Ann Randolph Meade Page facts for kids

Ann Randolph Meade Page (born December 3, 1781 – died March 28, 1838) was an important leader in the Episcopal Church who worked to reform slavery. She grew up in a family that owned enslaved people. Her husband was also one of the largest slaveholders in Frederick County, Virginia. Ann did not believe in slavery. Even though she could not free enslaved people right away, she focused on making their lives better. She taught them to read and write, shared religious lessons, and helped them learn many useful skills for home and work.

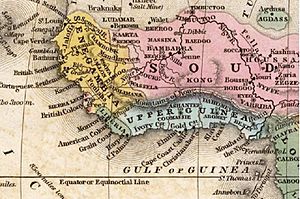

After the American Colonization Society was started, and after her husband passed away, she freed the enslaved people. She helped them get ready to leave the United States and travel to Liberia in Africa. There, they and their families could live as free people.

Early Life and Family

Ann Randolph Meade was born on December 3, 1781. Her mother was Mary Fitzhugh Grymes Randolph, and her father was Colonel Richard Kidder Meade. Her father was an aide to General George Washington during the American Revolutionary War. Ann was born at "Chatham Manor" in Stafford County, Virginia, near Fredericksburg, Virginia. She grew up on a plantation called "Lucky Hit". This plantation was first in Frederick County, Virginia, but it is now in Clarke County, Virginia.

Ann learned about school subjects and religion from her mother. Her mother was an Evangelical Christian. Even though her family was wealthy, her mother taught her to live simply and to help enslaved people. Her mother believed it was more important to care for others than to live a fancy life. She taught Ann, "your guests see your well-spread table, but God sees in the negro cabin." This meant that God cared about how they treated everyone, including enslaved people. The family lived simply and helped those in need.

Ann was the first of eight children. Her siblings included Richard, William, Susanna, David, Mary, and Lucy. Her brother, William Meade, later became a bishop. He encouraged people to have a strong personal relationship with God and to live a moral life. He also supported missionary work and religious reform.

Marriage and Family Life

Ann married Matthew Page on March 23, 1799. Matthew was a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, which was part of the state government. He was also a planter who owned a large 2,000-acre plantation in Berryville, Virginia. About 200 enslaved people lived and worked on his land. Matthew built a large house in Boyce, Virginia and named it Annefield in honor of his new wife.

Ann and Matthew had one daughter, Sarah Walker Page. On February 28, 1833, Sarah married Charles Wesley Andrews. Charles was inspired by Ann's brother, William, and became a bishop in 1832. Charles believed that slavery was wrong. He supported freeing enslaved people and helping freed African Americans move to Liberia. He lived by strict religious rules. Sarah and Charles were very active members of the American Colonization Society. In 1844, Charles published a book about Ann called Memoir of Mrs. Anne R. Page. Sarah and Charles had two daughters and one son.

Working to End Slavery

After she got married, Ann became very sad. It was hard for her to deal with the fact that her husband was one of the biggest slaveholders in Frederick County, Virginia, while she believed that no one should be enslaved. She felt that God had called her to stop "the evil power of slavery," especially in her own home. Because she could not end slavery right away, she felt sad every morning and went to sleep feeling afraid. In 1816, her spirits lifted when the American Colonization Society was created.

Even though she was a major slaveholder, Ann was deeply moved by her religious beliefs. She especially followed the Golden Rule, which means treating others as you want to be treated. This belief, along with a powerful religious experience, pushed her to free enslaved people.

One Sunday after church, I was going to dinner at someone's house, as was common. But God's spirit guided me to return to my quiet home, where no white person was around. This was the first time I had gone home on Sunday for a religious reason. I went to my room and thought deeply about judgment and eternity. While I was there, an old blind enslaved woman, who was a dear child of God, was led into the room. We started talking, and she spoke about having complete trust in Christ. Her words made a lasting impression on me, and I remember them clearly even now. I believe I owe much of my religious joy in later years to her, with God's help. She was an old, dark-skinned woman, and I often visited her in her small house. I saw how strong her faith was. She was a living example of Christ's spirit in a person, bringing hope of glory.

—Ann Randolph Meade Page

Ann wanted to free the enslaved people, but her husband, Matthew, would not allow it. So, she did what she could. She provided care and education to the enslaved people on their plantation. For example, in 1814, she made plans for better homes for the enslaved families. These plans included trees for shade and fruit, good airflow, and furniture. The enslaved people on the Page's plantation often chose to learn to read and write, and many became Christians. Men learned skills like shoemaking, blacksmithing, and wheelwrighting, in addition to farming. Women learned various domestic skills.

In 1816, the American Colonization Society was formed. Ann, along with her daughter Sarah Page Andrews and her brother William Meade, supported this group. The Society helped transport and settle freed enslaved people in Liberia. Ann worked with her brother and with Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis to end slavery and improve the lives of enslaved people.

Ann called her efforts "this holy work" and prayed, "Oh, that slavery's curse might cease." She worked even harder to free enslaved people after her husband, Matthew, died in 1826. Ann also supported spreading Christianity in Africa. She became an active and supportive member of the American Colonization Society. She helped guide the white men who worked as agents and managers for the Society, including her future son-in-law, Christopher Wesley Andrews. She prepared the enslaved people at Annefield for their new lives in Africa. She even gathered a year's worth of supplies to send with them to Liberia. On April 4, 1831, she wrote to Ralph Randolph Gurley of the American Colonization Society. She explained that she was planning for the African American people from Annefield to move to Liberia. There, they would have a better chance at a free future, and adults and children would not risk being forced back into slavery.

Several ships carried freed African Americans to Liberia. The first ships sailed in 1832, followed by others in 1834 and 1836. Ann's work to free enslaved people made her known as "one of the most generous of colonizationist emancipators." The people she freed were mostly members of a large family who shared the same Page last name.

Even though they were wealthy slaveholders, few people who worked against slavery, whether from the North or South, were as dedicated and influential as Ann R. Page and Mary L. Curtis. They supported colonization, a movement that started and was most popular in the Upper South. They liked it because it used moral persuasion, offered African Americans a safe place away from prejudice and unfair laws in the United States, and helped calm white people's fears about the growing number of free Black people.

—From the chapter about Ann R. Page and Mary L. Curtis in Virginia Women: The Lives and Times

Death

Matthew Page died in 1826. Ann Page passed away on March 28, 1838, at Annefield. They were both buried at Old Chapel Cemetery in Clarke County, Virginia.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |