Arpilleras facts for kids

An arpillera (pronounced ar-pee-YEH-rah) is a bright, patchwork picture. It is usually made by groups of women, who are called arpilleristas. These special fabric pictures became very popular in Chile during the time it was ruled by a military government (from 1973 to 1990). This government was led by Augusto Pinochet.

Arpilleras were made in workshops. These workshops were set up by the Catholic Church in Chile. The church's human rights group, called the Vicariate of Solidarity, then secretly sent the arpilleras to other countries. Making arpilleras gave the women a way to earn money. Many of them had lost their jobs or had husbands and children who had disappeared. These missing people were known as desaparecidos.

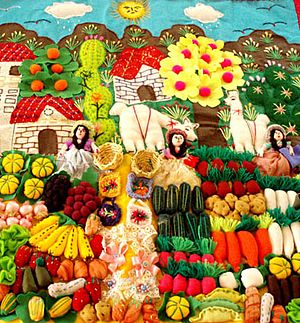

Arpilleras are usually made from simple materials. These include burlap and small pieces of cloth. Often, arpilleras showed political messages. They showed scenes of poverty and how the government treated people badly. These pictures helped to speak out against the human rights problems under Pinochet's rule. Because of this, the Chilean government tried to punish those who made or supported arpilleras. Today, arpilleras are seen as a powerful example of women's art used to resist an unfair government. However, newer arpilleras often show less political themes, like peaceful country life.

Contents

Chile's Difficult Past

The Pinochet Government

In September 1973, Chile faced a lot of political tension. The elected government, led by Salvador Allende, was overthrown. This happened in a coup d'etat (a sudden takeover of power) by the Chilean military. Augusto Pinochet led this takeover. The US government also supported this change. The military took over because they were worried about Allende's socialist ideas.

From the very start, Pinochet's government was known for many human rights problems. Right after the takeover, the new leaders declared a state of emergency. They arrested many people without reason. All political parties and worker groups were banned. Over the next few years, thousands of people were tortured, questioned, or killed.

It's hard to know exactly how many people were killed or "disappeared." These were people who vanished into prisons or unmarked graves. A report in 1991 said that over 2,000 people were killed. Another report in 2005 stated that 38,254 people were jailed for political reasons. Most of these people had been tortured.

The change from Allende's socialist plans to Pinochet's new economic ideas was very sudden. It caused a "shock" to Chile's economy. Government spending on social programs dropped quickly. Many people lost their jobs. By 1975, almost 19% of people were unemployed. This made many Chileans poorer and led to food shortages. People with little money could not pay for basic services like water and electricity. The government started charging for these services to make money for the military.

The Pinochet government also had strict ideas about women. They believed women should be quiet and not involved in politics. They should focus only on being wives and mothers.

How Women Were Affected

Women from poor and working-class families were hit especially hard by these changes. Many were left without any income. This was because of widespread job losses and the disappearance of family members. For the first time, these women had to find work outside their homes.

Pinochet's rise to power also changed how women could organize. Women who supported the government were praised. They were seen as examples of good morals. They joined groups that promoted family values. But many other women formed groups to oppose the government. They also needed to find ways to survive financially.

These groups included those that fought for human rights. They also sought justice for the desaparecidos. Other groups helped each other by providing meals or teaching useful skills. The Catholic Church also set up workshops. These workshops aimed to give women jobs.

Where Arpillera Workshops Began

Isla Negra

Before Pinochet's time, arpillera workshops were already starting. One workshop was created in a countryside area called Isla Negra. A kind woman named Sra. Leonora Soberino de Vera started it. The arpilleras from this workshop were inspired by folk tales and happy memories. They showed themes of joy and a wish for a peaceful country life.

These women found customers from all over the world. The government and museums helped them. Famous people like Pablo Neruda and Violeta Parra also supported them. This led to a huge demand for their arpilleras. This demand sometimes made it hard for the women to keep up. But with Sra. Leonora's help, the women kept meeting to create arpilleras.

Santiago

After the 1973 takeover, several Catholic Church groups started to resist the military government. They were inspired by a movement called liberation theology. One of these groups helped start the first arpillera workshops in Santiago. This group was called the Committee of Cooperation for Peace in Chile.

The women in these new Santiago workshops were inspired by the work from Isla Negra. However, the wool embroidery used in Isla Negra was too expensive and took too much time. So, the Santiago women created their own methods. In 1975, this church committee was forced to close down.

The Vicariate of Solidarity then took over. This group was part of the Chilean Catholic Church. It continued the fight for human rights in Chile. The Vicariate spoke out against the military government. It helped Chilean citizens with legal aid, health care, food, and jobs.

In March 1974, the first arpillera workshops by the Vicariate of Solidarity began. Valentina Bonne, a church official, led this effort. The workshops aimed to give unemployed women a small income. They also created a community for emotional support. By selling these protest artworks, they hoped to get international attention. The Vicariate also provided materials for the women.

Women would meet in secret places, like church basements. This helped them avoid being caught by the government. Most arpilleras were made in workshops. But some were even made from prison. About 14 women joined the first workshops. Many of them came from the poor areas (shantytowns) of Santiago. By 1975, there were ten workshops in Santiago. At its busiest time, there were about 200 workshops in Santiago. Each had about 20 women meeting three times a week.

In these workshops, women would gather and sew arpilleras to earn money. They also talked about how to make the best arpilleras. They discussed design, quality, and themes. This helped make sure the arpilleras were well-made and consistent. At the end of each meeting, a treasurer collected the arpilleras. They were then sold overseas to human rights groups and Chilean exiles.

Usually, a woman could only make one arpillera per week. This was unless she was in great financial need. In urgent cases, women could make two arpilleras a week. A small group of six arpilleristas from the workshop would check the quality. If an arpillera was approved, it was collected and sold once a month for $15.

During the dictatorship, arpilleras became known worldwide. The Catholic Church, Amnesty International, and Oxfam UK helped distribute them. The main buyers were human rights activists in North America and Europe. They wanted to show support for the victims of the government. Chilean exiles living abroad also bought them. They hoped to raise awareness about poverty and unfair treatment in Chile. After getting paid, each woman gave 10% of her earnings to a group fund. This helped keep the workshop going.

What Arpilleras Look Like and What They Show

How They Are Made

The workshops and the Vicariate set rules for arpilleras. These rules covered how many figures could be in a picture. They also decided on sizes, how things were arranged, colors, and themes.

Arpilleras were meant to be simple. This made them easy for everyday women to create, even without art training. The Vicariate and the women had very few resources. So, arpilleras were made from the cheapest materials available. These included flour or wheat sacks (made of jute, flax, or hemp), fabric scraps, used thread, and discarded items.

Most arpilleras were made on thick burlap canvases. Colorful fabric pieces were stitched and embroidered together. This was done in an appliqué style. They formed flat images of people, buildings, streets, and landscapes.

Many arpilleras also had 3D parts. Small dolls were stitched onto the fabric. These dolls were meant to show the special qualities of the people they represented. Arpilleristas also used other items to make things pop out. They used tin pieces for pots and pans. Matchsticks and broom handles became parts of scenes. Plastic pill casings were used as tiny bowls.

Sometimes, arpilleristas would add a small pocket on the back of the arpillera. Inside, they would place a paper with a written description. These descriptions often spoke of wanting support and explained the human rights problems in Chile. The paper sometimes had the arpillerista's name. But usually, they did not write their names to stay safe.

There are three main ways arpilleras are made:

- The Flat Method: Fabric pieces are sewn onto the surface using embroidery stitches around them.

- The Raised Method: Dolls and other objects are slightly lifted from the surface with embroidery stitches.

- The Glue Method: Different colored wool is glued to border the fabric pieces that are glued to the surface.

When an arpillera is finished, it usually has a crocheted wool border. They typically range in size from about 9 by 12 inches to 12 by 18 inches.

What They Show

While some arpilleras showed happy memories, most depicted scenes of hardship. The workshops encouraged talking about political problems and unfair economic situations. Sometimes, they even openly said their goal was to create enough international anger to bring back democracy. So, the arpilleristas often chose political themes for their art. Sometimes, several arpilleras with similar themes were sewn together to form large murals.

Arpilleras often showed a contrast. They used bright, colorful fabric pieces. But their messages were serious and sad. For example, colorful triangular fabric scraps were often placed along the horizon. These represented Chile's beauty and wealth across different regions and seasons. However, sad messages about unfair living conditions or lack of opportunities were shown. These were often portrayed by a dividing figure, like a building, street, river, or fence.

So, besides everyday scenes of Santiago's poor neighborhoods and the Andes mountains, arpilleras often showed human rights problems. They depicted government violence, poverty, and women's lack of political rights. For example, some arpilleras showed bones, body bags, or people being questioned by military police. Others showed village children eating from big soup pots in shared kitchens. Or people waiting in line to get food. Some arpilleras also showed women outside prisons. These women would chain themselves to the prison fence, where their friends and family were held.

Arpilleras also often showed the faces of family members who had disappeared. Marjorie Agosín, a writer who studies arpilleras, compared this to the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina. Those mothers wore photos of their missing children during a difficult time called the Dirty War. Many arpilleras also had text stitched into the fabric. These short messages demanded to know what happened to the desaparecidos. They also spoke out against the lack of political and economic rights for women.

A sociologist named Jacqueline Adams noted a change in the early 1980s. The Catholic Church became less critical of Pinochet's government. They even fired some of the Vicariate's more outspoken staff. She believes this led to a change in the arpilleras' content. She says arpilleristas became less direct in their protests. They shifted from political themes to peaceful images of daily life. This was because they knew the Vicariate would reject any work that seemed too rebellious. Still, even these arpilleras showed the effects of political and economic hardship. For example, they showed people illegally connecting to power lines for electricity. Or people getting water from a pump.

The Impact of Arpilleras

On Women

About 80% of the arpilleristas came from poor or working-class families. The other 20% were from upper-middle-class homes. These wealthier women were mainly motivated by the disappearance of family members. They also wanted to show support for victims of political violence.

Some women already had political beliefs when they joined the workshops. Many had supported Salvador Allende. But most had not been involved in politics before. They later developed pro-democracy ideas. This happened through the political discussions in the workshops. They also shared experiences of losing family members to the government. As women kept talking about the government, they learned more about how power worked in Chile. They learned about their rights by going to talks. Then they would protest through hunger strikes, marches, and other ways.

At home, the money women earned from selling arpilleras helped their families. It improved their children's education, health, and overall well-being. However, the work women did in the workshops went against the idea that women should only be involved in home duties. Because of this, some women faced verbal and physical abuse from their husbands. But in some cases, the women's children and husbands also helped make arpilleras. This gave the women more free time.

Their Lasting Legacy

Since Chile became a democracy again, arpilleras have been shown all over the world. They have been displayed in the United States and throughout Europe. Major cities like Washington D.C. now have arpilleras made during Pinochet's time. Even Chilean government shops sell them.

The arpillera movement is praised for showing life under Pinochet's rule. It also bravely addressed human rights and gender issues. Some arpilleras were shown in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2014. About 500 arpilleras were also returned to Chile. They are now part of an exhibit in The Museum of Memory and Human Rights.

Chilean writer Isabel Allende said about arpilleras: "With leftovers of fabric and simple stitches, the women embroidered what could not be told in words. So, the arpilleras became powerful ways of political resistance... the arpilleras grew strong in a quiet nation. From church patios and poor neighborhoods, stories made of cloth and yarn told what was forbidden."

The formal workshops stopped in 1989 when Chile became a democracy again. But the tradition continued with independent arpilleristas. Modern arpilleras often show an idealized version of Chilean country life. These newer arpilleras are also made by machines. They are sold as wall hangings, cards, coin purses, and other souvenirs. You can find them in street markets and tourist shops. The Chile Crafts Foundation, for example, has stores in Santiago and at the airport. This helps tourists see Chilean culture and gives arpilleristas a way to sell their work.

However, modern arpilleras have also been criticized. Some believe they show a too-general picture of Chile. They might ignore the political history of arpilleras. But in 2011, some arpilleras in Chile did show political themes. They spoke out against how the government treated the native Mapuche people. Arpilleras have also inspired similar art in other countries. These countries, like Colombia, Peru, Zimbabwe, and Northern Ireland, have also faced government violence.

See also

In Spanish: Arpilleras para niños

In Spanish: Arpilleras para niños

- Violence against women

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |