Bolivian gas conflict facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bolivian gas conflict |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pink tide | |||

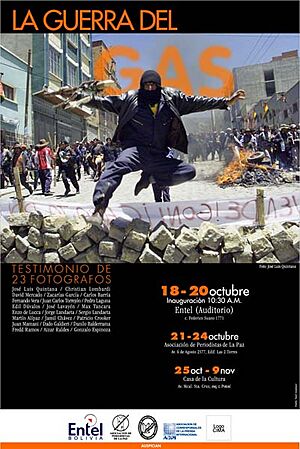

2003 demonstrations against president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. "The gas is ours by right, to recover it is our duty."

|

|||

| Date | September 2003 - May 2006 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals | Nationalization of natural gas | ||

| Methods |

|

||

| Resulted in | Protestor victory

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Bolivian gas conflict was a big social problem in Bolivia that became very serious in 2003. It was mainly about how the country's huge natural gas supplies should be used. This conflict also includes protests in 2005 and the election of Evo Morales as president. Before this, Bolivia had similar protests, like the Cochabamba Water War in 2000, which was against selling off the city's water system to private companies.

The conflict started because people were unhappy with the government's plans for natural gas. They also disliked policies about growing coca plants, corruption, and the government's violent response to strikes. Looking back further, these problems connect to Bolivia's history since the 15th century. Since then, its natural resources, like the silver mines of Potosí, have often been controlled by outside groups.

The "Bolivian gas war" got very intense in October 2003. This led to President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (also known as "Goni") resigning. Strikes and road blockades by indigenous groups and worker unions (like the COB) stopped the country. The Bolivian army used force, and about 60 people died in October 2003. Most of them were from El Alto, a city near La Paz.

The government broke apart, and Goni had to resign and leave the country on October 18, 2003. His vice president, Carlos Mesa, took over. Mesa held a vote on the gas issue on July 18, 2004. In May 2005, because of more protests, the Bolivian congress passed a new law. This law increased the money the state got from natural gas. However, protesters, including Evo Morales and Felipe Quispe, wanted the gas resources to be fully owned by the state. They also wanted Bolivia's indigenous majority, mostly Aymaras and Quechuas, to have more say in politics.

On June 6, 2005, Mesa was forced to resign. Tens of thousands of protesters blocked roads to La Paz every day. Morales' election at the end of 2005 made social movements happy. He was the leader of the MAS party. He strongly opposed exporting gas without processing it in Bolivia first. On May 1, 2006, President Morales signed a rule saying all gas reserves would be owned by the state. He said, "the state takes back ownership, control, and full power" over these resources. This announcement was cheered in La Paz's main square. Vice President Álvaro García Linera told the crowd that the government's gas money would jump from US$320 million to US$780 million in 2007. This continued a trend where gas money had grown almost six times between 2002 and 2006.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

Bolivia's Gas Riches

Bolivia has huge natural gas reserves, the second largest in South America after Venezuela. After the national oil company YPFB was privatized, new explorations showed that Bolivia had six times more natural gas than previously thought. The state-owned company couldn't afford to explore for more gas. Most of these gas reserves are in the southeastern Tarija Department.

From 1996 to 2002, the estimated gas reserves grew much larger. These reserves became the main reason for foreign investment in Bolivia. This was especially true as tin mining became less important.

Bolivia sells its natural gas to Brazil and Argentina. For example, Brazil pays about $3.25 for a certain amount of gas. In comparison, gas prices in the US were much higher.

In 1994, a deal was made with Brazil. Two years later, in 1996, the 70-year-old state-owned company Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales de Bolivia (YPFB) was privatized. Building the Bolivia-Brazil gas pipeline cost US$2.2 billion.

Plans for Exporting Gas

A group of companies called Pacific LNG was formed to use the new gas reserves. This group included British companies BG Group and BP, and Spain's Repsol YPF. Repsol, Petrobras, and TotalEnergies are the main companies in Bolivia's gas industry.

There was a plan to build a US$6 billion pipeline to the Pacific Ocean. The gas would be processed and turned into liquid gas there. Then it would be shipped to Mexico and the United States. This plan would use a Chilean port, like Iquique. Many Bolivians strongly opposed the 2003 deal made by President Lozada. This was partly due to strong national feelings. Bolivia still felt upset about losing its coast to Chile in the War of the Pacific in the late 1800s.

Government leaders hoped to use the gas money to help Bolivia's struggling economy. They said the money would only be used for health and education. But opponents argued that under the current law, Bolivia would only get 18% of the future profits from exporting raw gas. This would be about US$40 million to US$70 million per year. They said exporting gas so cheaply was just another example of foreign companies taking Bolivia's natural resources. They wanted a plant built in Bolivia to process the gas. They also said Bolivia's own energy needs should be met before any gas was exported.

Disagreement Over Pipeline Route

The argument started in early 2002. President Jorge Quiroga suggested building the pipeline through neighboring Chile to the port of Mejillones. This was the shortest way to the Pacific Ocean. However, many Bolivians dislike Chile deeply. This is because Bolivia lost its Pacific coastline to Chile in the War of the Pacific (1879–1884).

Bolivians began protesting against the Chilean option. They argued that the pipeline should go north through the Peruvian port of Ilo. This port is 260 km further from the gas fields than Mejillones. Even better, they said, the gas should be processed in Bolivia first. Chile estimated that the Mejillones route would be $600 million cheaper. Peru, however, said the cost difference would be no more than $300 million. Bolivians who supported the Peruvian option said it would also help the economy of northern Bolivia.

The Peruvian government offered Bolivia a special economic zone for 99 years at Ilo. This would allow Bolivia to export gas freely and manage a 10 km² port area.

President Jorge Quiroga delayed the decision before leaving office in July 2002. He left this difficult issue to the next president. After winning the 2002 election, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada preferred the Mejillones option. But he didn't make an "official" decision. The Gas War led to his resignation in October 2003.

Protests Grow Stronger

The social conflict got worse in September 2003. Protests and road blockades stopped large parts of the country. This led to more and more violent fights with the Bolivian army.

Bolivia's indigenous majority led the protests. They accused President Sánchez de Lozada of following the US government's "war on drugs." They also blamed him for not making life better in Bolivia. On September 8, 650 Aymara people started a hunger strike. They were protesting the arrest of a village leader.

On September 19, groups against the pipeline gathered 30,000 people in Cochabamba and 50,000 in La Paz. The next day, six Aymara villagers, including an eight-year-old girl, were killed in a fight in Warisata. Government forces used planes and helicopters to get around the strikers. They evacuated hundreds of tourists who were stuck by road blockades.

After the shootings, Bolivia's Labor Union (COB) called a general strike on September 29. This strike stopped the country with road closures. Union leaders said they would continue until the government changed its mind. Aymara community groups, with slingshots and old guns, drove the army and police out of Warisata.

As protests continued, people in El Alto, a large indigenous city near La Paz, blocked main roads to the capital. This caused serious shortages of fuel and food. They also demanded that Sánchez de Lozada and his ministers resign. Protesters also spoke out against the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement.

Martial Law in El Alto

On October 12, 2003, the government declared martial law in El Alto. This happened after 16 people were shot by police. Many more were hurt in violent clashes. This occurred when oil trucks, guarded by police and soldiers with tanks, tried to break through a blockade.

On October 13, Sánchez de Lozada's government stopped the gas project. They said it would be on hold "until consultations have been conducted [with the Bolivian people]." However, Vice President Carlos Mesa criticized the "excessive force" used in El Alto, where 80 people died. He then stopped supporting Sánchez de Lozada. The Minister of Economic Development also resigned.

The United States Department of State supported Sánchez de Lozada on October 13. They asked Bolivia's leaders to support democracy. They said the international community would not accept any interruption of democratic order.

On October 18, Sánchez de Lozada's government lost crucial support. He was forced to resign and was replaced by his vice president, Carlos Mesa. The strikes and roadblocks were lifted. Mesa promised that no civilians would be killed by police or army forces during his time as president. He kept this promise despite much unrest.

One of Mesa's first actions was to promise a vote on the gas issue. He also appointed several indigenous people to government jobs. On July 18, 2004, Mesa held a vote on gas nationalization. On May 6, 2005, the Bolivian Congress passed a new law. This law raised taxes on foreign companies' oil and gas profits from 18% to 32%. Many protesters felt this law was not enough. They demanded that the gas and oil industry be fully owned by the state.

The 2005 Hydrocarbons Law

On May 6, 2005, the new Hydrocarbons Law was approved by the Bolivian Congress. This law gave legal ownership of all gas and natural resources back to the state. It kept royalties at 18% but increased taxes from 16% to 32%. It also gave the government control over selling the resources. It allowed for ongoing government checks with yearly audits. The law also said that foreign companies had to talk with indigenous groups living on land with gas. The law stated that 76 contracts signed by foreign companies had to be re-negotiated within 180 days. Protesters argued that the new law did not do enough to protect natural resources from foreign companies. They demanded full state ownership of the gas and oil industry.

Because of the uncertainty over re-negotiating contracts, foreign companies almost stopped investing in the gas sector. Foreign investment nearly halted in the second half of 2005. Shortages of diesel, LPG, and natural gas began to appear. The social unrest in May–June affected the supply of gas products inside Bolivia. This made people feel that the gas supply could not be guaranteed.

Carlos Mesa Resigns in June 2005

The Protests

Over 80,000 people took part in the May 2005 protests. Tens of thousands of people walked from El Alto to La Paz every day. Protesters effectively shut down the city. They stopped transportation with strikes and blockades. They also fought with police in the streets. The protesters demanded that the gas industry be owned by the state. They also wanted changes to give more power to the indigenous majority. These were mainly Aymara people from the poor highlands. Police pushed them back with tear gas and rubber bullets. Many miners involved in the protests carried dynamite.

On May 24, 2005, more than 10,000 Aymara farmers from the highlands came into La Paz to protest. On May 31, residents of El Alto and Aymara farmers returned to La Paz. More than 50,000 people covered a huge area. The next day, the National Police decided not to stop the protests.

On June 2, as protests continued, President Mesa announced two plans. He wanted to calm both the indigenous protesters and the Santa Cruz autonomy movement. He called for elections for a new constitutional assembly and a vote on regional self-rule. Both were set for October 16. However, both sides rejected Mesa's call. Protesters in El Alto began to cut off gasoline to La Paz.

About half a million people protested in La Paz on June 6. President Mesa then offered to resign. Riot police used tear gas as miners set off dynamite near the presidential palace. A strike stopped all traffic. However, Congress could not meet for several days because of the protests. Many members could not physically attend. Senate President Hormando Vaca Díez decided to move the meetings to Bolivia's capital, Sucre. This was an attempt to avoid the protesters. Radical farmers took over oil wells owned by foreign companies. They also blocked border crossings. Mesa ordered the military to fly food into La Paz, which was completely blocked.

Vaca Diez and House of Delegates president, Mario Cossío, were next in line to become president. However, protesters strongly disliked them. They both said they would not accept the presidency. Instead, they promoted Eduardo Rodríguez, the Supreme Court Chief Justice, to the presidency. He was seen as fair and trustworthy. His government was temporary until new elections could be held. Protesters quickly left many areas.

Caretaker President Rodríguez put the Hydrocarbons Law into action. The new tax (IDH) was collected from companies. Some gas companies used international investment protection agreements. They started talks with Bolivia. This could lead to a court hearing at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). This court could force Bolivia to pay money to the companies.

Nationalization of Natural Gas

On May 1, 2006, President Evo Morales signed a decree. It stated that all gas reserves would be owned by the state. He said, "the state takes back ownership, control, and full power" over these resources. He kept his election promises. He said, "We are not a government of mere promises: we follow through on what we propose and what the people demand." The announcement was made on Labor Day.

Morales ordered the military and engineers of YPFB, the state firm, to take over energy facilities. He gave foreign companies a six-month "transition period" to re-negotiate contracts. If they didn't, they would be expelled. However, President Morales said that the nationalization would not mean taking property without payment. Vice President Álvaro García Linera said that the government's energy money would jump to $780 million next year. This was almost six times more than in 2002.

Among the 53 facilities affected were those of Brazil's Petrobras. Petrobras is one of Bolivia's largest investors. It controls 14% of the country's gas reserves. Brazil's Energy Minister, Silas Rondeau, called the move "unfriendly." He said it went against previous agreements. Petrobras, Spain's Repsol YPF, UK's BG Group Plc, and France's Total are the main gas companies in Bolivia.

Negotiations between the Bolivian government and foreign companies became intense. This was especially true in the week before the deadline of Saturday, October 28, 2006. On Friday, an agreement was reached with two companies, including Total. By the deadline on Saturday, the other ten companies, including Petrobras and Repsol YPF, also agreed. The full details of the new contracts were not released. But the goal of raising the government's share of money from the two major gas fields from 60% to 82% seemed to be met. The government's share from smaller fields was set at 60%.

Talks with the Brazilian company Petrobras were very difficult. Petrobras had refused to increase payments or become just a service provider. Because talks stalled, Bolivian energy minister Andres Soliz Rada resigned in October. He was replaced by Carlos Villegas. Evo Morales said, "We are obligated to live with Brazil in a marriage without divorce, because we both need each other." This showed how much Brazil needed Bolivian gas and how much Bolivia needed Petrobras for gas production.

Reaction

On December 15, 2007, the regions of Santa Cruz, Tarija, Beni, and Pando declared they wanted to be self-governing. They also worked to become fully independent from Bolivia's new constitution.

The Protesters

Miners

Miners from the Bolivian trade union Central Obrera Boliviana (COB) were very active in the protests. They had also protested against plans to privatize pensions. They were known for setting off very loud dynamite explosions during the protests.

Coca Farmers

Soon after the law passed, Evo Morales took a moderate stance. Morales is an Aymara Indigenous leader and a cocalero (coca farmer). He leads the opposition party Movement Towards Socialism (MAS). He called the new law "middle ground." However, as protests grew, Morales supported nationalization and new elections.

Protesters in Cochabamba

Oscar Olivera was a key leader in the 2001 protests in Cochabamba against water privatization. He also became a leading figure in the gas conflict. Protesters in Cochabamba, Bolivia's fourth largest city, blocked main roads. They called for a new assembly to write a constitution and for nationalization.

Indigenous and Peasant Groups in Santa Cruz

Indigenous people in the eastern lowland region of Santa Cruz also became active. They were involved in disputes over gas and oil nationalization. These groups include the Guaraní, Ayoreo, Chiquitano, and Guyarayos. They are different from the highland indigenous people (Aymara and Quechua). They have been active in land disputes. Their main organization is the "Confederacion de pueblos indigenas de Bolivia" (CIDOB). The CIDOB first supported MAS, the party of Bolivia's new president. But they later felt that the Bolivian government had misled them. The MAS, based in the highlands, was not willing to give them more say than previous governments.

Another smaller, more radical group is the "Landless Peasant Movement" (MST). This group is similar to the Landless Workers' Movement in Brazil. It is mainly made up of people who moved from western Bolivia. Recently, Guaraní people from this group took over oil fields run by Spain's Repsol YPF and the United Kingdom's BP. They forced these companies to stop production.

Felipe Quispe and Peasant Farmers

Felipe Quispe was an Aymara leader. He wanted control of the country to return from the "white elite" to the indigenous people. These people make up most of Bolivia's population. So, he supported an independent "Aymaran state." Quispe led the Pachakutik Indigenous Movement. This group won six seats in Congress in the 2002 Bolivian elections. He was also the secretary general of the United Peasants Union of Bolivia.

See also

- Cochabamba anti-privatization protests

- Geology of Bolivia

- Bolivian gas referendum, 2004

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |