Burnt Fen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Burnt Fen |

|

|---|---|

The Engine Drain where it meets the River Lark at Lark Engine House |

|

| OS grid reference | TL605875 |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BURY ST. EDMUNDS |

| Postcode district | IP28 |

| EU Parliament | East of England |

Burnt Fen is a flat, low-lying area of land in England. It's located between Littleport in Cambridgeshire and Mildenhall in Suffolk. Rivers surround it on three sides, making it great for farming. However, because it's so low, it needs special pumps to stop it from flooding.

For many years, a group called the Commissioners of the Burnt Fen First Drainage District managed the area's drainage. Later, the Burnt Fen Internal Drainage Board took over. They collect money from landowners to pay for the important work of keeping the area dry.

Contents

Where is Burnt Fen Located?

Burnt Fen is mostly in Cambridgeshire, near the eastern edge of the Isle of Ely. Some parts also stretch into Suffolk and Norfolk. This area is excellent for growing crops. Most of it is actually below sea level. This means it's lower than the normal water levels of the rivers around it.

The rivers surrounding Burnt Fen are:

- The River Great Ouse (also called Ten Mile River) on the northwest side.

- The River Little Ouse (or Brandon Creek) on the northeast side.

- The River Lark on the southwest side.

The A1101 road crosses the area, running from Littleport to Mildenhall. The Ely to Norwich railway line also goes through Burnt Fen. There are four small villages here: Little Ouse, Shippea Hill, Sedge Fen, and Mile End. The Shippea Hill railway station was even called Burnt Fen for a while!

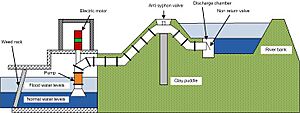

Because the land is so low, it would flood without constant pumping. The Commissioners of the Burnt Fen First District were set up in 1759 by a special law called an Act of Parliament. They managed the drainage ditches and pumping stations. In 1962, the Burnt Fen Drainage District grew a bit. A new group, the Internal Drainage Board, was formed to manage it. They look after about 17,140 acres of land. This includes 42.3 miles of drainage ditches and two pumping stations. One station is on the River Lark, and the other is on the Great Ouse. Water flows into the ditches by itself. Then, the pumps lift it up to 16 feet high to get it into the rivers.

The name "Burnt Fen" likely comes from an old farming method. Since the mid-1600s, people would cut and dry large clumps of rushes. Once dry, they would burn them. The ashes then became fertilizer for the soil. This method, called "paring and burning," was common in the Fens. It helped make the rough land smooth and ready for farming.

Ancient Discoveries in Burnt Fen

Burnt Fen is a very interesting place for archaeologists. They have found many ancient items from the Mesolithic period, which was a long time ago! One of the biggest collections of Bronze Age artifacts ever found in Western Europe was discovered near Isleham. Many of these 6,000 pieces are now on display. You can see them at the Moyses Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds.

The Story of Burnt Fen's Drainage

Burnt Fen is part of the South Level of the Fens. In 1652, a Dutch engineer named Cornelius Vermuyden and his team, called Adventurers, worked to drain this area. They changed the paths of several rivers to improve drainage. This helped turn wet land into farmland. People even held a special celebration at Ely Cathedral to mark this achievement. Burnt Fen was a low area surrounded by the River Great Ouse, the River Little Ouse, and the River Lark.

From the start, there were disagreements. Some people wanted to use the rivers for boats, while others wanted them for drainage. A big problem for Burnt Fen was that the land kept sinking. This happened as water was removed from the peat soil. Also, the light, dry soil would blow away in the wind. Soon, water could no longer flow from the land into the rivers by itself. The main river authority, the Bedford Level Corporation, didn't control the smaller rivers. Landowners tried to build windmills to pump water. But there was no overall plan. This led to arguments and even lawsuits between neighbours.

The First Drainage Managers

Because of these problems, a special law was passed in 1759. This law created two drainage districts. Each district had its own group of managers, called Commissioners. The first group was for Burnt Fen, and the second was for Lakenheath Little Fen. Important people like the Lord Bishop of Ely were Commissioners. Also, anyone who owned 300 acres of "taxable land" became a Commissioner. People who owned over 6 acres could vote for elected Commissioners each year. "Taxable land" meant any land that could be flooded and would benefit from drainage.

The Commissioners first met on June 6, 1760. They planned to take over all the existing drainage windmills. They also planned to build new ones and dig main drainage channels. These channels would carry surface water to the mills and then into the rivers. To pay for this, they could borrow money. They also charged a drainage fee of 1 shilling (about 5p) per acre. This fee would go up to 1/6d (about 7.5p) after seven years. However, they greatly underestimated the costs. They soon faced money problems. Despite heavy flooding in 1761/2, which meant no fees were collected, they owned eight mills by 1774. Each mill used a scoop wheel to lift water into the rivers. Keeping the mills working was expensive, especially with the cost of wood rising due to shipbuilding.

To protect the area, they built a large bank across its southeastern edge. This bank stopped floodwater from Lakenheath Little Fen from reaching Burnt Fen. Building and maintaining these banks was very costly. So, in 1772, a second law was passed. This allowed them to raise the drainage fee to 2 shillings (10p) per acre for ten years. It also added penalties for late payments. A third law in 1796 raised the fees again to 3/6 (17.5p) per acre. By 1807, they had borrowed £11,500 and struggled to pay it back. A fourth law increased the fees once more and changed how the Commissioners were chosen.

Progress was not always easy. In 1777, the river banks broke badly, ruining many landowners. However, a machine called the bear was used to clean the river bottoms. By 1782, land prices had gone up. An estate bought for £200 could be sold for £2,000 after better banks and mills were built.

Machines Take Over

Windmills only worked when the wind blew, which wasn't always when they were needed most. So, the Commissioners looked into using machines. In 1829, they asked an engineer, Mr. W. C. Mylne, for advice. He suggested using steam engines. So, they ordered a 40 horsepower (hp) engine from Boulton Watt and Co. This engine would power two scoop wheels. The engine cost £1,184, and its building cost £836. It was set up where the Whitehouse Drain met the River Little Ouse (Brandon Creek). It started working in 1832 and was called the Brandon Engine. There were some early problems, but once fixed, the new system proved very good at draining the Fens.

The Brandon Engine served the northern part of the Fen. The Commissioners decided a similar engine was needed for the south. Boulton Watt and Co. again supplied a 40 hp engine, this time with three boilers. This new engine was placed on the River Lark. To get water to it, they had to build the Engine Drain. The engine started working in 1842 and had no major problems. By 1848, the Brandon Engine was getting old. A new type of boiler was installed. They also tried to improve the scoop wheels as the land kept sinking. Larger scoop wheels were added to the Brandon Engine in 1860 and to the Lark Engine soon after.

The financial situation of the Drainage District had improved since 1807. They were paying back their old debts. A fifth Burnt Fen Act was passed in 1823. This law recognized that horses and carts using the river banks caused damage. It allowed charges for such use. The Bedford Level Corporation also helped with bank repair costs.

In 1879, the two drainage districts were reorganized. The First District became the Burnt Fen District. The Second District became the Mildenhall District.

The Age of Steam Power

By 1882, scoop wheels couldn't be improved much more. The Commissioners asked engineer George Carmichael for advice on using centrifugal pumps. Carmichael suggested a new engine and pump. An 80 hp engine from Hathorn Davey and Co. was bought. It would power a large, horizontally placed centrifugal pump. The Lark Engine's new setup was delayed by problems with its power and by floods. But by November 1883, the issues were fixed. The new engine worked so well that the Commissioners could wait to decide about the Brandon Engine.

When they finally looked at the Brandon Engine in 1890, it was in bad shape. By then, the drains in the northern and southern parts of Burnt Fen were connected. This meant either engine could pump the whole area in an emergency. Plans for a new Brandon Engine were made right away. Hathorn, Davey and Co. supplied a pump that could move 75 tons of water per minute. It was ready by October 1892.

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, the Commissioners hired teams of "gaulters." These men got their name from "gault," a type of clay from Roswell Pits at Ely. They used this clay to repair the river banks. The teams had three men and five boats, each carrying 8 tons of gault. The Commissioners owned the boats, but the men provided their own horse, shovels, and wheelbarrows. In 1886, new pay terms were agreed upon. In 1920, the Ouse Drainage Board was created. They took over maintaining the river banks. So, the Commissioners let go of the gaulters and sold the boats.

Making Things Modern

As the land continued to sink, the Commissioners looked for ways to improve the engines in 1919. They thought about replacing the steam engines with oil engines. In 1924, they asked Blackstone and Company Limited to supply two 250 hp oil engines. Each engine would have a 42-inch Gwynne rotary pump, able to pump 150 tons per minute. These new engines were built next to the old ones, which could still be used as backup. The new Brandon engine was installed by autumn 1925. The completion of the Lark engine was a big celebration, with all taxpayers invited to the opening party.

In 1926, more improvements came. Instead of using spades to maintain the drains, they got a petrol/paraffin dragline excavator from Priestman Bros. Limited. The Brandon steam engine didn't last long as a backup. It was taken out of service in April 1927 and sold for scrap in 1933. The Lark engine lasted longer. It was kept working until 1945, though it wasn't used much. In 1939, they considered upgrading the engines again. But World War II delayed this. Finally, in 1941, they got approval to install a Crossley 300 bhp engine with a 42-inch Gwynne rotary pump. This pump could move 150 tons per minute. Work finished in January 1945. The Lark steam engine was sold for scrap in July, and its building became a workshop.

The Brandon pumping station was finally closed in the 1950s. The White House drain, which fed it, had become deeper as the land sank. The soil around it was unstable and needed constant repairs. The pumping station was actually on a "hill" rather than the lowest part of the Fen. So, they decided to build a new station at Whitehall on the River Great Ouse. This needed a new 1.25-mile main pumping drain to connect it to the old drains. Two 210 bhp electric motors with vertical pumps were supplied by W. H. Allen Sons and Company Ltd. The new station opened on September 10, 1958.

Growing the Drainage Area

In 1959, the Commissioners looked into draining other areas near Burnt Fen. Landowners in Sedge Fen had asked for help. A report suggested that the best idea was to add these areas to an Internal Drainage Board. So, the Commissioners asked to expand their District by 2,059 acres. This included parts of Sedge Fen, Decoy Fen, and Redmere. The expansion was approved in 1962. This new order cancelled all the old Burnt Fen Acts. After 203 years, the Commissioners were replaced by an elected board of 20 members. This new group was called the Burnt Fen Internal Drainage Board.

The Lark Engine pumping station was upgraded again in 1974. The old Blackstone engine was kept as a historical piece. The Crossley engine became the backup. The Crossley engine house was made bigger to fit a 230 bhp Dorman Diesel engine. This engine powers a 33-inch Allen Gwynne vertical pump. A wooden plaque was put up, showing all the engines installed since 1842. Mrs F. G. Starling officially opened the upgraded station on May 25, 1976. More improvements followed. British Rail agreed to remove the skew bridge that carried the railway line over the main drain. It was replaced by a culvert. This allowed the main pumping drain to the Lark Engine to be made deeper and wider. This helped water flow better between the two halves of Burnt Fen.

Even with all these changes, the Lark Engine house still has a poem written in 1842 by William Harrison. He was the Superintendent of the Works from 1831 to 1871.

- In fitness for the urgent hour,

- Unlimited, untiring power,

- Precision, promptitude, command,

- The infant's will, the giant's hand,

- Steam, mighty steam, ascends the throne,

- And reigns lord paramount alone.

How Burnt Fen is Managed Today

The Burnt Fen IDB manages about 17,140 acres of land. They maintain 39 miles of drains to move extra water to their two pumping stations. Since 2002, they have been part of the Ely Group of Internal Drainage Boards. This is a larger group of ten IDBs in the area. Being part of this group helps them save money and work more efficiently by sharing resources. They share offices at Prickwillow, but the Burnt Fen IDB is still its own independent group.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |