating Black prisoners and letting them escape. While Sprowle supported inoculation, it's unclear if he or his enslaved workers were vaccinated. But the rumors linking him to a smallpox plot continued even after his death.

Chairman of the Board of Trade

In 1769, a group of wealthy merchants met in Williamsburg. They wanted to make business faster and cheaper. They set specific days for their meetings. They also wanted to have an organized voice to talk to the House of Burgesses (the local government) and the Governor. They chose Andrew Sprowle as their leader.

One of their first decisions was to agree not to import tea, glass, or paint into Virginia. This was until the Townshend Acts (taxes from Britain) were removed. Andrew Sprowle was a main signer of this agreement. After signing, the group walked to Raleigh's Tavern. Sprowle and Peyton Randolph led them in toasts to the King and Queen.

Marriage to Katherine Leslie Hunter

Katherine Leslie Hunter was from Glasgow, Scotland. She came to America with her first husband, James Hunter, a merchant. They married in 1754 and had seven children. Katherine knew Andrew Sprowle because James Hunter was Sprowle's nephew.

James Hunter died on October 12, 1774. Katherine married Andrew Sprowle on October 29, 1775, in Gosport. On her wedding day, Katherine wrote to her daughter, also named Katherine, who was at school in Glasgow. She told her to study hard, especially writing and arithmetic. She also reminded her daughter to thank Andrew Sprowle for his kindness.

Like most Scottish merchants in Virginia, Andrew and Katherine Sprowle supported the British Crown. Katherine was well known to Governor Dunmore. She hosted parties at the British barracks in Gosport, where British soldiers and Loyalists mixed.

Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, Andrew Sprowle gave a lot of support to the British Royal Navy. Early in the war, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, occupied Sprowle's Gosport shipyard. Lord Dunmore was a personal friend of Sprowle and a Loyalist. Sprowle hosted Dunmore at his home, making Gosport "virtually the Royal capital of Virginia."

Lord Dunmore declared martial law (military rule) and strengthened his position. On October 29, 1775, Katherine wrote to her daughter that Gosport was the only place holding all the friends of the British government. She said Andrew Sprowle was like a father to everyone, and even the Governor asked for his advice. She joked that she was the "Directress of both the Army & Navy" because she gave out passes.

The Continental Army later drove Lord Dunmore from the area after the Battle of Great Bridge (December 9, 1775). Dunmore's forces were forced onto British ships offshore. Many people on these crowded ships, including Loyalist refugees and former enslaved people, became sick with smallpox and typhus.

Andrew Sprowle was very worried about being called a Loyalist. He said his main goal was "self preservation." In a letter from November 1, 1775, he wrote that "the Virginians" were "all against the Scots men" and threatened to "Exterpate them." Another letter from late 1775 showed his growing fear. He wrote that about 300 British soldiers were in his storehouse at Gosport, able to defend against 1000 Virginia men. He felt safe as long as the soldiers were there.

These letters were intercepted and published. Sprowle's name also appeared in another letter from a Norfolk merchant, Walter Hatton, who told someone to send mail to Sprowle's care.

On November 16, 1775, Lord Dunmore entered Norfolk and made the Scottish merchants swear loyalty to the King. This, along with the intercepted letters, made people even more suspicious of Scottish merchants. It showed that Sprowle and others were loyal to Britain.

Revolutions often force people to choose sides. In the end, Sprowle, like many Loyalists, chose to stay loyal to the British Crown. He didn't want to lose his business ties, his job as a British Naval Agent, or his friendship with Lord Dunmore. After the war, Lord Dunmore confirmed Sprowle's loyalty.

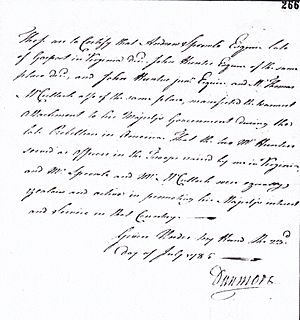

Katherine Sprowle also told the Loyalty Board in 1785 about their loyalty. She said that when Lord Dunmore came to Gosport in 1775, Mr. Sprowle provided houses for British troops and hosted officers. She said she helped the British and never supported the Americans.

Katherine testified that on January 4, 1776, American rebel soldiers burned and destroyed almost every building in Gosport. They also went to his plantation at Sewell's Point, took his enslaved people, drove off his cattle, and burned his barn.

Captain John Balat, a British officer, remembered Andrew Sprowle's strong loyalty. He said Sprowle gave up houses for troops and made their stay comfortable. This made him very unpopular with the Rebels. After the Battle of Great Bridge, Sprowle, despite his age, had to take refuge on a ship. He watched his property burn.

John Hunter Jr., Andrew Sprowle's grandnephew and Katherine's son, was a captain in the Queens Loyal Virginia Regiment. He fought at the Battle of Great Bridge. He said he lived under his uncle's care and was influenced by his family to support the British.

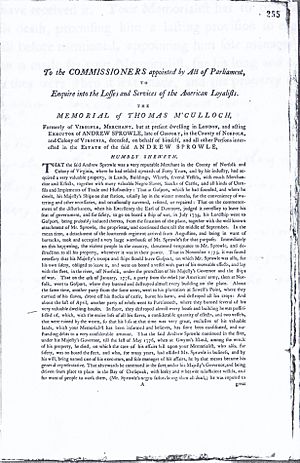

Thomas McCulloch calculated Andrew Sprowle's total losses during the American Revolution as £20,703.01 Sterling.

Death

Sprowle tried to leave Virginia on May 25, 1776, after the Continental Army took control. But he was not successful. After the British left Portsmouth in May 1776, Sprowle and other Loyalists went with Dunmore's fleet to Gwynn's Island (now Mathews County, Virginia).

His widow, Katherine, said that the difficulties were too much for Mr. Sprowle's age. He died on May 29, 1776, while still on a ship at Gwynn's Island. On that same day, Sprowle signed two additions to his 1774 will. He recognized Katherine as his legal wife and heir, along with his grandnephew John Hunter Jr.

Some people say Sprowle was buried in an unmarked grave, but this is debated. A Patriot officer who visited Gwynn's Island after the British left reported seeing Sprowle's grave.

Thomas McCulloch, Sprowle's business manager, said that Andrew Sprowle stayed with the Governor's fleet until the end of May 1776. He died at Gwynn's Island "among the wreck of his property."

A historian named H.J. Eckenrode wrote in 1916 that Sprowle "had no real partisanship, merely desiring to live in peace." But in Norfolk, it was not possible for someone in his position to stay neutral. Sprowle could not leave his property and chose to stay with his goods, which cost him dearly. In 1991, Thomas Costa concluded that Sprowle was a Loyalist, even if he was a bit hesitant. He likely felt his loyalty was with the British. As a merchant, he worried about trade stopping. He saw the conflict as a threat to property and viewed the Patriots as the main enemies of property.

Andrew and Katherine Sprowle were not alone as Loyalists. About 20% of the population remained loyal to Great Britain. By 1783, about 60,000 Loyalists had fled to other parts of the British Empire.

Deaths in Sprowle's Enslaved Workforce

Thomas McCulloch carefully recorded Andrew Sprowle's financial losses. He also noted the terrible deaths of many of Sprowle's enslaved workers due to disease and being taken away. McCulloch's main concern was to calculate losses for future payment.

McCulloch testified that some enslaved people were saved and taken to New York. But 29 enslaved people died from contagious diseases they caught on the fleet between December 1775 and July 1776. Their value was estimated at £1,200 Sterling.

Sir Andrew Snape Hamond, a British naval commander, said that most of the Black troops had been inoculated before leaving Norfolk. They survived smallpox but then got a fever, possibly typhus, at Gwynn's Island.

British records confirm that three enslaved individuals, Dorothy Bush (age 36), Venus Profit (age 50), and James Knapp (age 12), were safely moved to Canada in 1783. Venus Profit and Dorothy Bush are called "Venus" and "Moll" in Andrew Sprowle's 1774 will. Records for Dorothy Bush, also called "Doll," state she was "Formerly Slave to Andrew Sproule, Portsmouth. Left 7 years ago, Certificate from General Birch. She says her master Andrew Sproule [Sprowle] gave her freedom before he died which was seven years ago." If this is true, Dorothy Bush was the only enslaved person Andrew Sprowle freed. She was also one of the last people to see him alive.

Legacy

After her husband's death, Katherine Sprowle immediately tried to get back Andrew Sprowle's estate or get paid for it. On June 28, 1776, she wrote to Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, emphasizing her difficult situation and her determination to get compensation.

After the Revolutionary War, Thomas McCulloch, working for Katherine and her son John Hunter Jr., calculated Sprowle's total property losses as £20,703.01 pounds sterling. They also listed debts owed to Andrew Sprowle totaling £10,703 pounds sterling.

Katherine constantly asked for help from the British Loyalty Board, Lord Duncanon, the State of Virginia, and even Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. She had some limited success.

Despite the war's destruction, some of Sprowle's estate survived. This included part of the Gosport shipyard and some of his enslaved workforce. Records from the Virginia House of Burgesses show that in 1780, the council advised the Governor to buy part of Andrew Sprowle's estate known as Gosport for a shipyard. They also wanted to buy enslaved men from his estate to work in a lead mine.

Other records from 1779 state that the "auditor be directed to issue McLauchlan as attorney of Andrew Sprowle deceased, for so much money as has been accounted for the hire arising from his slaves." The state auditor directed the Treasury to pay £111.68 for the hire of his stores and enslaved people. Another order directed that "Katherine Sprowle now Douglas and John Hunter, [Andrew Sprowle's grandnephew] 'receive the Negros now in public labor belonging to the estate of Andrew Sprowle and give order for their delivery."

Katherine Sprowle was a strong and outspoken advocate in her search for payment. She was an educated and brave woman in a time when women were expected to be quiet. On March 6, 1783, the Loyalist board finally ruled in Katherine Sprowle's favor. They confirmed her marriage and praised her husband's efforts for the British government. However, they gave her a smaller pension than she expected.

See Also

- Norfolk Naval Shipyard

- Loyalist (American Revolution)

- Slavery in the United States

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |