Carloctavismo facts for kids

Carloctavismo (also called carlosoctavismo or octavismo) was a special group within Carlism. Carlism was a political movement in Spain that wanted a different royal family to rule. Carloctavismo was most active between 1943 and 1953. This group believed that Carlos Pio de Habsburgo-Lorena y de Borbón (who they called Carlos VIII) should be the King of Spain. They also worked very closely with the government of Francisco Franco, known as Francoism.

Contents

The Start of Carloctavismo (1932–1943)

For about a hundred years, the Carlist movement had a clear line of kings. But in the early 1930s, it looked like their royal family would soon end. The current Carlist leader, Don Alfonso Carlos, was 82 years old and had no children. This meant Carlists did not know who their next king would be.

Some Carlists worried that Don Alfonso Carlos might make a deal with another royal family branch, the Alfonsists. These Carlists felt that such a deal would betray their history. Their ancestors had fought and died to oppose the Alfonsist family.

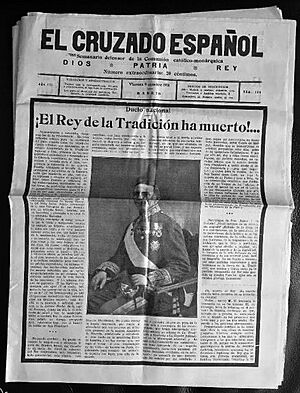

A newspaper in Madrid called El Cruzado Español was very against this deal. They wanted Don Alfonso Carlos to choose his heir while he was still alive. At first, they thought Renato de Borbón-Parma could be the heir. A group led by Juan Pérez Nájera wrote to Don Alfonso Carlos in 1932. He met them but did not agree to their demands.

The group, known as the Cruzadistas, then changed their plan. They wanted a big Carlist meeting to decide the heir. They did not name a candidate openly. However, they were already talking to Doña Blanca, the daughter of a famous Carlist king, Carlos VII. They were interested in her youngest son, Carlos Pio, who lived in Barcelona.

In 1933, the Cruzadistas faced problems. Carlos Pio moved to Vienna after a brief arrest. Don Alfonso Carlos was tired of their pressure and removed the Cruzadistas from the Carlist movement. In 1934, he even made Carlos Pio say he had no right to the throne.

But the Cruzadistas were now free to act on their own. They formed a group called Núcleo de la Lealtad (meaning "Core of Loyalty"). In 1935, they held a meeting in Zaragoza. They said that Doña Blanca could pass on royal rights to her sons. Doña Blanca at first said she was not part of this.

However, her mind changed in January 1936. Don Alfonso Carlos decided to name a distant relative, Javier de Borbón-Parma, as a future leader (regent). In May 1936, Doña Blanca then said that after her uncle died, she would accept her royal rights and pass them to her youngest son, Carlos Pio.

When the Civil War began, the Cruzadistas were allowed back into the main Carlist group, the Comunión Tradicionalista. Some Carlist soldiers, called Requetés, even shouted Carlos Pio's name as their future king, calling him Carlos VIII. Carlos Pio wanted to join the Carlist troops, but Don Alfonso Carlos told him no. Later, Francisco Franco also politely refused his request.

After 1937, Carlos Pio and the Cruzadistas stopped their political activities. The main goal for Carlists was to protect their identity from Franco's government. Franco wanted to combine all political groups into one new state party.

After Franco's side won the war in 1939, the former Cruzadista supporters spoke up again. But in 1940, Doña Blanca said she was loyal to the regent, Don Javier, and ignored her promise from 1936. However, the idea of Carlos Pio as king did not die out. Many Carlists who did not like Don Javier's strong opposition to Franco started to see Carlos Pio as another choice for king.

Spain in 1943

After 1936, Franco's new government did not want to talk about who would be the next king. In the early 1940s, more people started pushing for a king. The Alfonsist leader, Don Juan, had tried to work with Hitler to overthrow Franco. But by 1943, he changed his mind and wanted a king who would rule with a constitution. In March 1943, he wrote to Franco, saying the government was only temporary and a king should be restored quickly. Franco replied that a king would not be chosen based on old family lines.

In June, Franco faced a big challenge. 26 members of the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes, signed a letter. They asked for Spain's old government systems to be brought back. In August, Don Juan sent another strong message. The Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde, quickly warned that any future king must be a Traditionalist, not a Liberal. In September 1943, most top army generals signed a letter demanding the king be restored. Franco had a very hard time convincing them to obey him.

The world situation for Franco's government changed a lot between 1942 and 1944. At first, other countries, especially the Allies (like the US and Britain), just wanted to stop Spain from joining the Axis (Germany, Italy). They did not want to upset Franco by criticizing his government.

But by 1943, things were different. The Allies had landed in North Africa, Germany was losing battles, and Mussolini (Italy's leader) had fallen. Spain joining the war was no longer a worry. The Allies started to see Spain as an unfriendly country. American news showed Spain as a fascist country, and BBC radio broadcasts were anti-Franco.

However, the Allies mainly wanted to stop Spain from sending supplies to Germany. By late 1943, the Allies demanded that Spain stop these shipments. They threatened to stop all fuel supplies to Spain. This threat worked, and Spain's economy suffered greatly in early 1944. People and politicians in Britain and the United States were strongly against Franco. By late 1943, Franco even thought the Allies might invade Spain.

Because of the growing pressure from within Spain and from other countries, Franco decided his government needed to change. After a political event called the Begoña crisis, Franco started to make big changes in 1943. He made the Falangist party less important. Instead, he focused more on Catholic and traditional values. He also tried to show that Spain was different from the Axis countries. He created a parliament to make his government look less like a dictatorship.

Most importantly, Franco started to think seriously about bringing back a king. Franco liked to keep different political groups balanced. So, he decided to try two paths at once. He invited Don Juan, the Alfonsist leader, to live in Spain, but Don Juan refused. Franco ignored Don Javier, the Carlist regent, who was first stuck in France and then arrested by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp. But Carlos Pio was welcomed in Spain.

Carlos Pio's Rise (1943–1948)

Carlos Pio had been living in Italy since 1938. It is not clear if he or Franco's government started his move back to Spain in early 1943. But most experts agree that Franco must have approved it when Carlos Pio's family settled in Barcelona in March.

Jesús Cora y Lira, who was Carlos Pio's main supporter, often visited Franco's palace. He agreed with Franco's team and some important Falangists that he would start promoting Carlos Pio. In May, Doña Blanca again said she would pass her royal rights to her youngest son. So, on June 29, 1943, Carlos Pio issued a statement, saying he should be the king. This document did not use the name Carlos VIII and only mentioned Franco once, saying he fought "dangers surrounding the Homeland."

Carlos Pio's supporters, now called Carloctavistas, were again removed from the main Carlist group. They started to organize themselves. General Cora y Lira became Carlos Pio's secretary. Carlos Pio also created his own council and started groups like the Comunión Católico-Monárquica and Juventudes Carlistas. These groups were careful not to break the rule that only Franco's party, FET, was allowed.

Carlos Pio could travel freely, often with police protection, and began touring Spain. This campaign, from 1944 to 1946, aimed to promote him without getting huge numbers of followers. The Carloctavistas supported Franco's government and ignored their differences with traditional Carlist ideas. Many of their flyers had the slogan "Franco y Carlos VIII."

Franco's government allowed this but did not openly support it. Government officials did not go to Carloctavista meetings. However, some Carloctavista supporters did get important government jobs. Newspapers were allowed to mention Carlos Pio in social news, but not in political news. Still, it was unusual that Carlos Pio was the only royal claimant who could travel Spain and openly promote himself.

The Carloctavistas had conflicts with two other groups:

- The main Carlists, who were loyal to Don Javier and strongly against Franco.

- Another Carlist group that worked with Franco and wanted to make a deal with Don Juan.

Sometimes these conflicts led to fights, like in December 1945 in Pamplona. The Carloctavistas gained strength because many Carlists were tired of being semi-secret. They were also annoyed by Don Javier's long and seemingly ineffective leadership. However, many Carlists also saw Carlos Pio as a puppet of Franco, used only to cause confusion.

Even so, the Carloctavistas, who were first seen as "elites with no supporters," gained a lot of backing. They did not become stronger than Don Javier's supporters, but some writers say they might have been equally popular. They had the most support in Navarre and Catalonia. They also controlled some Carlist newspapers. Important Carloctavista supporters included Esteban Bilbao, Antonio Iturmendi, Joaquín Bau, Jaime del Burgo, Juan Granell Pascual and Antonio Lizarza Irribaren. Many Carloctavistas were well-known politicians in their local areas.

The Carloctavista movement reached its peak in 1947–1948. At this time, other countries were very critical of Spain. Franco decided to take a formal step towards bringing back a king. He started a campaign for the Ley de Sucesión en la Jefatura del Estado (Law of Succession in the Head of State). This law officially declared Spain a monarchy for the first time. The law gave Franco almost complete power to choose the future king and did not mention any old family claims. This made both Don Juan and Don Javier very angry, and they sent protest letters to Franco.

Carlos Pio fully supported this law from the beginning. He appeared in propaganda for the 1947 referendum (a public vote). He was carefully shown in official media like weekly newsreels. At that time, some people thought the law might have been written with Carlos VIII in mind.

Decline of Carloctavismo (1948–1953)

By 1947–48, world politics changed. Spain was no longer seen as an enemy from Second World War. Instead, it was starting to be seen as a possible ally in the new Cold War. This meant that making the government look more like a monarchy was less urgent for Franco.

Also, Franco's use of Carlos Pio might have influenced Don Juan. Don Juan finally agreed to meet Franco. In August 1948, they decided that Don Juan's 10-year-old son, Juan Carlos, would be sent to Spain for his education. This happened in November that year.

This changed Carlos Pio's position greatly. Even though no promises were made about Don Juan's son, and he could not become king until 1968, Franco's government had taken a small but clear step towards bringing back an Alfonsist king.

Another problem for Carlos Pio came in mid-1949. His wife, Christa Satzger, left him and got a quick divorce in Reno. This hurt his image as a good Catholic family man. Even though he asked the Church to say his marriage was invalid so he could remarry, it became unlikely he would have a legitimate male child soon, or at all.

The Carloctavistas continued to support their cause by organizing royal trips, meetings, and congresses. In 1948, the Juventudes Carlistas published a program booklet. Its long title explained their ideas: El carlismo no quiere ni una Monarquía absoluta, ni una Monarquía liberal, ni un Estado totalitario, ni un Estado policíaco (Carlism wants neither an absolute monarchy, nor a liberal monarchy, nor a totalitarian state, nor a police state). This work presented a traditional Carlist view, focusing on monarchy, Catholic faith, regional rights, and community groups. It did not mention Franco's leadership and did not support the Falangist national-syndicalism. When talking about social issues, it focused on worker organizations. What made it different from traditional Carlism was that it tried to be more modern. It even had some ideas about society being open to everyone, which was new for traditional Carlism.

The Carloctavista group started to divide internally. In 1950, new groups appeared that did not agree with Cora y Lira's strategy of fully supporting Franco. Two years later, the Frente Nacional Carlista was formed. It is not clear if Carlos Pio knew about these new groups.

In 1950, Francisco Javier Lizarza Inda published La sucesión legítima a la corona de España, a book explaining the Octavista claim. It was re-published in 1951 but only convinced those who already believed. After many years of asking, Franco finally met Carlos Pio in 1952. This was their only personal meeting. Franco probably did this to counter Don Javier, who had just ended his role as Carlist regent and claimed the throne himself. There is no record of their one-hour talk, but Carlos Pio was very happy afterward. Franco also accepted an award created by Carlos VIII, the Orden de San Carlos Borromeo, later that year.

Franco's government never officially supported Carlos Pio's claim. In late 1953, Carlos Pio died suddenly from a brain hemorrhage. He was a heavy smoker but seemed to be in good health. This led to rumors of an assassination, but there was no proof.

His funeral was surprisingly important. Franco did not attend, but many other top government officials did. Even the popular newspaper ABC, which had almost never mentioned Carlos VIII for ten years, now felt safe to report his death. A two-page article praised him for being against communism and talked about his love for motor sports. But it did not say a single word about his claim to the throne.

After Carlos Pio (after 1953)

After Carlos Pio died, his supporters, the Carloctavistas, were very confused. Most of them felt their cause was hopeless and left politics. A few started to get closer to Don Javier's supporters. Almost none joined Don Juan's supporters.

Those who still believed in the Octavista idea focused on Carlos Pio's relatives. Cora y Lira supported Carlos Pio's older brother, Don Antonio. In early 1954, Cora convinced most of the Comunión Católico-Monárquica leaders to accept Don Antonio as Carlos IX. Don Antonio was surprised by this. After thinking about it, he said later that year that he would not take part in politics. Most Carloctavista leaders were very discouraged. One of them said, "we are, dear friends, in the most absolute and complete ridiculous situation."

However, some people were determined to continue. Jaime del Burgo suggested that Carlos Pio's oldest daughter, 14-year-old Doña Alejandra, be declared a "temporary standard-bearer." This way, she could pass on royal rights to her future son. Cora y Lira promoted Don Antonio's 17-year-old son, Don Domingo. He started raising money to help Don Domingo settle in Spain. But in 1955, Don Antonio, who might have been Carlos IX, angrily removed Cora for "abusing his power."

Don Antonio changed his mind in 1956. He officially declared himself the heir to the Carlist throne and named Lizarza Iribarren as his representative in Spain. The confusion grew when another brother of Carlos Pio, Don Francisco José, challenged Don Antonio that same year. Don Francisco José claimed royal rights for himself, and Cora y Lira became his main supporter.

For the next few years, the two brothers, neither of whom lived in Spain, promoted their own claims. Don Antonio issued royal statements in the late 1950s. Don Francisco José fought legal battles in Spanish courts in the early 1960s about noble titles. In 1961, Don Antonio retired from public life. Lizarza tried to formally bring Don Antonio's supporters back into the main Carlist group. In 1962, many local leaders, but not Lizarza himself, decided to join Don Javier's supporters. Don Francisco José did less and less after the mid-1960s. His cause was supported by a few newspapers, mostly ¡Carlistas!. In 1969, a newspaper called Pueblo published a long interview with Don Francisco José. This was probably a last-minute effort by the Falangist party to stop Don Juan Carlos from being officially named the future king.

The Octavistas faced a big blow in 1969 when their most dedicated supporter, Cora y Lira, died. Don Francisco José passed away in 1975, and Don Antonio in 1987. By the mid-1980s, most Carloctavistas were very small groups. They joined a united Traditionalist organization called Comunión Tradicionalista Carlista. This new group did not support any specific royal claimant.

Today, Carloctavistas are mostly known through a few websites. These websites feature Don Antonio's son, Don Domingo, as the rightful King of Spain. Don Domingo, who lives mostly in New York, decided to claim the throne himself. When he was in his 20s, he knew nothing about the Carlist cause and did not care about it. But now he calls himself king and sometimes issues documents like Proclamación de Don Domingo de Habsburgo-Borbón y Hohenzollern, Rey legitimo de España (Proclamation of Don Domingo of Habsburg-Bourbon and Hohenzollern, Legitimate King of Spain). Carlos Pio's oldest daughter lives in Barcelona, and the other lives in New York. Since the early 1960s, they have had no connection with Carlism.

See also

In Spanish: Carloctavismo para niños

In Spanish: Carloctavismo para niños

- Carlism

- Don Carlos

- Don Javier

- Don Juan

- Don Antonio

- Don Francisco Jose

- Don Domingo

- Jesús Cora y Lira

- Jaime del Burgo Torres

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |