Anne Warner (scientist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anne Warner

|

|

|---|---|

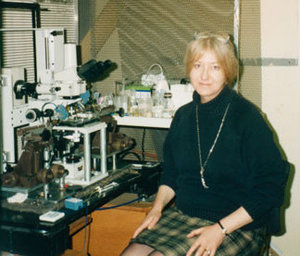

Warner in her laboratory (early 1990s)

|

|

| Born |

Anne Elizabeth Brooks

25 August 1940 |

| Died | 16 May 2012 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | University of London (PhD) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | electrophysiology |

| Institutions | University College London |

| Thesis | The effect of pH on the membrane conductance of skeletal muscle (1964) |

| Doctoral advisor | Otto Hutter |

| Influenced | |

Anne E. Warner (born August 25, 1940 – died May 16, 2012) was a brilliant British biologist. She was a professor at University College London (UCL). Anne Warner studied how living things develop and change shape, a field called morphogenesis. She was famous for her important research and for leading many science projects and groups. She was especially known as a cell electrophysiologist, someone who studies the electrical activity of cells. She also helped guide science policy and founded the UCL centre CoMPLEX.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Anne Elizabeth Brookes was born on August 25, 1940, in Golders Green, England. She was the only child of Elizabeth and James Frederick Crompton Brooks. Her father was an engineer.

Anne went to Pate's Grammar School for Girls in Cheltenham. After that, she studied at University College London. She earned her first degree in physiology, which is the study of how living things work.

She continued her studies to get her PhD degree. She did this at the National Institute for Medical Research. Her supervisor was Otto Hutter. Anne finished her PhD in 1964 when she was just 23 years old. In the same year, she started working at the Institute. She began researching how pH (a measure of acidity) affects the electrical signals in muscle cells.

Amazing Research on Cell Communication

Anne Warner was involved in many different research projects. She is most famous for her work on structures called gap junctions. She studied how these tiny connections between cells help in embryological development. This means she looked at how a tiny embryo grows into a fully formed animal.

Discovering Gap Junctions' Role

Scientists had been trying for 20 years to prove that gap junctions were how cells "talked" to each other. They wanted to know how cells connected to form tissues during development. Anne Warner, with her colleague Sarah Guthrie, finally proved this!

They studied the embryos of frogs. Warner noticed something called "electrical coupling" between cells. This means if one cell's electrical charge changed, the cell next to it also changed. This showed that gap junctions were like tiny bridges. They allowed ions (electrically charged particles) to pass directly from one cell to another.

However, Warner also noticed that these gap junctions were not always there. They appeared during some stages of development but not others.

Proving Their Importance

To prove how important gap junctions were, Warner did more experiments in the 1980s. She tried to block these connections to see what would happen. She used 8-cell embryos of the African clawed frog, called Xenopus.

- She injected a special antibody into the embryos. This antibody was designed to block the channels within the gap junctions.

- To check if the block worked, she injected dyes into the cells. If the dye couldn't pass to the next cell, it meant the gap junctions were blocked.

- She also confirmed that the electrical coupling she saw before was now gone.

After successfully blocking the gap junctions, Warner let the embryos grow. She observed that the toads developed abnormally. This was a huge discovery! Anne Warner showed that gap junctions are absolutely necessary for cells to develop normally from an embryo into a mature organism. Her work greatly added to our understanding of how cells grow and mature.

A Leader in Science

Besides her research, Anne Warner was a leader in many scientific groups. She was a member of important organizations like the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom (MBA) and the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine. She also served on the editorial board of The Journal of Physiology.

Return to University College London

In 1976, Warner returned to her old university, University College London. She became a lecturer at the Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine. Over the years, she held several important positions there. She became a Reader in the Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology. In 1986, she received a special honor: Royal Society Foulerton Professor. She was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1985, which is a very high honor for scientists.

Founding and Leading Organizations

Among all her roles, Warner is perhaps best known for two things:

- Being the Vice-President of the Marine Biological Association (MBA) council. She helped the MBA survive and thrive. She started the cell physiology Workshop in 1984, which helped train many cell physiologists around the world.

- Being the Director of CoMPLEX (Centre of Mathematics, Physics, and Life Sciences) at University College London. She was a co-founder of this organization. She brought together scientists from different fields to work on biology. CoMPLEX became a model for similar groups in other countries.

Anne Warner's work with these organizations created a lasting impact. Many of the programs she started are still used today.

Personal Life

Anne Warner met her husband, Michael, when they were both part of the stage crew at University College London. Sadly, her husband passed away a few weeks before her.

Later in her life, Anne became ill. She was no longer able to be physically involved in all the organizations she loved. However, she stayed in touch and continued to offer advice. She passed away on May 16, 2012, at University College Hospital, Camden, due to a sudden illness.

A colleague from UCL wrote about Anne Warner after her death. They described her as a strong and determined person. She brought her colleagues together with her drive to solve problems. Anne Warner dedicated her life to making a big difference in her field of research and in the many organizations she was a part of.

See also

In Spanish: Anne Warner para niños

In Spanish: Anne Warner para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |