Battle of Honsinger Bluff facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Honsinger Bluff |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Lakota | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Rain in the Face | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 7th United States Cavalry | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~200 Warriors | ~91 Soldiers, 4 Civilians | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 wounded | 3 killed, 1 wounded | ||||||

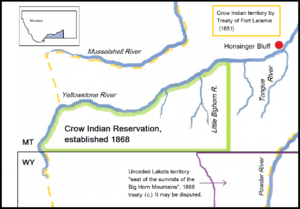

The Battle of Honsinger Bluff was a fight between the United States Army and the Sioux people. It happened on August 4, 1873. The battle took place along the Yellowstone River in what is now Miles City, Montana. This land had become U.S. territory in 1868, after being acquired from the Crow tribe.

The main groups fighting were the U.S. 7th Cavalry, led by George Armstrong Custer, and Native American warriors. These warriors were from the village of Hunkpapa medicine man, Sitting Bull. Many of these same warriors would later fight Custer again. This happened about three years later at the famous Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Contents

Where the Battle Happened

The Battle of Honsinger Bluff took place about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of where the Tongue River meets the Yellowstone River. The battlefield was on a flat area next to the Yellowstone River. A large gravelly hill, known as "Big Hill" or "Yellowstone Hill," was important to the area. This hill is very long, about 13 miles (21 km), and has steep sides. Today, the Miles City Airport is located on this hill.

To the east and south of the battlefield is the Yellowstone River. The flat area, or floodplain, stretches west along the Yellowstone for about 13 miles (21 km). Key spots during the battle included Honsinger Bluff itself, which was on the side of Yellowstone Hill. There were also two large groups of cottonwood trees along old parts of the Yellowstone River.

History of the Battlefield Area

In 1851, the land where the battle would later happen became part of a treaty. The Treaty of Fort Laramie said this area was Crow Indian country. The Lakota tribe also recognized this. Many battles in the 1860s and 1870s between the U.S. Army and the Lakota happened on lands the Lakota had taken from other tribes since 1851.

On May 7, 1868, the Crow tribe agreed to live on a smaller reservation. Because of this, all the 1851 Crow treaty land north of the Yellowstone River became U.S. territory. This included the future site of Honsinger Bluff.

Who Fought in the Battle?

U.S. Army Forces

George Armstrong Custer and parts of the 7th Cavalry were part of a larger military group. This group was led by Colonel David S. Stanley. They were protecting a survey team for the Northern Pacific Railway in 1873. This team was mapping the north side of the Yellowstone River.

Stanley's group had about 1,300 soldiers, including cavalry and infantry. They also had two cannons. They traveled with 275 wagons and 353 civilians who were part of the survey. About 27 Native American and mixed-blood scouts also helped the column.

Native American Forces

The Native American warriors came from Sitting Bull's village. This village was located nearby and had about 400 to 500 lodges (homes). The warriors included Hunkpapa Sioux led by Gall and the war chief Rain in the Face. There were also Oglala Sioux under Crazy Horse, and warriors from the Miniconjou and Cheyenne tribes.

Leading Up to the Battle

On August 3, 1873, Stanley's main group camped near Sunday Creek. Early on August 4, the group moved along the northwest side of Yellowstone Hill. Captain George W. Yates and his cavalry troop went with the surveyors along the Yellowstone River.

Custer, with two companies of the 7th Cavalry, rode ahead to scout the area. His group had 86 men, 5 officers, and some Native American scouts. Custer's brother, Lieutenant Tom Custer, and his brother-in-law, Lieutenant James Calhoun, were with him.

Custer's troops rode along the top of Yellowstone Hill. Then they went down a steep path to a wide, grassy plain. Custer saw a wooded area by the Yellowstone River, about 2 miles (3.2 km) to the west. He thought it would be a good place for Stanley's main group to camp later. Custer's men rested in the woods, napping and fishing. Their horses grazed in the grass nearby. Feeling that danger might be near, Custer set up two small guard patrols.

Meanwhile, scouts from Sitting Bull's village were also moving along the Yellowstone River. They did not seem to know about Stanley's main group. However, they did spot Custer's group resting in the woods. More warriors came from Sitting Bull's village. By noon, between 100 and 300 Native American warriors were hiding in another wooded area, about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Custer's location.

The Battle Begins

The Decoy Tactic

A small group of Native American warriors rode towards the cavalry's grazing horses from the west. Custer's guards saw them and warned the other soldiers. Custer ordered his men to get ready. He began to chase the riders with his orderly and Lieutenant Calhoun. Tom Custer followed with about 20 soldiers. The rest of Custer's unit followed behind.

Custer stopped his chase, and the Native American riders also stopped. When he moved, they moved. They were heading towards the wooded area where the larger group of warriors was hiding. This was a trick similar to one used in the Fetterman Massacre in 1866. As Custer got closer to the woods, the hidden warriors, estimated to be 100 to 300 strong, burst out and chased Custer.

Custer rode back through a line of soldiers formed by Tom Custer's men. The shots from this line of soldiers surprised the chasing warriors, making them stop their charge. Custer then had his men pull back to the wooded area they had been resting in.

The Cavalry Under Siege

Once in the wooded area, the cavalry soldiers got off their horses. They formed a half-circle defense line along an old, dry river channel. Usually, one soldier would hold four horses, but because their line was so long, one soldier had to hold eight horses. The bank of the dry channel gave them some natural protection.

The Native American forces surrounded the cavalry troops, but their attacks had little effect. About an hour into the battle, nearly 50 warriors tried to go around the cavalry's defense line by moving along the river. They were hidden by the high river bank. However, a scout with them was seen and drew fire. Thinking they had been discovered, the group retreated.

Since going around the side didn't work, the warriors set the grass on fire. They hoped the smoke would hide them as they got closer to the cavalry. But Custer's troops also used the smoke to move closer to the warriors. So, the fire didn't give either side a clear advantage. The fighting continued for about three hours in very hot weather, reportedly 110°F (43°C).

The Ambush of Dr. Honsinger

Dr. John Honsinger was the 7th Cavalry's main veterinarian. He was riding with Stanley's main group. Around 2:00 p.m., Dr. Honsinger and a civilian named Augustus Baliran left Stanley's group. They wanted to water their horses and look for interesting rocks by the river. They didn't know a battle was happening a few miles away.

A scout from the Stanley group tried to stop Dr. Honsinger. The scout pointed west and said "Indians, Indians." Dr. Honsinger heard some shooting in that direction. He thought it was Custer's men hunting. So, he said "Cavalry, Cavalry" and rode on.

At the same time, two soldiers, Privates John H. Ball and M. Brown, left their company. They went to the river to cool off. Private Ball saw Honsinger and Baliran and rode to join them.

Meanwhile, Rain in the Face and five warriors went to the base of Yellowstone Hill, now called Honsinger Bluff. They were there to watch for any approaching cavalry. They saw Honsinger and Baliran coming. They hid among the rocks and bushes. They were so well hidden that they were able to grab Honsinger's horse as he rode by. Dr. Honsinger was pulled from his horse and died. Baliran and Ball also died quickly from Rain in the Face and his men.

The Cavalry Charge

The Native American forces surrounded Custer's troops for a long time, which was unusual. Most fights were much shorter. Custer's men were running low on ammunition. They asked the soldiers holding the horses for more supplies. Towards the end of the battle, due to the extreme heat, the shooting became very slow. At this point, Custer ordered his men to get on their horses, and the bugler sounded the charge.

Private Brown, who had been resting near Honsinger's Bluff, woke up and saw the ambush of Honsinger and Baliran. He also saw Private Ball trying to escape. Brown quickly got on his horse without a saddle. He rode fast towards Stanley's main group. Stanley heard the shots and saw Private Brown riding wildly, yelling that everyone down there was killed. Fearing another disaster like the Fetterman Massacre, Stanley sent the rest of the 7th Cavalry forward.

When the cavalry arrived at Honsinger Bluff, they had to get off their horses to go down the steep slope. As they got back on their horses, Rain in the Face's group rode past them, heading back towards the main Native American force.

Custer's mounted soldiers burst from the woods in a charge. This scattered the Native American forces, who fell back upriver. Custer's troops chased them for nearly four miles but could not catch them to fight closely. Historians still discuss whether Custer charged on his own or if he saw the reinforcements coming and planned his charge with their arrival.

Casualties

Custer's 7th Cavalry reported one man wounded and two horses killed in Custer's official report. However, the 7th Cavalry lost three men: Dr. John Honsinger, Augustus Baliran, and Private Ball. Honsinger and Baliran were found the day of the battle. Private Ball's body was found later in September 1873.

No bodies of Native American warriors were found on the battlefield. However, it was estimated that about five warriors died, and many others, along with their horses, were wounded.

What Happened After

Rain in the Face kept Honsinger's gold watch. He later spoke about his role in the deaths of Honsinger and Baliran. Custer heard about Rain in the Face's claims. He sent his brother, Tom Custer, to the Standing Rock Reservation to arrest him. Rain in the Face was arrested and jailed on December 13, 1874. However, he escaped a few months later. He then vowed to harm Tom Custer.

Lieutenant Charles Braden was badly wounded a week later, on August 11, 1873. This happened in another fight with Sitting Bull's forces near the Big Horn River. He was hit in the thigh by a bullet and had to retire from the Army in 1878.

George Armstrong Custer, Tom Custer, and James Calhoun, along with Captain George Yates, all died at the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. Myles Moylan and Charles Varnum survived that battle. Moylan later received a special award for his bravery in the Battle of Bear Paw in 1877. In that battle, U.S. forces captured the Nez Perce band led by Chief Joseph.

Sitting Bull, Gall, Crazy Horse, and Rain in the Face all took part in the Little Bighorn battle. In later years, Rain in the Face claimed to have harmed Tom Custer at Little Bighorn.

Dr. John Honsinger was buried along the Yellowstone River at Honsinger Bluff. Some stories say that Father Pierre DeSmet oversaw the burial. However, Father DeSmet had died in St. Louis on May 23, 1873. This was more than two months before the battle.

U.S. Army troops returned to this area on June 6 and 7, 1876. This was just before the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The Montana column, led by Colonel John Gibbon, camped a few miles west of Honsinger Bluff. This was likely one of the wooded areas used during the Battle of Honsinger Bluff.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |