Blas Valera facts for kids

Blas Valera (1544-1597) was a Roman Catholic priest who belonged to the Jesuit Order in Peru. He was also a historian and a linguist. His father was Spanish, and his mother was an indigenous woman. This made him one of the first mestizo (mixed heritage) priests in Peru.

Valera wrote a history of Peru called Historia Occidentalis, but most of it is now lost. However, Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, another famous historian, quoted parts of it in his own history. In 1583, the Jesuits put Valera in jail. They likely did this because he had different ideas, which they called heresy.

Valera believed that the Incas were the rightful rulers of Peru. He also thought that the Inca language, Quechua, was as important as Latin for religious purposes. He even suggested that the Inca religion had prepared the Andean people for Christianity. In 1596, while still under house arrest, he traveled to Spain. He died there in 1597.

According to his biographer Sabine Hyland, Blas Valera cared deeply for the native people of Peru. He bravely tried to protect their culture and create a new way of understanding Christianity in the Andes.

Contents

Blas Valera's Early Life and Studies

Blas Valera was born in Chachapoyas, Peru, around 1544 or 1545. His father, Luis Valera, was a Spanish soldier who helped conquer the Inca Empire. His mother, Francisca Pérez, was an Andean woman, possibly from the Inca royal family.

As a child, Valera spoke Quechua. He later studied Latin and Spanish in the city of Trujillo. He became very skilled with languages. His younger brother, Jerónimo, became a Franciscan religious scholar.

Joining the Jesuit Order

Valera joined the Jesuit Order in Lima in 1568. People described him as humble, stable, and wise. He spent about five years training. He was among the first group of mestizos accepted by the Jesuits to become priests.

The Jesuits were new in Peru. They encouraged using native languages and cultures to spread Christianity. In 1573, Valera became a priest. By 1576, he was teaching Latin and preaching to the Andean people in Cuzco.

He became involved with a group of Inca noblemen. They were part of a religious group called the Name of Jesus confraternity. These nobles worked with the Jesuits to keep their royal rights. They also wanted to show how important Cuzco and the Incas were to the Catholic faith.

In 1577, the Jesuits wanted to move Valera and another priest to Potosí. But the Incas in Cuzco protested. So, his move was delayed until 1578 or 1579. In Potosí, he likely started another Name of Jesus confraternity.

Valera's Imprisonment and Views

In 1582 and 1583, Valera worked in Lima. He helped other priests translate the Roman Catholic catechism (a book of religious teachings) into Quechua and Aymara.

However, he disagreed with some European-born Jesuits. Valera believed that the Inca religion could fit well with Christianity. He also thought that Quechua words could be used to explain Christian ideas.

These different views from Valera and other mestizo priests led to a new rule in 1582. The Jesuits banned mestizos from becoming priests. Soon after this ban, Valera was put in prison by the Jesuits.

He was sentenced to four years in prison and six years of house arrest. He was also permanently stopped from being a priest and from teaching languages. In prison, Valera had to pray and do simple tasks. He also had to undergo weekly "mortifications," which were harsh religious punishments. Valera was offered the chance to join another religious group, but he refused. He said he was innocent.

The main reason for his imprisonment was likely his strong belief that the Incas were the rightful rulers of Peru. He also thought Quechua was better than Spanish and as important as Latin for religion. His imprisonment was kept very secret. His punishment was not decided by a normal trial, like by the Inquisition. Instead, the matter went to the Jesuit leaders in Europe.

On April 11, 1583, Father Andrés Lopez left Peru for Spain. One of his jobs was to personally ask that Valera be removed from the Jesuit Order. The details of Valera's offense were too secret to be written down by the Jesuits. Historian Sabine Hyland thinks the Jesuits wanted to avoid upsetting Philip II of Spain. So, they kept Valera's opinions quiet.

Valera's ideas went against a Spanish policy. This policy was set by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo (who ruled from 1569–1581). Toledo wanted to show that Spanish rule was right. He also wanted to put down the Incas, especially their religion. Before Toledo, the native culture of Peru had mostly survived for 40 years since Francisco Pizzaro defeated the Inca Empire. Toledo started a huge change in native society. Valera's defense of the Incas and their culture went against Toledo's goals. The mestizos, including mestizo priests, who had partly adopted Spanish ways, were seen as a problem. They stood in the way of wiping out native culture, which Toledo and later Viceroys wanted.

Valera asked to go to Rome to explain his case to the Jesuit leader, Claudio Acquaviva. He left Peru in 1594 but spent two years in Quito recovering from an illness. He finally arrived in Spain in May 1596. He was first put in prison there. But on June 3, 1596, Father Cristóbal Mendez wrote to Acquaviva that Valera had changed his views. He was allowed to teach humanities in Cadiz, but not languages or to hear confessions. Later that year, Valera was hurt when an Anglo-Dutch fleet attacked Cadiz. He died on April 2, 1597.

Disputed Claims About Valera

In the 1980s and 1990s, an Italian woman named Clara Miccinelli said she found old documents from the 1600s. These documents claimed that Valera did not die in 1597. Instead, they said he returned to Peru and was the real author of a long book describing Spanish misrule in Peru, not Guaman Poma.

The documents also claimed that the quipus (knotted strings used by the Inca) were a true "written" language, not just a way to record things. They also said that Pizarro used poison to defeat the Incas.

Experts have questioned if these documents are real. Historian Hyland believes the documents are probably from the 1600s. However, she thinks the claims in them are made-up and incorrect. She suggests the documents might show the views of some Jesuits in the 1600s who were critical of Spanish rule.

Blas Valera's Writings

Blas Valera wrote four known works. Most of his writings are lost. But we know about them because other authors used them as sources.

His first known work, written around 1579 or earlier, was a history of how Christianity spread among the native people of the Andes.

His second work was a long history of the Incas. Most of it was destroyed when Cadiz was attacked in 1596. The parts that survived were used and quoted by others, including Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Garcilaso used Valera's work in his book Comentarios Reales de los Incas, published in 1609. Garcilaso said that Valera's Latin writing was "elegant."

Valera also wrote a Quechua Vocabulary. This was more like an encyclopedia. In it, he showed his admiration for the Inca Emperor Atahuallpa. He even said Atahuallpa was a Christian saint in heaven. The "Vocabulario" was used as a source by Giovanni Anello Oliva in his histories of the Incas. Sometimes, Oliva did not say Valera was the source because Valera was not in good standing with the Jesuits.

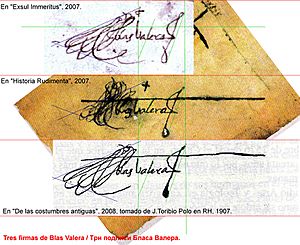

The fourth work is "An Account of the Ancient Customs of Peruvian Natives." This is the only one known to exist completely. Most of this "Account" describes the religion of the Incas in a very positive way. It seems he wrote it to correct negative descriptions of Inca religion by other writers. Valera wrote it while he was recovering from illness in Quito in 1594 and 1595.

See also

In Spanish: Blas Valera para niños

In Spanish: Blas Valera para niños