Blacksmith token facts for kids

Blacksmith tokens were a type of unofficial money used in Lower Canada and Upper Canada (now parts of Canada) in the 1820s and 1830s. They were also used in nearby areas like New York and New England in the United States. These tokens were not exactly fake money, but they looked very similar to real coins. They often had different words or no dates, so they weren't exactly copying official money.

These tokens were made to look like old, worn-out British or Irish copper coins. They usually showed a rough picture of King George II or King George III on one side. The other side often had a picture of Britannia (a symbol of Britain) or an Irish harp. Blacksmith tokens were usually lighter than official halfpenny coins. However, people accepted them because there wasn't enough small change available at the time.

Most Blacksmith tokens were made of copper, but a few were made of brass. The pictures on these tokens were often made very poorly on purpose. Because of this, it's rare to find a Blacksmith token in really good condition. Experts who study coins, called numismatists, first talked about these tokens in the late 1800s. An American numismatist named Howland Wood fully described them in 1910. By the late 1830s, Canadian banks started making their own official copper tokens. These new, proper coins eventually replaced the Blacksmith tokens.

We don't know how many of these tokens were made. The people who created them could have gotten into trouble if they were caught. However, many Blacksmith tokens have been found in old collections and during archaeological digs. This shows that some types were quite common. They have been found in places like the Saint John River Valley in Nova Scotia, at Fort York in Toronto, and in Place Royale in Quebec City.

Today, common Blacksmith tokens can cost about C$20-$30. But very rare ones, where only a few or even just one is known, can sell for thousands of dollars.

How They Got Their Name

The name "Blacksmith tokens" comes from an article written in 1885 by R.W. McLachlan. He was writing about Canadian coins and described a specific token. He said:

Before 1837, when there wasn't enough official money, a blacksmith in Montreal made his own coins. When he wanted to have a good time, he would make some of these copper coins to get the money he needed.

Even though this story was about just one coin, the name "blacksmith token" or "blacksmith copper" stuck. Soon, it was used for all coins of this type. Some of the rarest Blacksmith tokens might have been made by one person by hand. But the large number of common tokens suggests that some came from bigger, more professional coin-making places. McLachlan thought they were made in many different places or by one large operation over several years. Newer research suggests they were made in various spots in Lower Canada, Upper Canada, and even the United States.

Studying Blacksmith Tokens

Coin experts like R.W. McLachlan started describing individual Blacksmith tokens in the 1880s. Many were also listed in Pierre-Napoléon Breton's big book about Canadian colonial tokens. Another expert, Eugene Courteau, was the first to notice that some of these coins looked alike. He wrote about this in 1908.

Howland Wood published the first full study of these tokens in 1910. He wrote an article called The Canadian Blacksmith Coppers. Wood noticed that all Blacksmith tokens were made to look like worn-out British half-pence coins. He also found that their designs were often the opposite of the original coins. For example, if a real coin showed King George III facing right, the Blacksmith version would show him facing left. Wood thought this happened because the person carving the coin dies was not very experienced.

Most of these tokens that looked like royal coins were made of copper. A few were made of brass. Wood believed these tokens were made in the early 1800s. He saw one token that was made over a George IV half-penny from 1825. This meant it couldn't have been made before that year. More recent discoveries confirm this, as a Blacksmith token was found made over an Upper Canadian token from 1820.

Besides the tokens that copied English and Irish royal coins, Wood also found a second group. He called these "curiosities and puzzles." These were mules, meaning they mixed parts from different coin dies. One of these mules used a die from a store token made in the United States in 1835. This means the Blacksmith version couldn't have been made before that date. Banks in Canada started making their own official tokens in 1838. So, Wood thought this second group of tokens must have been made between 1835 and 1838. He also noted that these "puzzle" tokens were much rarer than the royal imitation ones.

Wood identified 46 different types of Blacksmith tokens. Later research has found even more. Today, the Charlton catalog lists 56 different types and variations. Blacksmith tokens are now grouped into categories based on what they copied. These include tokens with a royal profile, those with a blank back, and others that copied different types of coins.

Research on these tokens is still ongoing. John Lorenzo has used special X-ray fluorescence studies to learn about their metal makeup. He has found new details and suggests there are at least four main "families" of Blacksmith tokens. These families are linked by the dies used to make them.

'BITIT' Tokens

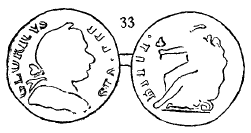

The "BITIT" Blacksmith token (Wood 33) is one of the most common and talked about tokens in this series. One side shows a picture of King George III with what was called a "large pug nose." The other side has a seated Britannia holding a shamrock. Unlike most Blacksmith tokens, this one has words on both sides. However, the tops of the letters are often missing or unclear. This might have been done on purpose.

People have had many different ideas about what the words on this token say. McLachlan thought the front said "GLORIUVS III VIS." Other experts thought "VIS" should be "VTS," which they said was a short Latin word for "Vermont." McLachlan disagreed, believing it was a Canadian imitation of a George III coin. This debate continues today. Some recent studies suggest the "I" should be a "T," supporting the "VTS" idea. But a token at the Bank of Canada Museum, which is struck off-center, doesn't clearly show a "T."

Wood thought the front words read "GLORIOVS III VIS." A newer article claims that some high-quality examples show the first word might be "GEORIUVS." The words on the front have also been read as the strange "BITIT." But one study says the "I" and "T" are actually an "R" and "I," making the word "BRITI," which is short for "BRITISH."

Wood put this token in his "Miscellaneous and Doubtful" group. He thought it might be a royal imitation coin made in England. However, it shares the Blacksmith token feature of the king's head facing the opposite way. McLachlan believed this coin was made in Canada and was common. But it was not in Breton's book about Canadian coins. This might be because Breton thought it was a British import. While some American experts thought it came from Vermont, most other U.S. colonial coin experts did not list it. Even though its origin is still debated, these coins have been found in hoards and archaeological sites in Canada. This proves they were used in Canada.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |