Battle of Edson's Ridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Edson's Ridge |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theatre of World War II | |||||||

An American Marine stands near some of the fighting positions on Hill 123 on "Edson's" Ridge after the battle. Edson's command post during the battle was located just to the right of where the Marine is standing. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,500 | 6,217 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 59 killed or missing 204 wounded |

700–850 killed ~500 wounded |

||||||

The Battle of Edson's Ridge was a major land battle during World War II. It took place from September 12 to 14, 1942, on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. This battle was a key part of the larger Guadalcanal campaign.

In this fight, U.S. Marines faced off against the Imperial Japanese Army. The Marines, led by Major General Alexander Vandegrift, defended a vital airfield called Henderson Field. The Japanese, under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, tried to recapture the airfield.

The main Japanese attack focused on a narrow ridge south of Henderson Field. This ridge was defended by U.S. Marines, especially the 1st Raider and 1st Parachute Battalions. These units were led by Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson. Even though the Japanese attacked fiercely at night, the Marines held their ground. The Japanese suffered heavy losses and failed to take the airfield.

Because Edson's unit played such a crucial role, the ridge became known as "Edson's Ridge." This battle was a big defeat for the Japanese. It forced them to change their war plans in other parts of the South Pacific.

Contents

Why was Guadalcanal Important?

The Start of the Campaign

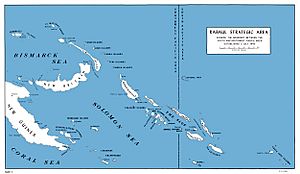

On August 7, 1942, Allied forces, mainly from the U.S., landed on Guadalcanal and nearby islands. Their goal was to stop Japan from using these islands as military bases. These bases could threaten important supply routes between the U.S. and Australia. The Allies also wanted to use the islands as a starting point to attack a major Japanese base at Rabaul. This marked the beginning of the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.

The Allies surprised the Japanese. By August 8, they had secured the islands of Tulagi and Gavutu. They also captured an airfield that was being built at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. This airfield was later named Henderson Field. It was named after Major Lofton R. Henderson, a Marine pilot killed at the Battle of Midway. The planes and pilots flying from Henderson Field were called the "Cactus Air Force."

Japan's Response to the Landings

Japan's military leaders ordered the 17th Army to retake Guadalcanal. This army was based at Rabaul and led by Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake. However, the 17th Army was already busy fighting in New Guinea. So, they had only a few units available to send to the Solomon Islands.

One of these units was the 35th Infantry Brigade under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. Another was the 28th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki. Ichiki's regiment was the closest. About 917 of his soldiers landed on Guadalcanal on August 19.

Ichiki's troops attacked the Marines on August 21. They thought there were fewer Allied soldiers than there actually were. This attack, known as the Battle of the Tenaru, was a disaster for Japan. Almost all of Ichiki's 917 men were killed. Only 128 survived.

The "Tokyo Express"

After this defeat, Japan decided to send more troops. However, Allied air attacks made it dangerous to use slow transport ships. So, the Japanese began using fast destroyers to bring soldiers to Guadalcanal. These high-speed trips happened at night to avoid Allied planes. The Allies called these runs the "Tokyo Express." The Japanese called them "Rat Transportation."

These destroyers could bring soldiers, but not heavy equipment like artillery or large amounts of food. This meant Japanese soldiers often arrived without enough supplies. The Japanese controlled the seas at night. But any Japanese ship near Henderson Field during the day was in great danger from Allied aircraft.

On August 28, some Japanese destroyers carrying Kawaguchi's troops were attacked by U.S. dive bombers. One destroyer was sunk, and two were damaged. This attack killed 62 Japanese soldiers. However, other "Tokyo Express" runs were more successful. Between August 29 and September 4, nearly 5,000 Japanese troops landed on Guadalcanal. General Kawaguchi took command of all Japanese forces on the island.

Kawaguchi also tried to send troops by slow barges. But these barges were attacked by planes from Henderson Field. About 90 soldiers died, and much heavy equipment was lost. By September 7, Kawaguchi had about 5,200 troops at Taivu Point and 1,000 more to the west. He thought there were only about 2,000 U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal. This was a big mistake.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Marines were making their defenses stronger. Between August 21 and September 3, about 1,500 more Marines arrived on Guadalcanal. These included Edson's Raiders and the 1st Parachute Battalion.

The Battle Begins

Preparing for the Attack

Kawaguchi planned his attack on the Lunga perimeter for September 12. He asked for air strikes on Henderson Field and naval ships to shell the area. His plan was to split his forces into three groups. They would approach the Marine defenses from inland and launch a surprise night attack.

Kawaguchi's main force, about 3,000 men, would attack from the south. Other units would attack from the east and west. On September 7, most of Kawaguchi's troops began marching towards Lunga Point. About 250 Japanese soldiers stayed behind to guard supplies.

Meanwhile, native island scouts told the Marines about Japanese troops at Taivu. This was about 17 miles (27 km) east of the Marine perimeter. Edson decided to launch a raid against them. On September 8, 813 of Edson's men landed at Taivu. They were supported by planes and gunfire from ships.

Edson's Marines pushed into the village of Tasimboko. The Japanese defenders retreated into the jungle. The Marines found a large supply base for Kawaguchi's forces. It had lots of food, ammunition, and medical supplies. They also found a radio and important documents. The Marines took what they could, destroyed the rest, and returned to their base. The documents showed that at least 3,000 Japanese troops were on the island and planning an attack.

Edson and Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, a Marine operations officer, believed the Japanese would attack the Lunga Ridge. This ridge was a narrow, grassy area about 1,000 yards (910 m) long. It was south of Henderson Field and was a natural path to the airfield. It was also almost undefended. Edson and Thomas convinced General Vandegrift to move Edson's Raiders to defend the ridge. On September 11, 840 of Edson's men took up positions on and around the ridge.

Kawaguchi's main force was indeed planning to attack the ridge. They called it "the centipede" because of its shape. On September 9, Kawaguchi's troops began marching through the thick jungle. They had poor maps and some compasses didn't work. This made their march slow and difficult.

The First Night's Fight (September 12)

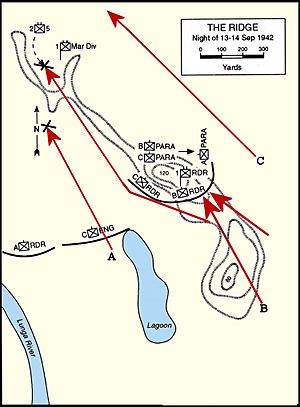

The Marines knew the Japanese were coming but not exactly where or when. Edson placed his men on three hills along the ridge. Hill 80 was at the southern end. Hill 123, the tallest, was 600 yards (550 m) north. Edson's command post was on Hill 123.

At 9:30 PM on September 12, Japanese ships shelled the Marine lines. Then, Japanese artillery began firing. Scattered groups of Japanese soldiers started fighting with the Marines. Kawaguchi's 1st Battalion attacked the Raiders' Company C. They pushed the Marines back towards the ridge.

This attack got mixed up with another Japanese unit that was still trying to reach its position. This confusion stopped the Japanese attack for the night. Kawaguchi later said he felt "disappointed and helpless" because the jungle scattered his brigade. Twelve Marines were killed. Japanese casualties were likely higher. Other Japanese units also tried to attack that night but failed to reach the Marine lines.

At dawn on September 13, Allied planes and Marine artillery fired into the area south of the ridge. This forced Japanese soldiers to hide. Kawaguchi decided to regroup his forces for another attack that night.

The Second Night's Fight (September 13-14)

Knowing the Japanese would attack again, Edson ordered his troops to improve their defenses. He pulled his front line back about 400 yards (370 m) to a strong position around Hill 123. Any Japanese attackers would have to cross 400 yards of open ground to reach the Marines. The Marines had little time to build strong defenses. They were also low on ammunition and grenades.

Edson gave a speech to his tired troops. He asked them to "Hold out just one more night." He promised they would get relief in the morning. His words boosted their spirits.

As the sun set on September 13, Kawaguchi's 3,000 troops faced Edson's 830 Marines. The night was very dark. At 9:00 PM, Japanese destroyers briefly shelled the ridge. Kawaguchi's attack began shortly after.

One Japanese battalion attacked the Marine right side. They pushed the Marines back to Hill 123. Instead of attacking other Marine units, these Japanese soldiers found a pile of Marine supplies. They stopped to eat, as they hadn't eaten properly for days. They later continued their attack towards the airfield but were stopped. Their commander and about 100 men were killed.

Meanwhile, another Japanese battalion attacked Hill 80. Marine artillery fired on their positions. Around 10:00 PM, about 320 Japanese soldiers charged up Hill 80 with bayonets. They pushed some Marines off the ridge. Edson ordered other Marines to pull back onto Hill 123.

In the darkness, some Marines became confused and started to retreat. But Marine officers, including Major Kenneth D. Bailey, stopped them. They used strong words to get the Marines back into position around Hill 123.

As the Marines formed a horseshoe shape around Hill 123, the Japanese launched many direct attacks. They charged up the hill repeatedly. Japanese planes dropped flares to light up the area. The Marines fought back with rifles, machine guns, mortars, and grenades. Marine artillery also caused heavy losses for the Japanese. One captured Japanese soldier said his unit was "annihilated" by the artillery.

The fighting was intense, with hand-to-hand combat. Japanese snipers fired from all sides. Edson stood about 20 yards (18 m) behind the firing line on Hill 123. He encouraged his troops and directed their defense. One Marine said Edson "held a battalion together" that night.

Some Japanese units managed to get past the Marine defenses. They reached the edge of a secondary runway at Henderson Field. But Marine engineers stopped one group. The others waited for reinforcements that never came. They eventually retreated back into the jungle.

By 4:00 AM, Edson's men had held off many attacks. Troops from another Marine battalion arrived to help. As the sun rose on September 14, the Japanese attack on the ridge had ended. Many Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded. About 100 Japanese soldiers remained on Hill 80. U.S. planes strafed them, killing most of them. The few survivors retreated.

Other Japanese Attacks

While the main battle happened on the ridge, other Japanese units also attacked the Marine defenses. The Kuma battalion attacked the southeastern part of the Marine lines. Their attack started around midnight. One company fought hand-to-hand with Marines but was pushed back. Their commander was killed.

The next morning, Marines sent light tanks to sweep the area. Japanese anti-tank guns destroyed three of them. Some tank crewmen escaped but were killed by Japanese soldiers. The Kuma battalion made two more "weak" attacks on September 14 and 15, but both failed.

Another Japanese unit, Oka's, attacked the western side of the Marine perimeter. Two Japanese companies attacked around 4:00 AM on September 14. They were pushed back with heavy losses. Another company captured a small ridge but was pinned down by Marine artillery all day. They suffered heavy losses before retreating. The rest of Oka's unit couldn't find the Marine lines and didn't join the attack.

What Happened Next?

On September 14, Kawaguchi led the survivors of his brigade away from the ridge. They went deeper into the jungle to rest and care for their wounded. They were ordered to march west to the Matanikau River valley. This was a 6-mile (10 km) march over very difficult land.

Kawaguchi's troops started marching on September 16. Many soldiers had to carry the wounded. They were exhausted and hungry. They began to throw away their heavy equipment and even their rifles. By the time they reached their destination five days later, only half still had their weapons. Some survivors got lost and wandered for three weeks before finding the camp.

In total, Kawaguchi's forces lost about 830 men killed in the attack. The Marines counted 500 Japanese dead on and around the ridge. The Marines lost 80 killed between September 12 and 14.

After the battle, the U.S. forces focused on making their defenses stronger. On September 14, another Marine battalion arrived on Guadalcanal. On September 18, over 4,000 more Marines arrived. These reinforcements allowed General Vandegrift to create a continuous line of defense around the Lunga perimeter. The next major battles between the U.S. and Japanese happened along the Matanikau River later in September and October.

Why This Battle Mattered

On September 15, General Hyakutake in Rabaul learned of Kawaguchi's defeat. This was the first time a Japanese unit of this size had been defeated in the war. Japanese military leaders decided that Guadalcanal might become "the decisive battle of the war."

The outcome of Edson's Ridge had a big impact on Japan's war plans. Hyakutake realized he couldn't send enough troops to Guadalcanal and continue a major attack in New Guinea at the same time. So, he ordered his troops in New Guinea to stop their advance. They were very close to their goal of Port Moresby. The Japanese were never able to restart their attack on Port Moresby.

The defeat at Edson's Ridge helped lead to Japan's overall defeat in the Guadalcanal campaign. It also contributed to Japan's ultimate defeat in the entire South Pacific. General Vandegrift later said that Kawaguchi's attack on the ridge was the only time he doubted the outcome of the campaign. He believed that if the Japanese had succeeded, the Marines would have been in a "pretty bad condition." Historian Richard B. Frank wrote that the Japanese "never came closer to victory on the island itself than in September 1942."

Today, at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego, new Marine recruits finish their training with a tough 54-hour final test called "The Crucible." In the last part, they climb a mountain called The Reaper. At the top, a quote from Edson's Medal of Honor award is displayed. Recruits read it and learn about it. Then, they receive their Eagle, Globe and Anchor emblems, which means they are officially Marines.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |