Beijing cuisine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Beijing cuisine |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Chinese | 北京菜 | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Jing cuisine | |||||||

| Chinese | 京菜 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Cuisine of the capital | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Beiping cuisine | |||||||

| Chinese | 北平菜 | ||||||

|

|||||||

Beijing cuisine, also known as Jing cuisine, is the traditional food style from Beijing, the capital city of China. It's also called Mandarin cuisine or Peking cuisine. This food style has been shaped over many centuries.

Contents

What is Beijing Cuisine?

Beijing has been China's capital for a long time. This means its food has been influenced by many different cooking traditions from all over China. The biggest influence comes from Shandong Province, which is on the eastern coast. In return, Beijing cuisine has also greatly influenced other Chinese food styles, especially in Liaoning and the special foods made for Chinese emperors and rich families.

How Imperial Kitchens Shaped Beijing Food

A big part of Beijing cuisine comes from the "Emperor's Kitchen" (Chinese: 御膳房; pinyin: yùshànfáng). This was a huge cooking area inside the Forbidden City. Thousands of chefs from all over China worked there. They used their best skills to create amazing dishes for the emperor and his family. Because of this, it's sometimes hard to know where a Beijing dish truly started. The word "Mandarin" can mean food from Beijing, but also from other provinces.

Key Features of Beijing Dishes

However, we can still describe Beijing cuisine in some general ways:

- Many original Beijing foods are often snacks, not main meals.

- These snacks are usually sold by small shops or street vendors.

- Chefs often use dark soy paste, sesame paste, sesame oil, and green onions.

- Fermented tofu is often served as a side dish.

- Many cooking methods involve different ways of frying.

- Unlike other parts of China, rice is not as common as a main side dish. This is because Beijing's climate is quite dry, so not much rice grows there.

Influences from Other Regions

Many main dishes in Beijing cuisine come from Chinese Halal foods, especially lamb and beef dishes. Halal food follows Islamic dietary rules. Another important influence is Huaiyang cuisine. This food style has been famous in China for a long time. Officials moving to Beijing often brought their own chefs who specialized in Huaiyang cooking. When these officials left, many chefs stayed in Beijing. They opened their own restaurants or worked for wealthy locals.

The Ming dynasty imperial family also helped bring Huaiyang cuisine to Beijing. Their family came from Jiangsu Province. When the capital moved from Nanjing to Beijing in the 15th century, the imperial kitchen mostly cooked in the Huaiyang style. Even the tradition of enjoying Beijing opera while eating comes from the culture of Jiangsu and Huaiyang foods.

Chinese Islamic cuisine also played a big role, especially when Beijing became the capital during the Yuan dynasty. But the biggest influence on Beijing cuisine came from Shandong cuisine. Many chefs from Shandong Province moved to Beijing during the Qing dynasty. Unlike the earlier food styles, which were brought by rich rulers, Shandong cuisine became popular with everyone, from wealthy merchants to working-class people.

History of Beijing Cuisine

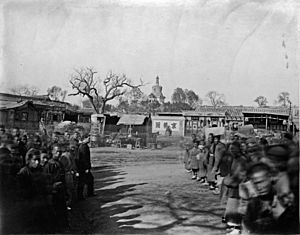

The Qing dynasty was a very important time for Beijing cuisine to develop. Before the Boxer Rebellion, restaurants and food places in Beijing had a strict ranking system. This system was set up by food service groups. Each type of place served a specific group of people. The best places served nobles, rich families, and wealthy merchants. Lower-ranked places served people with less money or lower social status.

During this time, Beijing cuisine became very famous in China. This strict ranking of food services was a key part of its food culture.

Changes After the Qing Dynasty

The official ranking system ended after the Qing dynasty. This led to a second big growth period for Beijing cuisine. Meals that were once only for nobles became available to anyone who could afford them. Chefs could move freely between different restaurants. This helped them share their skills, which made Beijing cuisine even richer and more developed. Even though the old laws were gone, some of the ranking structure remained, but it slowly became less strict.

Here are the different types of food establishments from that time, from highest to lowest rank:

Zhuang: Top-Tier Dining

Zhuang (simplified Chinese: 庄; traditional Chinese: 莊; pinyin: zhuāng; literally "village") or zhuang zihao (simplified Chinese: 庄字号; traditional Chinese: 莊字號; pinyin: zhuāng zìhào; literally "village brand") were the highest-ranked food places. They offered not just food but also entertainment, usually Beijing opera. These places had long-term deals with opera groups or famous performers. They only took group bookings for banquets, often filling most of their tables. A large part of their business was catering at people's homes for special events like birthdays, weddings, or funerals. They would even make special dishes if customers asked.

Leng zhuangzi (simplified Chinese: 冷庄子; traditional Chinese: 冷莊子; pinyin: lěng zhuāngzǐ; literally "cold village") were similar but only did catering, with no rooms for banquets.

Tang: Second-Class Establishments

Tang (Chinese: 堂; pinyin: táng; literally "auditorium") or tang zihao (simplified Chinese: 堂字号; traditional Chinese: 堂字號; pinyin: táng zìhào; literally "auditorium brand") were second-class places. Their business was split evenly between hosting banquets and catering. They also had opera troupes perform regularly, but not usually the most famous stars. For catering, they mostly stuck to their menu.

Ting: Foyer-Style Dining

Ting (simplified Chinese: 厅; traditional Chinese: 廳; pinyin: tīng; literally "foyer") or ting zihao (simplified Chinese: 厅字号; traditional Chinese: 廳字號; pinyin: tīng zìhào; literally "foyer brand") focused more on hosting banquets than catering. They still offered entertainment, but the performers changed often, and top stars rarely appeared. For catering, these places usually had to work together with other restaurants to handle big jobs.

Yuan: Garden Restaurants

Yuan (simplified Chinese: 园; traditional Chinese: 園; pinyin: yuán; literally "garden") or yuan zihao (simplified Chinese: 园字号; traditional Chinese: 園字號; pinyin: yuán zìhào; literally "garden brand") mostly hosted banquets at their own location. They had stages for Beijing opera performers, but these performers usually paid the restaurant to perform and then shared their earnings. These places sometimes helped with catering but never led the job.

Lou: Multi-Story Eateries

Lou (simplified Chinese: 楼; traditional Chinese: 樓; pinyin: lóu; literally "story, floor") or lou zihao (simplified Chinese: 楼字号; traditional Chinese: 樓字號; pinyin: lóu zìhào; literally "story brand") mainly hosted banquets by appointment. They also served walk-in customers. If they catered, they only provided a few of their most famous dishes.

Ju: Residence-Style Restaurants

Ju (Chinese: 居; pinyin: jū; literally "residence") or ju zihao (simplified Chinese: 居字号; traditional Chinese: 居字號; pinyin: jū zìhào; literally "residence brand") split their business between serving walk-in customers and hosting banquets for groups. Like the lou, they only offered their special dishes for catering. However, they might bring already-cooked food instead of always cooking on site.

Zhai: Study-Style Eateries

Zhai (simplified Chinese: 斋; traditional Chinese: 齋; pinyin: zhāi; literally "study") or zhai zihao (simplified Chinese: 斋字号; traditional Chinese: 齋字號; pinyin: zhāi zìhào; literally "study brand") mostly served walk-in customers. They also hosted some banquets by appointment. For catering, they would bring their famous dishes already cooked, only cooking on site sometimes.

Fang: Workshop-Style Shops

Fang (Chinese: 坊; pinyin: fǎng; literally "workshop") or fang zihao (simplified Chinese: 坊字号; traditional Chinese: 坊字號; pinyin: fǎng zìhào; literally "workshop brand") usually only served walk-in customers. They did not host banquets by appointment. These places and any lower-ranked ones were not called upon for catering special events.

Guan: General Restaurants

Guan (simplified Chinese: 馆; traditional Chinese: 館; pinyin: guǎn; literally "restaurant") or guan zihao (simplified Chinese: 馆字号; traditional Chinese: 館字號; pinyin: guǎn zìhào; literally "restaurant brand") mainly served walk-in customers. They also earned some money from selling food to go.

Dian: Shops

Dian (Chinese: 店; pinyin: diàn; literally "shop") or dian zihao (simplified Chinese: 店字号; traditional Chinese: 店字號; pinyin: diàn zìhào; literally "shop brand") had their own place, like the higher ranks. However, only half of their income came from customers dining in. The other half came from selling food to go.

Pu: Stores

Pu (simplified Chinese: 铺; traditional Chinese: 鋪; pinyin: pù; literally "store") or pu zihao (simplified Chinese: 铺字号; traditional Chinese: 鋪字號; pinyin: pù zìhào; literally "store brand") were second to last in rank. They often had the owner's last name in their name. These places had their own spots, but they were smaller than dian and only had seats, no tables. Most of their money came from selling food to go.

Tan: Food Stands

Tan (simplified Chinese: 摊; traditional Chinese: 攤; pinyin: tān; literally "stand") or tan zihao (simplified Chinese: 摊字号; traditional Chinese: 攤字號; pinyin: tān zìhào; literally "stand brand") were the lowest-ranked food places. They had no tables and only sold food to go. These stands were often named after the owner's last name or nickname, or after the food they sold.

Popular Beijing Dishes and Street Foods

Meat and Poultry Dishes

| English | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef wrapped in pancake | 門釘肉餅 | 门钉肉饼 | méndīng ròubǐng | |

| Beggar's Chicken | 富貴雞 | 富贵鸡 | fùguì jī | This dish's name means "rich chicken." It's also known as jiaohua ji. |

| Cold pig's ears in sauce | 拌雙脆 | 拌双脆 | bàn shuāngcuì | |

| Fried dry soybean cream with diced meat filling | 炸響鈴 | 炸响铃 | zhá xiǎnglíng | |

| Fried meatballs | 炸丸子 | 炸丸子 | zhá wánzǐ | |

| Fried wheaten pancake with meat and sea cucumber fillings | 褡褳火燒 | 褡裢火烧 | dālián huǒshāo | |

| Goat/sheep's intestine filled with blood | 羊霜腸 | 羊霜肠 | yáng shuāngcháng | |

| Hot and sour soup | 酸辣湯 | 酸辣汤 | suānlà tāng | |

| Instant-boiled mutton | 涮羊肉 | 涮羊肉 | shuàn yángròu | A type of hot pot where mutton is cooked in plain boiled water. |

| Lard with flour wrapping glazed in honey | 蜜汁葫蘆 | 蜜汁葫芦 | mìzhī húlú | |

| Lotus ham | 蓮棗肉方 | 莲枣肉方 | liánzǎo ròufāng | |

| Meatball soup | 清湯丸子 | 清汤丸子 | qīngtāng wánzǐ | |

| Meat in sauce | 醬肉 | 酱肉 | jiàngròu | |

| Moo shu pork | 木須肉 | 木须肉 | mùxūròu | Literally "wood shavings meat." |

| Napa Cabbage Hot pot | 酸白菜火鍋 | 酸白菜火锅 | suān báicài huǒguō | A hot pot from Northeast China with pickled cabbage and pork. |

| Peking barbecue | 北京烤肉 | 北京烤肉 | Běijīng kǎoròu | |

| Peking duck | 北京烤鴨 | 北京烤鸭 | Běijīng kǎoyā | Often served with thin pancakes. |

| Peking dumpling | 北京餃子 | 北京饺子 | Běijīng jiǎozǐ | |

| Peking wonton | 北京餛飩 | 北京馄饨 | Běijīng húndùn | |

| Pickled Chinese cabbage with blood-filled pig's intestines | 酸菜血腸 | 酸菜血肠 | suāncài xuěcháng | |

| Plain boiled pork | 白肉 | 白肉 | báiròu | |

| Pork in broth | 蘇造肉 | 苏造肉 | sūzào ròu | |

| Quick-fried tripe | 爆肚 | 爆肚 | bàodù | |

| Roasted meat | 燒肉 | 烧肉 | shāoròu | Can be beef, pork, or mutton. |

| Soft fried tenderloin | 軟炸里脊 | 软炸里脊 | ruǎnzhá lǐjī | |

| Stewed pig's organs | 燉吊子 | 炖吊子 | dùn diàozǐ | |

| Stir-fried tomato and scrambled eggs | 西紅柿炒雞蛋 | 西红柿炒鸡蛋 | xīhóngshì chǎo jīdàn | |

| Sweet and sour spare ribs | 糖醋排骨 | 糖醋排骨 | tángcù páigǔ | |

| Sweet stir-fried mutton / lamb | 它似蜜 | 它似蜜 | tāsìmì | |

| Wheaten cake boiled in meat broth | 滷煮火燒 | 卤煮火烧 | lǔzhǔ huǒshāo |

Fish and Seafood Dishes

| English | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abalone with peas and fish paste | 蛤蟆鮑魚 | 蛤蟆鲍鱼 | hāmǎ bàoyú | The name means "toad abalone." |

| Boiled fish in household-style | 家常熬魚 | 家常熬鱼 | jiācháng áoyú | |

| Braised fish | 酥魚 | 酥鱼 | sūyú | |

| Fish cooked with five kinds of sliced vegetable | 五柳魚 | 五柳鱼 | wǔlǐu yú | |

| Fish cooked with five-spice powder | 五香魚 | 五香鱼 | wǔxiāng yú | |

| Fish in vinegar and pepper | 醋椒魚 | 醋椒鱼 | cùjiāo yú | |

| Fish soaked in soup | 乾燒魚 | 干烧鱼 | gānshāo yú | |

| Sea cucumber with quail egg | 烏龍吐珠 | 乌龙吐珠 | wūlóng tǔzhū | The name means "the black dragon spits out pearls." |

| Shrimp chips with egg | 金魚戲蓮 | 金鱼戏莲 | jīnyú xìlián | The name means "the goldfish playing with the lotus." |

| Soft fried fish | 軟炸魚 | 软炸鱼 | ruǎnzhá yú |

Noodles (Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian)

| English | Image | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noodles with thick gravy |  |

打滷麵 | 打卤面 | dǎlǔmiàn | |

| Sesame Sauce Noodles |  |

麻醬麵 | 麻醬面 | májiàngmiàn | A popular noodle dish in Northern China. The sauce is made from sesame paste and sesame oil. |

| Zhajiangmian |  |

炸醬麵 | 炸酱面 | zhájiàngmiàn |

Pastries

| English | Image | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fried butter cake | 奶油炸糕 | 奶油炸糕 | nǎiyóu zhágāo | ||

| Fried cake with fillings | 燙麵炸糕 | 烫面炸糕 | tàngmiàn zhágāo | ||

| Fried sesame egg cake | 開口笑 | 开口笑 | kāikǒuxiào | The name means "open mouth and laugh/smile." | |

| Jiaoquan |  |

焦圈 | 焦圈 | Jiāoquān | Looks like a fried doughnut but is crispier. |

| Sachima | 沙琪瑪 | 沙琪玛 | sàqímǎ | A Chinese pastry from Manchu culture. |

Vegetarian Dishes

| English | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baked sesame seed cake | 燒餅 | 烧饼 | shāobǐng | |

| Bean jelly | 涼粉 | 凉粉 | liángfěn | |

| Beijing yoghurt | 奶酪 | 奶酪 | nǎilào | |

| Cake with bean paste filling | 豆餡燒餅 | 豆馅烧饼 | dòuxiàn shāobǐng | |

| Candied fruit | 蜜餞 | 蜜饯 | mìjiàn | |

| Chatang / Miancha / Youcha | 茶湯 / 麵茶 / 油茶 | 茶汤 / 面茶 / 油茶 | chátāng / miànchá / yóuchá | |

| Chestnut broth | 栗子羹 | 栗子羹 | lìzǐ gēng | |

| Chinese cabbage in mustard | 芥末墩 | 芥末墩 | jièmò dūn | |

| Fermented mung bean juice | 豆汁 | 豆汁 | dòuzhī | |

| Fried cake | 炸糕 | 炸糕 | zhágāo | |

| Fried cake glazed in malt sugar | 蜜三刀 | 蜜三刀 | mìsāndāo | |

| Fried dough twist | 麻花 | 麻花 | máhuā | |

| Fried sugar cake | 糖耳朵 | 糖耳朵 | táng ěrduō | |

| Fuling pancake sandwich | 茯苓夾餅 | 茯苓夹饼 | fúlíng jiábǐng | |

| Glazed / candied Chinese yam | 拔絲山藥 | 拔丝山药 | básī shānyào | |

| Glutinous rice ball | 艾窩窩 | 艾窝窝 | àiwōwō | |

| Glutinous rice cake | 切糕 | 切糕 | qiēgāo | |

| Hawthorn cake | 京糕 | 京糕 | jīnggāo | |

| Jellied beancurd | 豆腐腦 | 豆腐脑 | dòufǔ nǎo | |

| Kidney bean roll | 芸豆卷 | 芸豆卷 | yúndòujuǎn | |

| Millet zongzi | 粽子 | 粽子 | zòngzǐ | |

| Mung bean cake | 綠豆糕 | 绿豆糕 | lǜdòu gāo | |

| Noodle roll | 銀絲卷 | 银丝卷 | yínsījuǎn | |

| Pancake | 烙餅 | 烙饼 | làobǐng | |

| Pease pudding | 豌豆黃 | 豌豆黄 | wāndòu huáng | |

| Preserved fruit | 果脯 | 果脯 | guǒpú | |

| Soybean flour cake | 豆麵糕 | 豆面糕 | dòumiàn gāo | |

| Stir fried hawthorn | 炒紅果 | 炒红果 | chǎohóngguǒ | |

| Stir-fried starch knots | 燒疙瘩 | 炒疙瘩 | chǎo gēdā | |

| Suncake | 太陽糕 | 太阳糕 | tàiyáng gāo | Different from the Taiwanese suncake. |

| Sweetened baked wheaten cake | 糖火燒 | 糖火烧 | táng huǒshāo | |

| Tanghulu | 糖葫蘆 | 糖葫芦 | táng húlú | |

| Tangyuan | 湯圓 | 汤圆 | tāngyuán | |

| Thin millet flour pancake | 煎餅 | 煎饼 | jiānbǐng | |

| Veggie roll | 春餅卷菜 | 春饼卷菜 | chūnbǐng juǎncài | Not to be confused with spring rolls. |

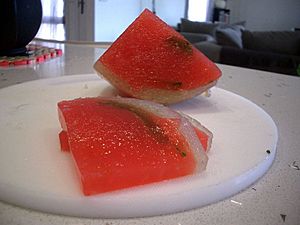

| Watermelon jelly | 西瓜酪 | 西瓜酪 | xīguā lào | |

| Wotou | 窝头 | 窝头 | wōtóu | |

| Xing ren cha | 杏仁茶 | 杏仁茶 | xìngrén chá | |

| Xingren doufu | 杏仁豆腐 | 杏仁豆腐 | xìngrén dòufǔ |

Beijing Delicacies

- Deep-Fried Pie

- Soy Bean Curd

Famous Beijing Restaurants

Many old restaurants in Beijing helped create Beijing cuisine. Sadly, many have closed down. But some have managed to stay open until today. Here are a few of them:

- Bai Kui (白魁): Started in 1780.

- Bao Du Feng (爆肚冯): Started in 1881, also known as Ji Sheng Long (金生隆).

- Bianyifang: Started in 1416, it's the oldest restaurant still open in Beijing!

- Cha Tang Li (茶汤李), started in 1858.

- Dao Xiang Chun (稻香春): Started in 1916.

- Dao Xian Cun (稻香村): Started in 1895.

- De Shun Zhai (大顺斋): Started in the early 1870s.

- Dong Lai Shun (东来顺): Started in 1903.

- Dong Xin Shun (东兴顺): Also known as Bao Du Zhang (爆肚张), started in 1883.

- Du Yi Chu (都一处): Started in 1738.

- Dou Fu Nao Bai (豆腐脑白): Started in 1877, also known as Xi Yu Zhai (西域斋).

- En Yuan Ju (恩元居), started in 1929.

- Fang Sheng Zhai (芳生斋), also known as Nai Lao Wei (奶酪魏), started in 1857.

- Hong Bin Lou (鸿宾楼): Started in 1853 in Tianjin, moved to Beijing in 1955.

- Jin Sheng Long (金生隆): Started in 1846.

- Kao Rou Ji (烤肉季): Started in 1828.

- Kao Rou Wan (烤肉宛): Started in 1686.

- Liu Bi Ju (六必居) Started in 1530.

- Liu Quan Ju (柳泉居): Started in the late 1560s, the second oldest restaurant still open in Beijing.

- Nan Lai Shun (南来顺): Started in 1937.

- Nian Gao Qian (年糕钱): Started in early 1880s.

- Quanjude (全聚德): Started in 1864.

- Rui Bin Lou (瑞宾楼): Originally started in 1876.

- Sha Guoo Ju (砂锅居), started in 1741.

- Tian Fu Hao (天福号): Started in 1738.

- Tian Xing Ju (天兴居):, started in 1862.

- Tian Yuan Jian Yuan (天源酱园): Started in 1869.

- Wang Zhi He (王致和): Started in 1669.

- Wonton Hou (馄饨侯): Started in 1949.

- Xi De Shun (西德顺): Also known as Bao Du Wang (爆肚王), started in 1904.

- Xi Lai Shun (西来顺): Started in 1930.

- Xian Bing Zhou (馅饼周): Started in the 1910s, also known as Tong Ju Guan (同聚馆).

- Xiao Chang Chen (小肠陈): Started in the late 19th century.

- Xin Yuan Zhai (信远斋), started in 1740.

- Yang Tou Man (羊头马): Started in the late 1830s.

- Yi Tiao Long (壹条龙): Started in 1785.

Images for kids

-

Peking duck is a famous duck dish from Beijing

See also

In Spanish: Gastronomía de Pekín para niños

In Spanish: Gastronomía de Pekín para niños