Battle of Dürenstein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Dürnstein |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Third Coalition | |||||||

Marshal Mortier at the battle of Durenstein in 1805, Auguste Sandoz |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~14,000 (at end) | ~24,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~5,000 killed, wounded, captured | ~5,000 killed and wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Dürenstein was a fierce fight that happened on November 11, 1805, during the Napoleonic Wars. It was part of the War of the Third Coalition. The battle took place in a valley called Wachau in Austria, near the town of Dürenstein (which is now called Dürnstein). This area is about 73 kilometers (45 miles) upstream from Vienna, along the Danube river.

In this battle, a combined army of Russian and Austrian soldiers managed to trap a French division. This French group was led by Théodore Maxime Gazan and was part of a larger force called the Corps Mortier, commanded by Édouard Mortier. Mortier had spread his troops too thin while chasing the retreating Austrians.

The leader of the Coalition forces, Mikhail Kutuzov, tricked Mortier into sending Gazan's division right into a trap. The French soldiers found themselves stuck in a valley between two Russian armies. Luckily for them, another French division, led by Pierre Dupont de l'Étang, arrived just in time to help. The fighting lasted late into the night. Both sides claimed they won, but the French lost more than a third of their soldiers. Gazan's division alone lost over 40% of its men. The Austrians and Russians also had heavy losses, about 16%. A very important Austrian leader, Johann Heinrich von Schmitt, was killed during the battle.

This battle happened just three weeks after a large Austrian army surrendered at the Battle of Ulm. It was also three weeks before the big defeat for Russia and Austria at the Battle of Austerlitz. After Austerlitz, Austria left the war.

Contents

Understanding the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of big conflicts in Europe from 1803 to 1815. During this time, different European countries formed groups called "coalitions" to fight against the First French Empire, led by Napoleon. These wars changed how armies were formed and trained. Many countries started using "mass conscription," which meant that many ordinary citizens were made to join the army.

Under Napoleon's leadership, France became very powerful and conquered most of Europe. But this power quickly fell apart after a terrible invasion of Russia in 1812. Napoleon's empire was finally defeated in 1813–1814. Even though Napoleon made a dramatic return in 1815 (known as the Hundred Days), his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo ended the Napoleonic Wars.

The Danube Campaign of 1805

| Coalition Allies | French Empire & Allies |

|---|---|

The War of the Third Coalition involved the First French Empire and its allies fighting against several European powers. While some sea battles were important, the war was mostly decided on land. The main fighting happened in the Danube river valley, in two big campaigns: the Ulm Campaign and the Vienna campaign.

Austria joined the Third Coalition in 1805. Archduke Charles, the emperor's brother, had been working to improve the Austrian army. However, another leader, Karl Mack, took over and made changes too quickly. Mack's reports made the emperor, Francis II, decide to go to war against France, even though Archduke Charles advised against it. Francis then replaced Charles with his brother-in-law, Archduke Ferdinand, who was not very experienced.

Mack was put in charge of daily decisions, but he was also not well-suited for the job. When Mack was injured early in the campaign, command went to Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, a good cavalry officer but new to leading such a large army.

The Road to Ulm

The fighting in the upper Danube valley started in October. On October 8, near Wertingen, French cavalry and grenadiers surprised an Austrian force. The Austrians were caught off guard and couldn't form their defenses quickly enough. Nearly 3,000 Austrians were captured. A day later, at Günzburg, French troops chased two large Austrian groups towards Ulm.

The Austrians did have one small success at Haslach. On October 11, General Johann von Klenau set up his 25,000 soldiers in a strong defensive spot. An overconfident French general, Pierre Dupont de l'Étang, attacked with fewer than 8,000 men. The French lost 1,500 men and had some of their flags captured.

However, this was a rare win for the Austrians. On October 14, Mack sent two columns out of Ulm. One went towards Elchingen to secure a bridge, and the other went north. Marshal Michel Ney quickly moved his French troops to meet Dupont. The French attacked Elchingen, capturing a key abbey. The Austrians lost many men and artillery.

Napoleon's fast campaign showed how disorganized the Austrian army was. Mack had misunderstood where the French were and spread his forces too much. The French defeated each Austrian unit separately. By October 16, Napoleon had surrounded Ulm with 80,000 men. Karl Mack surrendered his army of 20,000 infantry and 3,273 cavalry.

Leading Up to the Battle

The few Austrian groups that weren't trapped at Ulm retreated towards Vienna, with the French close behind. A Russian army, led by General Mikhail Kutuzov, also moved away from the French, heading east. On October 22, they met up with the retreating Austrian soldiers. On November 5, the Coalition forces fought a successful rear-guard action at Amstetten. By November 8, the Russians had crossed the Danube river and destroyed the bridges behind them.

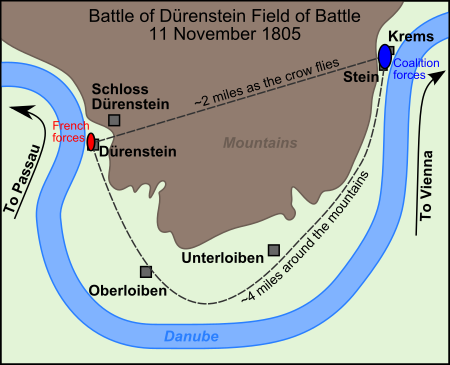

The Battlefield at Dürenstein

The town of Dürenstein is located where the Danube river makes a big curve. This creates a crescent-shaped flat area between the river and the mountains. At one end of this flat area, the mountains come very close to the river, and that's where Dürenstein and its old castle, Schloss Dürenstein, are located. This castle was once a prison for Richard I of England in 1193! The mountains here have narrow canyons and steep, rocky slopes.

The area was famous for its wine, with vineyards built on terraces up the hillsides. Because of the mountains and steep slopes, you couldn't see clearly from one end of the battlefield to the other.

Troop Positions Before the Battle

Napoleon thought Kutuzov would retreat towards Vienna, hoping for a big battle there. So, Napoleon created a new VIII Corps to secure the north side of the Danube. This corps, known as Corps Mortier, was led by Édouard Mortier. It was supposed to stop Austrian or Russian groups from joining up and prevent Kutuzov from escaping to Russia.

Mortier's corps had three infantry divisions and a cavalry division. They crossed the Danube in early November and marched east. General Gazan's division (about 6,000 men) was in the lead, with Mortier himself. Dupont's division (4,000 men) was about a day's march behind, and Dumonceau's division (4,000 men) was another day behind Dupont.

On November 9, Gazan's division reached Dürenstein and pushed back some Russian patrols. Mortier set up his command post there. However, Mortier made a mistake: he didn't protect his left (north) side, even though Napoleon had told him to. This was a big problem because the French cavalry, which usually scouted ahead, had gone off in another direction. Mortier and Gazan were marching blindly into the narrow canyon west of Dürenstein.

What they didn't know was that Kutuzov had already crossed the Danube at Krems, just past Stein, and destroyed the bridge. This cut off a possible escape route for the French. Kutuzov had also gathered about 24,000 Russian and Austrian soldiers very close to the French position. Gazan's division only had 6,000 men. The Coalition force included infantry, Jägers (skilled skirmishers), musketeers, cavalry, and over 68 cannons. The Russian Cossacks were excellent at patrolling the riverbanks.

On the evening of November 10, Kutuzov held a meeting with his generals. He knew the French positions and how spread out they were, thanks to prisoners captured by his Cossacks. He also knew that Gazan was far ahead of any French reinforcements. Kutuzov, who had learned from the famous Russian General Suvorov, decided to set a trap.

The Battle Plan

The plan was to surround the French at Dürenstein. Russian General Mikhail Miloradovich would attack Gazan's division from the east, pinning them in place. Three more columns, led by Dmitry Dokhturov, Major General Strik, and the Austrian General Johann Heinrich von Schmitt, would attack the French from the west and north.

They spread a rumor that the Russian army was retreating into Moravia, leaving only a small group behind at Krems. This was the bait for Mortier.

The Battle Begins

On the night of November 10–11, Strik's Russian column began moving through the narrow canyons, aiming to reach Dürenstein by noon. Two other columns, under Dokhturov and Schmitt, took wider routes through the mountains to attack the French from the sides. The plan was for Strik to attack first, from the mountains, hitting the French right side. This attack, combined with Miloradovich's attack from the front, would trap the French. Even if the French tried to retreat west, they would be caught.

Mortier fell for the rumor of a Russian retreat. Early on November 11, he and Gazan left Dürenstein to capture Stein and Krems, thinking only a small Russian group was left. As they neared Stein, Miloradovich's troops attacked. Mortier thought this was just the small rear guard and ordered Gazan to counterattack.

The fighting spread through the villages of Oberloiben, Unterloiben, and the farm at Rothenhof. Instead of retreating, more and more Russian soldiers appeared.

Gazan's troops made good progress at first, but they soon realized they were facing a much larger force. Mortier realized he had been tricked. He sent orders for Dupont's division to hurry forward. By mid-morning, the French attack had slowed down. Mortier used most of his remaining troops to push Miloradovich back, leaving only about 300 soldiers to guard his northern side. He then attacked the Russian right. He gained a numbers advantage for a short time, with 4,500 French against 2,600 Russians, pushing them back towards Stein. Miloradovich had no choice but to retreat, as Strik's or Dokhturov's flanking columns had not yet arrived.

The fighting paused. Mortier and Gazan waited for Dupont, while Kutuzov and Miloradovich waited for Strik and Dokhturov. Strik's column arrived first and immediately attacked Gazan's line, pushing the French out of Dürenstein. Caught between two strong forces, Gazan tried to fight his way back through Dürenstein to reach the river, hoping his tired troops could be evacuated by boat.

As Gazan's division retreated through the narrow Danube canyon, fighting off the Russians behind them, they were trapped when more of Strik's Russians blocked their path. The narrow canyons made it hard for the Russians to attack in large groups. Despite Strik's constant attacks for the next two to three hours, Mortier and Gazan pushed the Russians back up the hillside. At this point, Dokhturov's column appeared behind the French line and joined the battle. The French were now outnumbered more than three to one, attacked from the front by Miloradovich, in the middle by Strik, and from the rear by Dokhturov.

Earlier that morning, Dupont had been marching his column along the river from Marbach. Even before Mortier's message arrived, he heard the sound of cannons. He sent riders ahead who reported that a Russian column (Dokhturov's) was coming down from the mountains towards Dürenstein. Realizing this would cut him off from the main French division, Dupont quickly moved his troops towards the sound of the battle. His attack, with cannon fire, made Dokhturov's troops turn from Gazan's struggling force to face this new threat. Dokhturov's column had more soldiers, but no supporting cannons, and the narrow space prevented them from using their numbers effectively. Now it was Dokhturov's turn to face attacks from both front and rear, until Schmitt's column arrived.

Schmitt arrived at dusk, and the battle continued long after dark. In mid-November, night falls early in this part of Austria. Despite the darkness, Schmitt's troops came down from the mountains and attacked Dupont's side. As his Russians joined the fight, they got mixed up with French and other Russian soldiers. The French were overwhelmed, but much of the shooting stopped because it was too dark to tell who was who. Under the cover of darkness, Mortier used the French boats to move his exhausted troops to the south bank of the river. The French and Russians continued to fight in small skirmishes throughout the night. The next morning, the remaining French soldiers were evacuated from the north side of the Danube.

Who Won and Who Lost?

The losses were huge for both sides. Gazan's French division lost almost 40% of its men killed or wounded. They also lost five cannons and many soldiers were captured, bringing their total losses to about 60%. They even lost some important flags, including the French Imperial Eagle. The Russians lost around 4,000 men, about 16% of their force, and two regimental flags. The Austrian General Schmitt was killed at the end of the battle, likely by Russian gunfire in the dark and confused fighting.

The villages of Ober- and Unterloiben were destroyed, as were most of Dürenstein and Stein. Krems was also badly damaged.

What Happened Next?

Both sides claimed victory. Even though the number of dead or wounded was similar (around 4,000 on each side), the Coalition forces started with 24,000 men, while the French began with Gazan's 6,000, growing to about 8,000 when Dupont arrived. Gazan's division was almost completely destroyed. The fighting was very tough, and the weather was cold with icy mud.

For the Coalition, the Russians were safe on the north bank of the Danube, waiting for more troops. The destroyed bridges made it harder for the French to reach Vienna. After months of bad news for the Austrians, this battle was a much-needed victory. The French had retreated with a badly damaged division. Emperor Francis was so happy that he gave Kutuzov a special award.

For the French, it seemed like a miracle that Mortier's corps survived. The rest of Gazan's division crossed the river the next morning and later recovered in Vienna, which the French captured by trickery later that month. The French soldiers had fought very well in difficult conditions. While some French soldiers panicked and tried to escape on boats that crashed, most of Gazan's troops stayed together and fought bravely. Dupont showed great skill by rushing his troops to help when he heard the cannons.

After the big victory at Austerlitz, Napoleon broke up the VIII Corps and gave Mortier a new assignment. Napoleon was very pleased with Gazan's performance. For his bravery in what the French called "the immortal Battle of Dürenstein," Gazan received a high honor, the Officer's Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour.

The death of General Schmitt was a big loss for the Austrian army. He was their most experienced staff officer, second only to Archduke Charles. He was a trusted advisor and had helped plan many important Austrian victories. Without Schmitt, the plan for the Battle of Austerlitz was developed by Franz von Weyrother, who had been responsible for a major Austrian defeat in 1800. Schmitt would likely have created a more realistic plan for Austerlitz. While his presence might not have changed the outcome, it could have reduced the huge losses for the Coalition. Austerlitz is considered one of Napoleon's greatest triumphs.

Overall, the War of the Third Coalition was decided on land. Despite some small Austrian successes, like at Haslach-Jungingen, and some troops escaping the French encirclement at Ulm, the Austrians suffered heavy losses. The victories at Dürenstein and Schöngrabern were the only bright spots for Austria that autumn. In the end, Austria lost an entire army and many officers.

The decisive French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz forced Austria to leave the Coalition. The Peace of Pressburg, signed on December 26, 1805, made Austria give up land to Napoleon's German allies and pay a large sum of money. This victory also allowed Napoleon to create a group of German states called the Confederation of the Rhine, which acted as a buffer zone between France and other major powers. However, this peace didn't last long, as Prussia's worries about French influence led to the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806.

Remembering the Battle

Before 1805, Dürenstein was mostly known as the place where Crusader Richard the Lionheart was held prisoner. In 1741, during another war, local villagers famously tricked French and Bavarian armies by painting drain pipes to look like cannons and beating drums, making the enemy think there was a huge force defending the town.

After 1805, the story of the 40,000 French, Russian, and Austrian soldiers fighting at Dürenstein captured people's imaginations. General Schmitt's grave was never found, but a monument for him was built in 1811 at the Stein Tor in Krems. The house of Captain von Stiebar, who helped with local geography, was marked with a bronze plate.

In 1840, a Spanish artist created a picture of the battle, showing French troops being evacuated by boat on a moonlit night. However, the moon wasn't that bright on November 11. A French historical painter, Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort, also created a watercolor of the battle in 1836.

The famous Russian novel War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy includes several pages about the Battle of Dürenstein. Between Dürenstein and Rossatz, there is a monument called the "Little Frenchman" memorial, built in 1905, to remember the battle. It has the names of important leaders like Mortier, Gazan, Kutuzov, and Schmitt.

Armies in Battle

French VIII. Corps (Corps Mortier)

On November 6, Édouard Adolphe Mortier commanded these forces:

- 1st Division: Led by Pierre Dupont de l'Étang, with six battalions, three cavalry squadrons, and three cannons. Most of these troops joined the fighting in the afternoon.

- 2nd Division: Led by Honoré Théodore Maxime Gazan de la Peyrière, with nine battalions, three cavalry squadrons, and three cannons.

- 3rd Division: Led by Jean-Baptiste Dumonceau (the Batavian Division). This division did not take part in the battle.

- Dragoon Division: Led by Louis Klein, including four regiments of dragoons. These cavalry units were not involved in the fighting.

- Danube fleet: Fifty boats, commanded by Frigate Captain Lostange.

In total, the French had about 12,000 men, but not all of them fought in the battle.

Coalition Forces

The Coalition army was made up of several columns:

- First Column: Led by General Prince Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration, with infantry, grenadiers, Jägers (light infantry), and Hussar cavalry.

- Second Column: Led by Lieutenant General Essen, with infantry, grenadiers, and Hussar cavalry.

- Third Column: Led by Lieutenant General Dokhturov, with infantry, Jägers, and Hussar cavalry.

- Fourth Column: Led by Lieutenant General Schepelev, with nine battalions of infantry.

- Fifth Column: Led by Lieutenant General Freiherr von Maltitz, with nine battalions of infantry.

- Sixth Column: Led by Lieutenant General Freiherr von Rosen, with infantry and cavalry. This column did not fight in the battle.

- Austrian Infantry Brigade: Led by Major General Johann Nepomuk von Nostitz-Rieneck, with four battalions of Border Infantry.

- Austrian Cavalry Division: Led by Lieutenant Field Marshal Friedrich Karl Wilhelm, Fürst zu Hohenlohe, with twenty-two squadrons of cavalry.

In total, the Coalition had about 24,000 men and 168 cannons.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |