Avery's Trace facts for kids

Avery's Trace was a very important road in early Tennessee history. It was the main path for settlers moving from the Knoxville area in East Tennessee to the Nashville area. People used this road from 1788 until about the 1830s.

In 1787, North Carolina wanted more people to move west into the new land that would become Tennessee. So, they decided to build a road. This road would help settlers reach the Cumberland Settlements, which included Nashville. Peter Avery, a skilled hunter who knew the land well, was chosen to lead the way. He helped mark out this new trail through the wild forests.

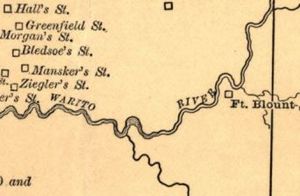

The trail followed paths that the Cherokee people had used for a long time. These paths were also used by buffalo. Avery's Trace started at Fort Southwest Point in Kingston. It went through the Cumberland Mountains and into what is now Jackson County, Tennessee, reaching Fort Blount. From there, it wound through hills and valleys to Bledsoe's Fort (near Castalian Springs). Then it went to Mansker's Fort (near Goodlettsville), and finally to Fort Nashborough. These forts were safe places for travelers to rest and find protection along the Trace.

Contents

First Journeys on the Trace

In 1787, North Carolina sent 300 soldiers to help protect the Cumberland Settlements. These soldiers also helped Peter Avery mark the trail. Each soldier received a land grant of 800 acres (3.2 km²) for their year of work. They cleared a path about 10 feet (3 meters) wide. That same year, 25 families traveled along the new road.

By 1788, Avery's Trace was still very rough. It was just a trail marked by trees with cuts in them to guide pioneers. For many years, only people on horseback with pack horses could use the rugged path. Travelers wrote in their journals about the difficulties they faced. The 300-mile (480 km) trip often took several days. The Trace was known by different names, including "Walton Road," "North Carolina Road," "Avery's Trace," and sometimes "The Wilderness Road."

Trace Passes Through Cherokee Land

Part of Avery's Trace went through land belonging to the Cherokee people. Because of this, the Cherokee asked for a toll from settlers using the road. This often led to arguments. Even though colonists and Cherokees signed a treaty to solve these problems, fighting still broke out. Sadly, 102 travelers were killed along the road by Cherokees during this time.

The North Carolina government ordered groups of 50 militia men to protect travelers. These groups would escort settlers when enough people gathered at the Clinch River to head west. In 1792, Americans built a blockhouse (a small fort) at the Clinch River. Governor William Blount put many soldiers on active duty. General John Sevier led these soldiers from the blockhouse. They began to provide armed escorts for people traveling on the Trace.

Trace Widened for Wagons

A few years later, the North Carolina government decided to make the Trace wider. They wanted to turn it into a road that wagons could use. They even raised money for this by holding a lottery. However, even as a wagon road, the Trace was still very bumpy and difficult to travel. Pioneers were warned to watch their horses closely, as Native American hunters sometimes took them. The war over the land had ended, so travelers no longer feared for their lives as much.

By the late 1790s, the road conditions varied greatly. Some parts were "bottomless" with mud, while others were "fine and dry." Wagons often sank deep into mudholes. In some places, the Trace was covered with flat stones, which made it hard for horses. Much of the way could only be traveled on foot. Rivers and streams had to be crossed by wading through them. At Spencer's Mountain, in what is now Cumberland County, the road became very steep and rocky. It was so bad that wagons needed brakes on all wheels and a tree tied to the back to slow them down. The top of the mountain was said to have no trees left because they were all used to slow down wagons.

Families Travel to the "Promised Land"

Even though the road was rough, it was the main way to reach the Cumberland Settlements. Single travelers or pioneer families would load their belongings into wagons. They would meet other pioneers at the Clinch River. When a large enough group had gathered, soldiers would join them. They would drive their horses across the Clinch River to begin their journey into the wild unknown. Many believed they would find a "promised land" at the end of their trip. Many were seeking land they had been given for serving the new country. They faced a long and hard trail with many dangers.

Pioneers camped along the way, cooking over campfires and sleeping under the stars. Sometimes, they were lucky enough to find families living along the Trace. These families would offer shelter and food for them and their horses. But such stops were rare. One traveler wrote that "the houses are so far apart from each other that you seldom see more than two or three in a day." Sometimes, people charged high prices for any shelter or food. The land they traveled through was beautiful, with hills and valleys full of tall cane plants, huge trees, and tangled vines. Many who made the journey described it as 300 miles (480 km) of wilderness. This wilderness was home to wolves, mountain lions, coyotes, deer, and herds of buffalo. Along the Trace, settlers would turn off to reach their own land grants. By the last fort, Fort Nashborough, often only the soldiers remained. These soldiers usually picked up another group of settlers going back East. A traveler reported that families were always moving in and out of the area. They were either going "back to whence they came or onward to other settlements."

Famous Travelers on the Trace

Many important people traveled along Avery's Trace. These included Andrew Jackson (who later became president), Judge John McNairy, Governor William Blount, and Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans (who later became King of France). Other notable travelers were Bishop Francis Asbury, French botanist André Michaux, Tennessee Governor Archibald Roane, and Thomas "Big Foot" Spencer. Avery's Trace stands as a reminder of the brave travelers and families. They had the courage to make such a difficult journey. They were searching for a new life for themselves and for future generations.

Images for kids