Battle of Chalgrove Field facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Chalgrove Field |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

Monument to John Hampden on the battlefield, erected in 1843 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,150 cavalry; 350 dragoons 500 infantry |

900 cavalry (200 engaged); 100 dragoons |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20-45 (estimate) | max 50, unknown prisoners | ||||||

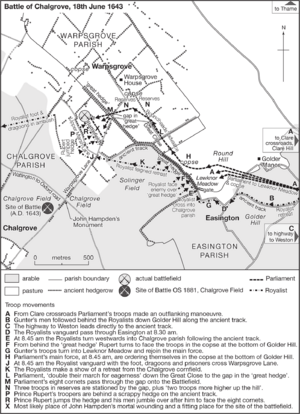

The Battle of Chalgrove Field happened on 18 June 1643, during the First English Civil War. It took place near Chalgrove, in Oxfordshire, England. This battle is most famous because John Hampden, an important leader for the Parliamentarian side, was badly hurt here and died a few days later.

The battle began when Prince Rupert, a Royalist commander, led his cavalry from Oxford. He hoped to capture a convoy carrying £21,000 for the Parliamentarians. Even though he didn't get the money, his troops seized supplies and prisoners.

As Prince Rupert's forces headed back to Oxford, they were chased by Parliamentarian cavalry led by John Hampden. Prince Rupert decided to stop at Chalgrove and fight back. He quickly defeated the Parliamentarian troops before their main force, led by Sir Philip Stapleton, could arrive.

This easy victory boosted the Royalists' spirits. It also made many people criticize the Parliamentarian commander, the Earl of Essex, for not stopping the raid. Chalgrove Field was the first of several Royalist victories over the next six months.

Why the Battle Happened

When the First English Civil War started, both sides thought it would end quickly after one big battle. But 1642 showed them it would be a long fight. The Royalists made Oxford their wartime capital and tried to connect their supporters across England and Wales. Meanwhile, Parliament worked to control the areas they already held.

Peace Talks and Royalist Needs

There were peace talks in February 1643, but neither side was serious about them, so they failed. The Earl of Essex, who led the Parliamentarian army, captured Reading on 27 April. This broke the line of outposts that protected Oxford.

The Royalists needed more weapons. Parliament controlled most of England's major ports and arsenals, making it hard for the Royalists to get supplies. In February, Queen Henrietta Maria bought many weapons from the Dutch Republic. These weapons landed in Bridlington, Yorkshire, and plans began to move them to Oxford.

Royalist Raids and Parliamentarian Delays

On 16 May, gunpowder arrived in Oxford, guarded by 1,000 soldiers. The Royalists also benefited from sickness among Parliamentarian troops. The Earl of Essex was slow to act, saying he needed more supplies and money. This delay gave the Royalists time to clear a path to Oxford. The Queen's arms convoy left York on 4 June with 5,000 cavalry.

A few days later, Parliament sent Essex £100,000 worth of supplies from London. This included £21,000 in cash to pay his soldiers. Meanwhile, Royalist cavalry from Oxford raided nearby Parliamentarian towns. Essex failed to stop these raids.

Parliament was angry and ordered Essex to act. He finally left Reading for Thame on 10 June. The Royalist raids were partly meant to distract from the Queen's convoy, which reached Newark on 16 June.

The Raid on Chinnor

On 17 June, Essex sent 2,500 men to attack a Royalist outpost at Islip. But the Royalist soldiers were ready, and Essex's men retreated. As they left, a Scottish soldier named Sir John Urry switched sides. He gave the Royalists information about the London convoy and where Essex's troops were.

Seeing a chance, Prince Rupert left Oxford at 4:00 PM that day. He had 1,200 cavalry, 350 dragoons (soldiers who rode horses but fought on foot), and 500 infantry (foot soldiers). Essex had put most of his troops in the north, leaving his southern positions open. John Hampden carefully checked his guards before going to bed.

Many Parliamentarian troops at Chinnor and Postcombe were tired from the failed attack on Islip. They didn't post guards and were surprised when the Royalists attacked at 5:00 AM. Prince Rupert's men caused 50 casualties, captured prisoners, and took supplies. Prince Rupert decided to leave quickly before his escape route was blocked. By 6:30 AM, his forces were on their way back to Oxford.

The Pursuit

While three groups of Parliamentarian soldiers, led by Hampden and Major John Gunter, kept an eye on the Royalists, the local commander at Thame, Sir Philip Stapleton, quickly gathered a force to attack them. Several senior officers, who were in Thame to collect their regiments' pay, helped him form new units. With about 700 men, Stapleton set off in pursuit.

The Battle at Chalgrove Field

The Royalists moved slowly because of their prisoners and stolen goods. Their column stretched out for two miles. By 8:30 AM, the Royalist rearguard (the soldiers at the back) met Hampden and Gunter's men. They were joined by 100 dragoons led by Colonel Dalbier, an experienced German soldier.

Prince Rupert realized he couldn't outrun his pursuers. He ordered his infantry commander, Lunsford, to keep moving and secure the bridge at Chiselhampton. The Royalists' path led them along a narrow path called a 'Great Hedge'. This path had two thick, shoulder-high hedges on both sides. These hedges were used to mark boundaries and keep cattle from wandering off.

The Ambush and Fight

With their sides protected by the hedges, the dragoons under Lord Wentworth set up an ambush further along the hedgerow. Prince Rupert's cavalry formed up in an open field. By this time, the Parliamentarian forces on the scene had about 200 cavalry and the dragoons.

Dalbier moved his dragoons up to the hedge and fired at the Royalist cavalry. This made Prince Rupert attack. He reportedly jumped over the hedge while the rest of his men went around it. Dalbier's men, helped by Hampden and Gunter, tried to hold their ground. But they were greatly outnumbered and soon broke apart.

For once, Prince Rupert's men stopped chasing them. This was probably because their horses were very tired after riding all night. The Royalists then went back to Chiselhampton, where they stayed until the next day. Most reports agree that the fighting was over by the time Stapleton arrived with his main force.

Casualties and John Hampden's Death

It's not completely clear how many people were hurt or killed. This is partly because reports often didn't separate losses from the raid at Chinnor, the skirmish with the rearguard, and the battle itself. The Royalists reported about 45 casualties for both sides. Essex suggested 50 for each side.

Major John Gunter was killed near the hedge. The other important loss was John Hampden. He was wounded twice in the shoulder and died six days later because his injuries became infected. Later stories that his own pistol exploded and caused his injuries have not been proven true.

What Happened After

The Battle of Chalgrove Field made Prince Rupert even more famous. It showed his strong drive, determination, and aggressive style of fighting. In just a few hours, he gathered almost 2,000 men, made a plan, and carried it out. His quick counter-attack kept Stapleton's forces away.

This battle also helped hide Rupert's weaknesses. One problem was his cavalry's lack of discipline, which had cost the Royalists a victory at the Battle of Edgehill. At Chalgrove, this was less of an issue because their horses were exhausted from riding all night. Rupert was good at inspiring loyalty in his officers, but he didn't get along as well with other commanders.

Impact on Parliamentarian Leaders

Chalgrove Field increased unhappiness with the Earl of Essex. His only success in 1643 had been capturing Reading. The attack on Islip was slow, unlike Rupert's quick actions. Even though there were warnings of a possible raid, no one took precautions. Without Hampden and Gunter chasing them, the Royalists would have returned home without any trouble.

Essex's reputation was further damaged when Rupert's men spent the next day at Chalgrove. They were giving out their loot and getting ready for a grand entry into Oxford, while the Parliamentarian army just watched.

Royalist Successes and Hampden's Legacy

Chalgrove ended any danger to the Royalist arms convoy, which arrived in Oxford in early July. More importantly, it gave the Royalists a psychological advantage over their enemies. This was confirmed on 25 June when Urry attacked Wycombe. Essex then pulled his troops out of Oxfordshire. This allowed Prince Rupert to help with operations in the west, leading to the capture of Bristol on 26 July.

John Hampden's death was a huge loss for Parliament. His close friend Anthony Nicholl wrote that no kingdom had lost a greater subject, and no man a truer friend. Hampden's good reputation and leadership skills had been very important in preventing arguments among Parliamentarian leaders. This was especially true after the discovery of Edmund Waller's Plot on 31 May. Waller was related to many Parliamentarian leaders, including his cousin, William Waller, and Essex. The death of John Pym in December meant that Parliament's two most important leaders were gone in less than six months, during a time when the Royalists were almost always winning.

In 1843, George Nugent-Grenville, a politician and writer, paid for the Hampden Monument. It is located about 700 meters south of the main battle site. After much discussion about whether it was a 'battle' or a 'skirmish', English Heritage officially named it a registered battlefield in 1995.