Carlos Mesa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carlos Mesa

OCA OSP OMAA OMM

|

|

|---|---|

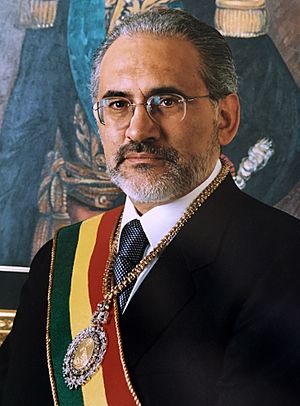

Official portrait, 2004

|

|

| 63rd President of Bolivia | |

| In office 17 October 2003 – 9 June 2005 |

|

| Vice President | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada |

| Succeeded by | Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé |

| 37th Vice President of Bolivia | |

| In office 6 August 2002 – 17 October 2003 |

|

| President | Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada |

| Preceded by | Jorge Quiroga (2001) |

| Succeeded by | Álvaro García Linera (2006) |

| Leader of Civic Community | |

| Assumed office 13 November 2018 |

|

| Preceded by | Alliance established |

| Official Representative of Bolivia for the Maritime Claim |

|

|

Ad honorem

|

|

| In office 28 April 2014 – 1 October 2018 |

|

| President | Evo Morales |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position dissolved |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Carlos Diego de Mesa Gisbert

12 August 1953 La Paz, Bolivia |

| Political party | Revolutionary Left Front (2018–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

Independent (before 2018) |

| Spouses |

Patricia Flores Soto

(m. 1975; div. 1978)Elvira Salinas Gamarra

(m. 1980) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Education |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of awards and honors |

| Signature |  |

Carlos Diego de Mesa Gisbert (born 12 August 1953) is a Bolivian historian, journalist, and politician. He served as the 63rd president of Bolivia from 2003 to 2005. Before that, he was the 37th vice president of Bolivia from 2002 to 2003.

Mesa became famous as a journalist and TV host. In 2002, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada asked Mesa to be his vice-presidential running mate. They won the election, but soon disagreed on how to handle major protests. When Sánchez de Lozada resigned in 2003, Mesa became president.

As president, Mesa faced many challenges. He held a national vote on how to use Bolivia's natural gas, which passed. However, protests continued, and he struggled to work with the country's legislature. He resigned in 2005 to help calm the political situation.

After his presidency, Mesa returned to journalism. In 2014, President Evo Morales asked him to be the international spokesman for Bolivia's effort to gain access to the Pacific Ocean. This work made him popular again, and he ran for president in 2019 and 2020. He lost both elections but became the leader of the main opposition group in Bolivia's government.

Contents

Early Life and Career

A Young Life in Bolivia and Spain

Carlos Mesa was born on August 12, 1953, in La Paz, Bolivia. His parents, José de Mesa and Teresa Gisbert, were famous Bolivian architects and historians. He has three younger siblings.

Mesa went to San Calixto School in La Paz. In 1970, he moved to Spain and finished high school in Madrid. He then studied at the Complutense University of Madrid. After three years, he returned to Bolivia and earned a degree in literature from the Higher University of San Andrés (UMSA) in 1978.

Career as a Journalist

Mesa started his career in journalism while he was still in college. In 1976, he helped start the Bolivian Cinematheque, an archive for films. He also worked in radio, hosting and producing news shows.

His big break came in television. In 1983, he began hosting a popular interview show called De Cerca. On the show, he interviewed important political figures. The show was a huge success and made him a well-known person across Bolivia.

In 1990, Mesa co-founded a TV production company called Associated Journalists Television (PAT). PAT produced a news program that aimed to be independent from government control. It became one of the most important news sources in the country.

Vice Presidency (2002–2003)

Entering Politics

For years, Mesa was asked to enter politics, but he always said no. He preferred being an independent journalist. However, in 2002, former president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada asked him to be his running mate for vice president.

Sánchez de Lozada's team believed Mesa's popularity could help them win. After thinking it over, Mesa accepted the offer. He wanted to help solve Bolivia's economic problems and fight corruption.

The election in June 2002 was very close. Sánchez de Lozada and Mesa won with 22.5% of the vote. They formed a coalition with another party to get enough support in Congress. On August 6, 2002, Mesa became the Vice President of Bolivia.

A Difficult Vice Presidency

As vice president, Mesa focused on fighting corruption. He created a special team to investigate dishonest practices in the government. However, he often disagreed with President Sánchez de Lozada.

In February 2003, the government announced a new tax that led to major riots. The situation became even more serious in October 2003 during the Gas Conflict. This was a series of huge protests over the government's plan to export natural gas through Chile.

When the government used the military against protesters, many people were killed. Mesa strongly disagreed with this violence. On October 13, he announced he could no longer support the president. He did not resign as vice president, because he wanted to ensure there was a clear successor if the president left office. Four days later, Sánchez de Lozada resigned, and Mesa became president.

Presidency (2003–2005)

Taking Office in a Crisis

Mesa became president with a lot of public support. He promised to address the issues that caused the protests. This included holding a vote on the gas export plan and creating a new constitution. This plan was called the "October Agenda."

He formed a cabinet of experts who were not part of any political party. This made it hard to work with Congress, which was controlled by the traditional parties.

One of his first acts was to visit El Alto, the city at the center of the protests. He promised justice for the victims of the violence. He also asked Congress to investigate Sánchez de Lozada and his government for their actions.

Key Policies and Challenges

The Economy and Government

Mesa's government faced a big economic challenge. To save money, he cut his own salary and the salaries of other top officials. He also introduced a new tax on large bank transactions. These actions helped reduce the country's budget deficit.

The Gas Referendum

| Results of the 2004 gas referendum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 18 July 2004 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Nohlen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On July 18, 2004, Mesa held a national referendum (a special public vote) on natural gas. The vote had five questions about how Bolivia should manage and sell its gas. All five questions passed with strong support. The results were a major victory for Mesa's government.

After the vote, Mesa tried to pass a new hydrocarbons law. However, he could not agree with Congress on the details. The final law, passed in May 2005, was not what he wanted.

Regional Autonomy

Another major issue was the demand for more autonomy, or self-rule, from regions like Santa Cruz. Mesa supported the idea of letting regions elect their own leaders, called prefects.

In January 2005, after large protests in Santa Cruz, Mesa agreed to hold a referendum on autonomy. He also issued an order to allow for the election of prefects.

Resignation

Despite some successes, Mesa struggled to govern. He faced constant pressure from protesters and a difficult Congress. In March 2005, he offered to resign, but Congress rejected it.

By June 2005, the country was paralyzed by strikes and roadblocks. Unwilling to use force against protesters, Mesa resigned for good on June 6. To avoid more conflict, he asked the leaders of Congress to also give up their right to become president.

This allowed Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, the head of the Supreme Court, to become the new president. Rodríguez Veltzé's main job was to organize new elections.

After the Presidency

Return to Journalism and Public Life

After leaving office, Mesa returned to his work as a journalist and writer. He wrote a book about his time as president and created a documentary series about Bolivian history.

In 2014, President Evo Morales gave him an important job. Mesa became the international spokesman for Bolivia's legal case against Chile. Bolivia was asking the International Court of Justice to require Chile to negotiate giving Bolivia access to the sea.

Mesa traveled the world to explain Bolivia's position. This work made him a popular figure again. In 2018, the court ruled that Chile was not required to negotiate. Mesa urged Bolivians to accept the decision.

Return to Politics

Running for President

Mesa's work on the maritime case made him a leading opposition figure. In October 2018, he announced he would run for president in the 2019 election. He formed a new political alliance called Civic Community.

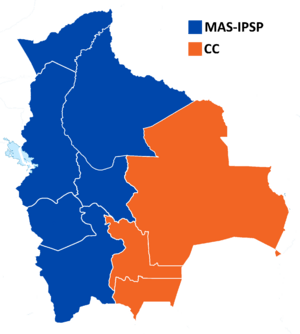

The election was held on October 20, 2019. Early results suggested that Mesa and President Morales would face each other in a second-round runoff. However, the official count was suddenly stopped. When it resumed, it showed Morales had won enough votes to avoid a runoff.

Mesa and his supporters claimed the election was fraudulent. This led to massive protests across the country. The crisis ended with Morales resigning from the presidency in November 2019. A temporary government was formed, and new elections were scheduled.

2020 Election

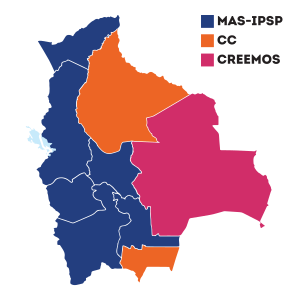

Mesa ran for president again in the new election held in October 2020. He faced Luis Arce, the candidate from Morales's party, MAS.

Arce won the election in the first round with over 55% of the vote. Mesa came in second with about 29%. He accepted the results and became the leader of the largest opposition group in the legislature.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Carlos Mesa para niños

In Spanish: Carlos Mesa para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |