Anthony Durnford facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anthony William Durnford

|

|

|---|---|

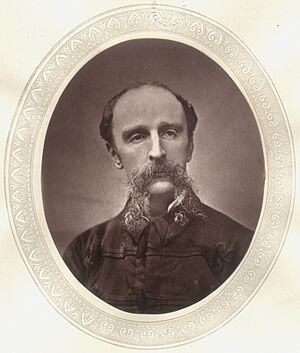

Anthony Durnford in 1870

|

|

| Born | 24 May 1830 Manorhamilton, County Leitrim, Ireland |

| Died | 22 January 1879 (aged 48) Isandlwana, South Africa |

| Buried |

St George's Garrison Church, Fort Napier, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1848–1879 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-Colonel |

| Unit | Royal Engineers |

| Commands held | No. 2 Column, Zululand Invasion Force |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Tranchell |

Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony William Durnford (born May 24, 1830 – died January 22, 1879) was an Irish officer in the British Army. He was part of the Royal Engineers, a special unit that built things like bridges and forts. Durnford is mostly known for his role in the Anglo-Zulu War, especially for the British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Anthony Durnford was born in Manorhamilton, County Leitrim, Ireland. His family was very involved in the military. His father, Edward William Durnford, was also a general in the Royal Engineers. Anthony's younger brother, Edward, also served in the British military.

In 1846, Anthony joined the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, England. He became a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in 1848. Early in his career, he helped build defenses for a harbor in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He even helped save parts of the harbor defenses from a fire in 1853.

Durnford wanted to fight in the Crimean War, but he wasn't sent. He also served in Malta and Gibraltar, gaining experience in different places. In 1864, he was sent to China, but he got sick from the heat and had to return to England. After he recovered, he spent six years on regular duties before being sent to South Africa in 1871.

Duty in South Africa

Durnford arrived in Cape Town, South Africa, in January 1872. He was promoted to major and then to lieutenant-colonel soon after. He spent a lot of time in King William's Town. He wrote that he respected the local African people, calling them "honest, chivalrous and hospitable." He kept this view throughout his life.

Later, he was stationed in Pietermaritzburg. There, he became friends with Bishop Colenso and his daughter, Frances Ellen Colenso. Frances later wrote two books that supported Durnford's military reputation: My Chief and I and History of the Zulu Wars.

Durnford saw some action during a conflict involving a chief named Langalibalele. He showed great bravery but was wounded. His local Basuto troopers stayed loyal to him, even when others left. In 1878, Durnford helped decide the border between the Transvaal and the Zulu Kingdom. He was also put in charge of creating an African auxiliary force, which became known as the Natal Native Contingent.

The Anglo-Zulu War

Durnford was one of the most experienced officers in the Anglo-Zulu War. He was known for his strong leadership and energy. However, he could also be stubborn. He was chosen to lead the No. 2 Column of the British invasion army. This force included African troops, like the Natal Native Horse.

On January 20, Durnford's group was ordered to Rorke's Drift to help another British column. The next day, part of his force camped near Rorke's Drift. On the evening of January 21, Durnford was ordered to Isandlwana. Another officer, Lieutenant John Rouse Merriott Chard, was sent back to Rorke's Drift to prepare defenses.

Around 10:30 AM on January 22, Durnford arrived at Isandlwana with his troops and a rocket battery. As a Royal Engineer, Durnford was technically in charge of the camp, even though Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Pulleine had been left in control. Durnford decided to move forward and attack a Zulu force that seemed to be moving towards the British camp. He asked Pulleine for more soldiers, but Pulleine was hesitant because his orders were to defend the camp.

Durnford's Last Stand

Durnford was killed during the battle at Isandlwana. Some people later criticized him for taking soldiers out of the camp, which weakened its defenses. However, Durnford believed in attacking the Zulus wherever they appeared. His actions and his troops managed to stop a large part of the Zulu army for a while.

When their ammunition ran out, Durnford and his men fought their way back towards the main camp. In a final brave effort, Durnford told his local troopers to escape. He then died fighting alongside other British and colonial soldiers. They were trying to keep open the only escape route. Durnford's body was later found near a wagon, surrounded by his fallen men.

The disaster at Isandlwana had several causes. One issue was that the roles of Durnford and Pulleine were not clear. Also, the British commander, Lord Chelmsford, didn't have good information about the Zulu forces. He also made the mistake of not fortifying the camp, which went against his own orders.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |