Cantonal rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cantonal rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

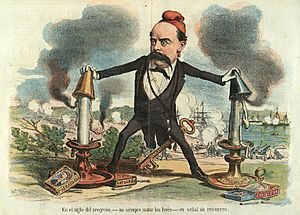

The Cantonal Rebellion was a major uprising that happened in Spain between July 1873 and January 1874. It took place during the First Spanish Republic. This rebellion was started by a group called the "intransigent" federal Republicans. They wanted to create a Federal Republic right away, starting from local areas (called "cantons") and building up. This was different from what the government wanted. The president, Francisco Pi y Margall, believed the new Federal Constitution should be written and approved first by the national parliament, called the Cortes.

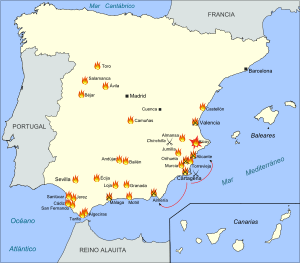

The rebellion began on July 12, 1873, in Cartagena. Before this, a smaller event known as the Petroleum Revolution had already started in Alcoy. The Cantonal Rebellion quickly spread to regions like Valencia, Murcia, and Andalusia. In these areas, people formed their own local governments, or "cantons." They hoped these cantons would then join together to form the Spanish Federal Republic.

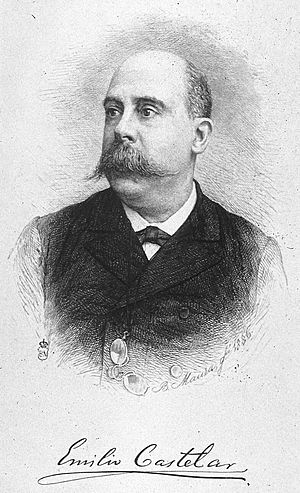

The government of Pi y Margall tried to end the rebellion through a mix of talking and force. When this didn't work, the next president, Nicolás Salmerón, used the army to stop the uprising. Generals Arsenio Martínez Campos and Manuel Pavia led the troops. The government after Salmerón's, led by Emilio Castelar, continued this strong approach. Castelar's government began a siege of Cartagena, which was the last place holding out. Cartagena finally fell on January 12, 1874. This happened just a week after General Pavia's coup, which ended the First Spanish Republic and led to a temporary dictatorship.

Even though the government at the time saw the Cantonal Rebellion as a movement to break Spain apart, historians today believe it was actually about changing how the country was organized. The rebels wanted to reform the state structure, not split Spain into separate countries.

Contents

Spain Becomes a Republic

Proclaiming the Republic

On February 11, 1873, King Amadeo I stepped down from his throne. The very next day, the National Assembly (Spain's parliament) declared Spain a Republic. This decision was made with many votes in favor. However, they didn't decide if it would be a "unitary" republic (with a strong central government) or a "federal" republic (with more power given to local regions). They left that decision for a future parliament, called the Constituent Cortes.

The National Assembly quickly appointed Estanislao Figueras as the first president of the Republic. His government faced a big challenge: restoring order. Many federal Republicans, who saw the Republic's creation as a new revolution, had taken power by force in various places. They formed "revolutionary juntas" (councils) that didn't recognize Figueras's government. They thought the government in Madrid was too slow. In many villages, people believed the Republic meant they would get land. Farmers demanded that local governments immediately divide up large farms. People also wanted to get rid of the unpopular quintas, which was compulsory military service for young men.

Francisco Pi y Margall, who was the Minister of the Interior, was in charge of bringing back order. He was a strong supporter of "pactist" federalism, which meant building the federal system from the local level up. Even though the juntas were doing what he believed in, Pi y Margall worked to dissolve them and replace the local governments that had been taken over. He wanted to respect the law, even if it went against some of his supporters' wishes.

Pi y Margall also had to deal with attempts by the Provincial Deputation of Barcelona to declare a "Catalan State." This happened twice. The first time, he managed to convince them to stop through telegrams. The second time, on March 8, was more serious. Radicals in Madrid tried to stop the Republic from becoming federal. Pi y Margall's telegrams weren't enough, so President Figueras himself had to go to Barcelona to ask them to withdraw their declaration.

Another attempt by the Radical Party to stop the Constituent Cortes from meeting happened on April 23. "Intransigent" Republicans wanted the Federal Republic to be declared immediately, without waiting for the Cortes. But the government stuck to the law. Pi y Margall received many messages asking him to simply confirm the will of the local areas, saying the Federation should be built "from the bottom-up."

The Federal Republic is Declared

Elections for the Constituent Cortes were held in May. The Federal Democratic Republican Party won a huge victory because other parties didn't participate. However, the federal Republican deputies in the Cortes were divided into three main groups:

- The "intransigents" were about 60 deputies. They wanted the Federal Republic to be built from the ground up, starting with local towns, then regions (cantons), and finally the national level. They also wanted social changes to help working people.

- The "centrists" were led by Pi y Margall. They also wanted a federal republic but believed it should be built from the top down. This meant writing a federal Constitution first, and then forming the cantons.

- The "moderates" were the largest group, led by Emilio Castelar and Nicolás Salmerón. They wanted a democratic Republic that included all liberal ideas. They thought the Cortes should focus on approving a new Constitution.

Despite these differences, they all agreed to proclaim the Federal Democratic Republic on June 8. This happened a week after the Constituent Cortes opened.

Challenges for the Federal Governments

Soon after, President Estanislao Figueras resigned. He suggested Pi y Margall take his place, but the "intransigents" disagreed. Figueras then learned that "intransigent" generals, like Juan Contreras and Blas Pierrad, were planning a coup to start the federal Republic "from below." Fearing for his life, Figueras fled to France on June 10.

The coup attempt happened the next day. Federal Republicans surrounded the Congress of Deputies building in Madrid, and General Contreras took over the Ministry of War. To solve the crisis, "moderates" like Castelar and Salmerón suggested Pi y Margall become president. They thought he could control the "intransigents" because he was close to their ideas. The "intransigents" agreed, but only if the Cortes elected the government members.

Pi y Margall's government program focused on ending the Third Carlist War, separating the Church and the State, ending slavery, and making reforms for working women and children. He also wanted to return communal land to the people, but this law wasn't approved.

However, the "intransigents" immediately opposed Pi y Margall's government. They felt his program didn't include important federalist policies, like getting rid of certain taxes. The "intransigent" ministers also made it hard for the government to work. This led to a proposal to give the president the power to choose and remove ministers freely. This would allow Pi y Margall to replace the "intransigent" ministers with "moderates." The "intransigents" responded by demanding the Cortes become a "Convention" with a "Public Health Board" holding executive power. This was rejected. On June 27, the "intransigents" tried to remove the government, but the crisis ended with "moderates" joining the government, strengthening Pi y Margall's position. The new government's goal was "order and progress."

On June 30, Pi y Margall asked the Cortes for special powers to end the Carlist war, but only in the Basque Country and Catalonia. The "intransigents" strongly opposed this, seeing it as a move towards "tyranny." Even though the government promised it would only apply to Carlists, the "intransigents" were worried. Once approved, the government announced that young men would be called up for military service.

The Cantonal Rebellion Begins

"Intransigents" Leave Parliament

The "intransigents" reacted to Pi y Margall's "order and progress" policy by leaving the Cortes on July 1. They were upset because the civil governor of Madrid had limited individual rights. In a public statement on July 2, they said they were determined to bring about the changes the Republican Party had always supported. They felt the government was destroying their goals.

Only one deputy, Navarrete, stayed in the Cortes. He explained that the "intransigents" felt Pi y Margall's government lacked energy and had given in to the enemies of the Federal Republic. Pi y Margall replied that the "intransigents" wanted a revolutionary government, which would have meant a dictatorship and the end of the Constituent Cortes. He argued that the Cortes were bringing the Federal Republic without major problems.

After leaving the Cortes, the "intransigents" pushed for the immediate formation of "cantons," which started the Cantonal Rebellion. They formed a Public Health Committee in Madrid to lead it. However, local federal Republicans mostly took charge in their own cities. Within two weeks of the "intransigents" leaving the Cortes, the revolt had spread to Murcia, Valencia, and Andalusia.

Even though there was no single leader for the rebellion, and each canton made its own announcements, the rebels generally wanted the same things. They aimed to replace all existing authorities, get rid of unpopular taxes (like those on tobacco and salt), take over church property, and make social changes to help poor workers. They also wanted to pardon political prisoners, replace the regular army with local militias, and set up public health boards as governing bodies.

On July 18, after the rebellion started in Cartagena and other cities, the Madrid Public Health Committee ordered that Public Health Committees be formed everywhere the federal party was strong. These committees would represent the people's power. They also said that local areas (municipalities, provinces, and cantons) should declare their own independence in terms of administration and economy. These committees would not dissolve until 15 days after a federal agreement was made, to ensure the people weren't tricked.

On August 22, when only the cantons of Málaga and Cartagena were still active, a deputy named Casualdero explained in the Cortes that the uprising wasn't illegal. He said it was simply the true federal idea being put into practice, from the bottom up. He argued that the canton gives power to the federation, not the other way around.

Cartagena Canton Declared

After the "intransigents" left the Cortes, the Public Health Committee in Madrid decided to move to Cartagena. Cartagena was chosen because its port was well-protected by forts and artillery, making it very strong against attacks from both sea and land. The Public Health Committee formed a War Commission, led by General Juan Contreras, who planned to start revolts in Cartagena, Valencia, Barcelona, Seville, and Murcia.

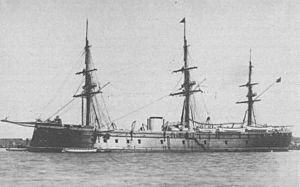

The uprising in Cartagena began at 5 AM on July 12. A "Revolutionary Public Salvation Junta" had been set up an hour earlier. The signal for the revolt was a cannon shot from Galeras Castle. This shot warned that the African regiment, which was supposed to replace the volunteer garrison, had left. Some say the cannon shot was a signal to the frigate Almansa that the defenses were taken.

The fort's commander, a postman named Sáez, wanted to fly a red flag but didn't have one. He mistakenly hoisted a Turkish flag, thinking the crescent moon wouldn't be noticed. But a Navy commander saw it and reported it. To fix this, a volunteer cut himself with a razor and stained the crescent with his blood, turning the Turkish flag into a red cantonal flag.

At the same time, a group of volunteers took over the town hall, setting up the "Revolutionary Public Salvation Junta." Other groups occupied the city wall gates. The civil governor of Murcia, Antonio Altadill, arrived the next day with the Murcian federal deputy Antonio Gálvez Arce, known as Antonete. Seeing that the rebels controlled the city, the governor advised the City Council to resign, which they did. Soon after, the Junta raised the red flag over City Hall and declared the Murcian Canton. They appointed Antonete Gálvez as the general commander of their forces. In their public statement, the Junta said they were proclaiming the Murcian Canton to defend the Federal Republic. Antonete Gálvez and General Juan Contreras then took control of the naval base's warships without any fighting.

The civil governor told President Pi y Margall that neither the "Volunteers of the Republic" nor the Civil Guard were obeying his orders. When he tried to go to Madrid, rebels stopped him at a train station. So, on July 15, the "Revolutionary Junta" of Murcia was formed, led by deputy Jerónimo Poveda. They raised the red flag at City Hall and the archbishop's palace, which became their headquarters. In their public statement, the Junta announced their first actions, such as pardoning political prisoners, taking church property, and redistributing land. They explained that they formed because the government was slow to establish the federation and had appointed disloyal military leaders.

The manifesto stated that local "Revolutionary Juntas" would organize municipal administration under the federal system. It also announced commissions to arm and defend the Murcian Canton and to connect with neighboring provinces. Both would be "under the orders of General Contreras and citizen Antonio Gálvez," showing that the Murcia Junta was under Cartagena's leadership for the Murcian Canton.

On July 15, General Juan Contreras also released a statement. He announced that he had taken up arms for "Federal cantons!" and highlighted the support he had, especially from the Navy. He asked government forces not to fight against the people or their "brothers in arms." He promised not to stop fighting until the people had their desired federation.

Salmerón's Government and Repression

Nicolás Salmerón became the next President of the Executive Power. He was a "moderate" federalist who believed in working with conservative groups and slowly moving towards a federal republic. As soon as he took office, he replaced the Republican General Ripoll with General Manuel Pavia, who was less loyal to the Federal Republic, to lead the army in Andalusia. Salmerón told Pavia that if he could get a soldier to fire against a cantonalist, order would be saved.

Forming the Provisional Government of the Spanish Federation

Salmerón becoming president made the cantonal rebellion even stronger. The "intransigents" believed that with him, it would be impossible to achieve a Federal Republic, even "from above." They decided that through the cantonal uprising, they would finally bring down the central government and establish the federal system "from below." On July 20, Salmerón's government declared cantonal warships to be pirates. In response, on July 22, the cantonalists declared the Madrid government to be traitors.

On July 24, the cantonalists, along with "intransigent" deputies and the Junta of Cartagena, created the "Provisional Directory." This was meant to be the main authority to unite and expand the cantonal movement. The Directory initially had three members: Juan Contreras, Antonio Gálvez, and Eduardo Romero Germes. Two days later, it expanded to nine members. Finally, on July 27, the Provisional Junta became the "Provisional Government of the Spanish Federation."

Rebellion Spreads and Intensifies

After Salmerón's government formed, the cantonal movement grew. By July 23, the uprising had spread to Andalusia and Levante, and even to parts of Salamanca and Ávila. With the ongoing Carlist conflict, this meant 32 provinces in Spain were in rebellion.

On July 17, during a large event in Valencia, the crowd shouted "Long live the Valencian Canton!" The next day, the militia took over key parts of the city, and by 11 PM, the Valencian Canton was declared. On July 19, the "Revolutionary Junta" of the Canton was elected, led by Pedro Barrientos. The civil governor fled. By July 22, 178 towns in the province of Valencia had joined the Canton. The Junta officially declared the Valencian Canton in Valencia's main square, which was renamed "the Plaza of the Federal Republic." They paraded 28 unarmed militia battalions and played the La Marseillaise anthem. The Junta promised to maintain order, saying they weren't trying to cause a social revolution or threaten economic interests, but to establish rights, freedom, and order.

A day earlier, on July 21, deputy Francisco González Chermá left Valencia with volunteers and police to declare the Canton of Castellón. He dissolved the Provincial Council and declared the Canton. However, unlike Valencia, many towns in the province of Castellón were against cantonalism, as many were Carlists. This allowed conservative forces to quickly dissolve the canton. González Chermá escaped back to Valencia. The Canton of Castellón lasted only five days.

On July 19, the Canton of Cádiz was declared. The US consul in the city called it "a real revolution." The Public Health Committee, led by Fermin Salvochea, said it was formed to save the federal Republic and support the movement in Cartagena and Seville. Both the civil and military governors joined the uprising, and the cantonal red flag flew over all official buildings. They received war supplies from the Canton of Seville.

On July 21, the Canton of Málaga was declared. Málaga had already been mostly independent from the central government since the Federal Republic was proclaimed. On July 25, during a meeting to elect the Public Health Committee, many "intransigent" Republicans were arrested. The next day, 45 of them were sent to Melilla.

Other uprisings happened in Andalusia, with cantons declared in Seville (July 19) and Granada (July 20), as well as in smaller towns like Loja, Bailén, Andújar, Tarifa, and Algeciras. In the Murcia Region, cantons were declared in Almansa and Jumilla.

The cantonal rebellion also occurred in some places in the provinces of Salamanca and Toledo. In Extremadura, there were attempts to form cantons in Coria, Hervás, and Plasencia. A newspaper, El Cantón Extremeño, encouraged the creation of a canton linked to Lusitania and urged readers to take up arms if needed.

Common goals in the cantonal declarations included getting rid of unpopular taxes, taking church property, helping workers, pardoning state prisoners, replacing the army with militias, and forming public health committees.

Cartagena's Expeditions

The Canton of Cartagena launched expeditions by sea and land for two main reasons. First, they wanted to spread the rebellion to distract enemy forces and break any encirclement. Second, they needed supplies and money for their 9,000 troops, as Cartagena's own resources were not enough.

The first sea expedition happened on July 20. General Contreras went to Mazarrón and Águilas on the Murcian coast with the paddle steamer Fernando el Católico. At the same time, "Antonete" Gálvez went to Alicante with the ironclad warship Vitoria. Both missions were initially successful. Mazarrón and Águilas joined the Murcian Canton, and Gálvez declared the Canton of Alicante. However, Alicante was retaken by government forces three days later.

When the Vigilante, which Gálvez had taken in Alicante, was returning to Cartagena on July 23, it was stopped by the German armored frigate SMS Friedrich Carl . This was because Salmerón's government had declared all ships flying the red cantonal flag to be "pirates," meaning any country's ships could capture them. The German commander also demanded the frigate Vitoria. Cartagena handed over the Vigilante but kept the Vitoria safe in port.

Meanwhile, in Murcia, the first major land expedition was organized for Lorca, a city that didn't want to join the Canton of Cartagena. "Antonete" Gálvez led 2,000 men and four cannons. They arrived on July 25, raised the flag, and set up a Public Salvation Board. But the Murcian canton in Lorca lasted only one day. As soon as Gálvez's forces returned to Murcia on the 26th, the local authorities came back and dismissed the Junta.

The second sea expedition aimed to spread the revolt along the Andalusian coast from Almería to Málaga. On July 28, General Contreras left Cartagena with the steam frigate Almansa and the Vitoria, carrying two regiments and a Marine infantry battalion. The next day, they arrived at Almería. Contreras demanded money and that military forces leave the city so people could decide whether to proclaim a Canton. Almería refused and prepared its defenses. On the morning of the 30th, the cantonal ships bombed the city, but Almería did not surrender. Contreras then sailed to Motril in Granada, where he received financial aid.

On August 1, near Málaga, the Almansa was stopped by British and German warships. They forced it and the Vitoria to return to Cartagena, saying the cantonal frigates were about to bomb Málaga. The crews were forced off the ships, and General Contreras was briefly detained. The Almansa and Vitoria were taken to Gibraltar and later returned to the Spanish government.

The second land expedition from Cartagena, on July 30, was aimed at Orihuela, a city with many Carlists. "Antonete" Gálvez led forces from Cartagena and Murcia. They entered the city at dawn, fighting local guards and police. After their victory, they returned to Cartagena the next day with prisoners.

In early August, "Antonete" Gálvez and General Contreras led a third land expedition of 3,000 men towards Chinchilla. They wanted to cut off General Arsenio Martínez Campos's railway connection to Madrid. They initially pushed back Martínez Campos's troops. But when they heard that the Canton of Valencia had fallen, they retreated. Government forces counterattacked, causing panic among the Murcian canton troops. Gálvez and Contreras managed to reorganize their forces and returned to Murcia on August 10. The Battle of Chinchilla was a disaster for the Murcian canton, as they lost about 500 men and much equipment. More importantly, it left Martínez Campos free to occupy Murcia.

Crushing the Cantonal Movement

The Salmerón government's goal was to restore the "rule of law." This meant defeating both the Carlists and the Cantonalists to save the Republic. To stop the cantonal rebellion, Salmerón took strong actions. He fired civil governors, mayors, and military leaders who had supported the cantonalists. He then appointed generals like Manuel Pavia and Arsenio Martínez Campos to lead military expeditions to Andalusia and Valencia.

Salmerón also called up army reservists, strengthened the Civil Guard with 30,000 men, and appointed government representatives in the provinces with the same powers as the Executive. He allowed provinces to collect war taxes and organize local armed groups. He also declared that ships held by the Canton of Cartagena were pirates, meaning any ship could capture them. Thanks to these measures, the different cantons surrendered one by one, except for Cartagena, which held out until January 12, 1874.

General Manuel Pavia left Madrid for Andalusia on July 21. He arrived in Córdoba two days later. Before his arrival, General Ripoll had already stopped an attempt to declare the canton of Córdoba. Pavia quickly restored discipline among his troops and then prepared to attack the Canton of Seville, believing its fall would weaken the other Andalusian cantons. Pavia's troops left Córdoba for Seville on July 26. After two days of heavy fighting, they occupied Seville's City Hall on July 30. Control of the city was complete the next day, with 300 government casualties. On August 1, Pavia officially entered Seville, and his troops disarmed the forces of the Canton of Seville in the province's towns.

Cartagena: The Last Stand

Siege by Castelar's Government

On September 7, 1873, Emilio Castelar became President of the Executive Power. By this time, the cantonal rebellion was almost over, with only Cartagena remaining as a stronghold.

Castelar was deeply concerned by the chaos the cantonal rebellion had caused. He later described how Spain seemed to be falling apart during that summer. He felt that the idea of legality had been lost, with ministers defying parliament and people revolting against the law. He worried that the country was dividing into many small parts, like what happened after the fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba. He mentioned strange ideas from provinces, like reviving the ancient Crown of Aragon or an independent Galicia under England's protection. He noted that the uprising happened against a very federal government, just as a federal Constitution was being drafted.

Just two days after becoming president, Castelar got special powers from the Cortes. These powers were similar to those Pi y Margall had requested to fight the Carlists, but now they extended to all of Spain to end both the Carlist war and the cantonal rebellion. His next step was to propose suspending the Cortes sessions, which would stop the debate on the federal Constitution. On September 18, this proposal was approved. The Cortes were suspended from September 20, 1873, until January 2, 1874.

The special powers and the suspension of the Cortes allowed Castelar to govern by decree. He immediately used this to reorganize the army, call up reservists, raise an army of 200,000 men, and ask for a loan of 100 million pesetas to pay for the war.

On September 18, the same day the Cortes voted to suspend sessions, the newspaper El Cantón Murciano in Cartagena published a message from "Antonete" Gálvez to the cantonal troops. He told them that anyone who said Cartagena would surrender was a traitor, and that the city would never be given up. The morale of Cartagena's 75,000 inhabitants was still high, as shown by a popular song:

Castillo de las Galeras,

Be careful when you shoot

Because my lover will pass

With the flag of blood

Around this time, the cantonal five-peseta coins began to circulate. A decree from the Junta said that Cartagena wanted to be the first to spread a lasting memory of justice and brotherhood to future generations.

By late October and early November 1873, people in Cartagena started to show signs of weariness from the long siege. On November 2, a demonstration demanded elections, which the Sovereign Salvation Junta agreed to, but the results didn't change the Junta's makeup. Meanwhile, General Ceballos, leading the government forces, sent spies into the city. They tried to bribe the canton leaders, who refused, though some officers were arrested for accepting money.

The spirits of the besieged people dropped even more when the bombing of the city began in late November. On November 14, the Minister of War suggested throwing 5,000 shells into the city to break the defenders' morale. The bombing started on November 26, 1873, without warning, and continued until the last day of the siege. A total of 27,189 shells were fired, causing 800 injuries, 12 deaths, and damage to most buildings. Only 28 houses were left untouched. After the first week, General Ceballos resigned, saying he lacked resources to take the city before the Cortes reopened on January 2. On December 10, General José López Domínguez replaced him.

Cartagena Surrenders After Pavia's Coup

Castelar's efforts to work with constitutionalists and radicals were opposed by "moderate" Nicolás Salmerón and his supporters. They believed the Republic should only be built by "true" republicans. Salmerón's group showed their opposition in December 1873 by voting against Castelar's proposal for elections to fill vacant seats.

After Castelar's parliamentary defeat, Cristino Martos, a radical leader, and General Serrano, a constitutionalist leader, planned a coup. They wanted to prevent Castelar from being replaced by a no-confidence vote that Pi y Margall and Salmerón were expected to present when the Cortes reopened on January 2, 1874.

When the Cortes reopened on January 2, 1874, the captain general of Madrid, Manuel Pavía, had his troops ready for the coup. On the other side, "Volunteers of the Republic" were ready to act if Castelar won. The Cartagena cantonalists had even been told to resist until January 3, hoping an "intransigent" government would form and "legalize" their situation. When the session began, Nicolás Salmerón announced he was no longer supporting Castelar. Emilio Castelar responded by calling for a "possible Republic" that included all liberals, even conservatives.

The Castelar government was defeated by a vote of 100 in favor and 120 against. A deputy immediately informed General Pavía, who ordered his regiments to march to the Congress of Deputies. It was almost 7 AM.

When Salmerón received a note from General Pavia telling him to "vacate the premises," he stopped the vote and told the deputies about the serious situation. Soon after, the Civil Guard forced their way into the Congress building, firing shots into the air, causing most deputies to leave.

Castelar refused General Pavia's offer to lead the government, as he didn't want to stay in power through undemocratic means. So, the presidency of the Republic was taken over by Francisco Serrano, leader of the Constitutional Party. His main goals were to end the cantonal rebellion and the Third Carlist War. In a public statement on January 8, 1874, Serrano justified Pavia's coup. He said the government that would have replaced Castelar's would have led to Spain breaking apart or the Carlists winning. He then announced that a new parliament would be called to decide the future form of government (Republic or Monarchy).

Serrano's new government (which was like a dictatorship, as the Cortes were dissolved and the 1869 Constitution was suspended) faced resistance in Barcelona. On January 7 and 8, barricades were built, and a general strike was declared. There were clashes with the army. On January 10, Serrano's government dissolved the Spanish section of the International Workingmen's Association (AIT) for "violating property, family, and other social bases." The Civil Guard occupied their offices, and internationalist newspapers were shut down.

When news of Pavia's coup reached Cartagena, the besieged people lost hope. They felt it was a surrender. However, they continued a desperate and heroic defense, as recognized by General José López Domínguez, who commanded the government army besieging the city. On January 6, at 11 AM, the artillery park's powder storage exploded, killing 400 people who had taken shelter there. It's unclear if it was caused by a shell or sabotage. This was the final blow to Cartagena's ability to resist. Neither "Antonete" Gálvez nor General Contreras could lift the spirits of the people.

On the afternoon of January 11, a large meeting was held. It was decided to surrender. The Revolutionary Junta asked Antonio Bonmatí i Caparrós of the Spanish Red Cross to negotiate with the government army. This happened even though other leaders, including "Antonete" Gálvez and General Contreras, wanted to keep resisting. Soon after, a commission from the assembly surrendered to General López Domínguez. At 9 AM the next day, January 12, the commission read López Domínguez's surrender conditions to the assembly. These included a pardon for the crime of rebellion, except for Junta members.

While the commission was negotiating, most Junta members, led by "Antonete" Gálvez and General Contreras, along with hundreds of other cantonalists, boarded the frigate Numancia. They left Cartagena's port at 5 PM on January 12, escaping the government fleet due to the ship's speed. They arrived in Oran (Algeria) the next day.

Meanwhile, the commission returned to Cartagena with López Domínguez's surrender conditions, which hadn't changed much. The general said he would no longer negotiate and gave them until 8 AM on January 13 to accept. Once accepted, General López Domínguez entered Cartagena with his troops that day. He was promoted to lieutenant general and received the Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand.

Aftermath

The surrender terms for Cartagena were considered fair for the time. Those who surrendered, including officers and soldiers from both land and sea forces, volunteers, and militias, were pardoned. However, members of the Revolutionary Junta were not pardoned.

The Minister of the Interior, Eugenio García Ruiz, who was a unitary republican, acted very harshly against the federalists. He even tried to exile Francesc Pi y Margall, who had not been involved in the cantonal rebellion, but the rest of the Serrano government opposed this. García Ruiz was known for his strong anti-federalist views and had attacked Pi y Margall for years.

García Ruiz imprisoned and deported hundreds of people, simply for being "cantonalists," "internationalists," or "agitators." Many were sent to the Spanish colony of the Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean, 3,000 kilometers from the Philippine Islands (which also received deportees). These places were very isolated, and families often had no news of them. The official number of deportees to the Marianas and the Philippines was 1,099. There are no records for those sent to Cuba or held in Spanish prisons. Life in the Marianas was very difficult due to the hot, humid climate. Only eight prisoners are known to have escaped.

Most of the cantonal movement leaders, including "Antonete" Gálvez and General Contreras, escaped to Oran. They were held by French authorities until February 9. The frigate "Numancia" was returned to the Spanish government on January 17, but the people on board were not. Later, during the Bourbon Restoration in Spain, Antonete Gálvez was granted amnesty and returned to his hometown. He even became friends with Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the leader of the Restoration, who saw Gálvez as an honest and brave man, despite his strong political views.

Roque Barcia did not flee on the frigate "Numancia." Just four days after Cartagena's surrender, he published a document condemning the cantonal rebellion, even though he had been one of its main leaders. He claimed he was in Cartagena because he couldn't leave and was a "prisoner." He then criticized the movement and its leaders, saying they were not good at governing. He stated that federalism was still developing and that he recognized the current government. According to José Barón Fernández, this act discredited Roque Barcia as a politician forever.

List of Cantons

| Federal Canton | Proclamation | Dissolution |

| Canton of Alcoy | 09/07/1873 | 13/07/1873 |

| Canton of Algeciras | 22/07/1873 | 08/08/1873 |

| Canton of Alicante | 20/07/1873 | 23/07/1873 |

| Canton of Almansa | 19/07/1873 | 21/07/1873 |

| Canton of Andújar | 22/07/1873 | ? |

| Canton of Bailén | 22/07/1873 | ? |

| Canton of Béjar | 22/07/1873 | ? |

| Canton of Cádiz | 19/07/1873 | 04/08/1873 |

| Canton of Camuñas | ? | ? |

| Canton of Cartagena | 12/07/1873 | 13/01/1874 |

| Canton of Castellón | 21/07/1873 | 26/07/1873 |

| Canton of Córdoba | 23/07/1873 | 24/07/1873 |

| Canton of Granada | 20/07/1873 | 12/08/1873 |

| Canton of Gualchos | 23/07/1873 | ? |

| Canton of Huelva | ? | ? |

| Canton of Jaén | ? | ? |

| Canton of Jumilla | ? | ? |

| Canton of Loja | ? | ? |

| Canton of Málaga | 21/07/1873 | 19/09/1873 |

| Canton of Motril | 22/07/1873 | 25/07/1873 |

| Canton of Murcia | 14/07/1873 | 11/08/1873 |

| Canton of Orihuela | 30/08/1873 | ? |

| Canton of Plasencia | ? | ? |

| Canton of Salamanca | 24/07/1873 | ? |

| Canton of San Fernando | ? | ? |

| Canton of Sevilla | 19/07/1873 | 31/07/1873 |

| Canton of Tarifa | 19/07/1873 | 04/08/1873 |

| Canton of Torrevieja | 19/07/1873 | 25/07/1873 |

| Canton of Valencia | 17/07/1873 | 07/08/1873 |

Role of the International Workers' Association

There has been much debate about how much the International Workingmen's Association (AIT) was involved in the Cantonal Rebellion. Today, it seems clear that the AIT leaders did not directly plan the rebellion. The only places where internationalists took the lead, besides the 'Petroleum Revolution' in Alcoy, was in San Lúcar de Barrameda.

However, many individual "internationalists" did take part in the rebellion, especially in Valencia and Seville, where some joined the local Juntas. A letter from Francisco Tomás Oliver on August 5 confirmed this, noting that many internationalists participated in the cantonal movement, especially in cities like Valencia, Seville, Málaga, and Granada. He said their participation was spontaneous, without any prior agreement.

In a later letter, Tomás explained that the Alcoy uprising was a "purely working-class, revolutionary socialist movement," different from the cantonal rebellion, which he called "purely political and bourgeois." He stated that Seville and Valencia were the only two cities where internationalists succeeded, but he acknowledged their active role in other towns. As a result, the repression also affected internationalists, especially after Emilio Castelar formed his government.

On August 16, 1873, "The Federation," an AIT publication, explained why it believed the cantonal rebellion failed. It argued that the movement failed because it wasn't truly revolutionary. It said that simply shouting "Long live the federal republic!" wasn't enough; a revolution needed to destroy all government, organize work, and end the privileges of capital.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión cantonal para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión cantonal para niños