Castleshaw Roman Fort facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Castleshaw Roman fort |

|

|---|---|

A ditch of Castleshaw Roman fort

|

|

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Roman fort |

| Town or city | Castleshaw Saddleworth Greater Manchester |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°34′59″N 2°00′11″W / 53.583°N 2.003°W |

| Completed | 79 |

The Castleshaw Roman fort was a small Roman military camp, also called a castellum, in the Roman province of Britannia (which is now England). Some people think it might be the site of an ancient village called Rigodunum, which belonged to the Brigantes tribe. But there is no real proof for this idea.

The remains of the fort are on Castle Hill, on the east side of the Castleshaw Valley. This hill is near Castleshaw in Greater Manchester. The first fort was built around 79 AD. It was used for about 15 years, then it was no longer needed in the 90s AD.

Later, a smaller fortlet was built in its place around 105 AD. A small town grew up around this fortlet. It might have been a place where the Roman army managed supplies and orders. But this fortlet was also left empty around 120 AD.

People have been studying this site since the 1700s. But the civilian town was only found in the 1990s. The fort, fortlet, and the town are all protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. This means they are very important historical sites and cannot be changed without permission.

Contents

Where is Castleshaw Roman Fort?

The Roman fort and fortlet at Castleshaw are located on a flat area of rock called Grindslow shale. This spot is on the eastern side of the Castleshaw Valley. It sits below Standedge, which is part of the Pennines mountains in northern England.

From the site, you can see clearly up and down the valley. However, higher ground surrounds it on all sides. It is a remote and open place. The fort was built along the main Roman road that connected Deva Victrix (modern-day Chester) to Eboracum (modern-day York).

This road crossed the Pennines at Standedge, where the land dips and narrows. This created an easy path to cross the mountains. The Castleshaw fort would have guarded this important crossing. The closest Roman forts were Mamucium (modern-day Manchester), about 26 kilometers (16 miles) to the west. There was also a fort at Slack, about 13 kilometers (8 miles) to the east. Both of these forts were on the same Roman road.

There might have also been a small fortlet or signal station at Worlow, between Slack and Castleshaw. The later fortlet at Castleshaw was built in the exact same spot as the first, larger fort.

History of the Roman Fort

Building the First Fort

The first fort at Castleshaw was made from earth (turf) and wood (timber). It was built around 79 AD. Its main job was to protect the Roman road that went from York to Chester.

Because the site is a protected monument, archaeologists haven't been able to dig up the whole fort. But earlier digs showed that the fort was built in two main stages. We know where some of the important buildings were. These include the granary (where food was stored), stables, the principia (the main headquarters building), and the praetorium (the commander's house). There were also six long, narrow buildings that might have been workshops or storage rooms.

This fort was quite small. It probably housed about 500 soldiers. These soldiers were part of an auxiliary cohort, which means they were non-Roman troops who helped the main Roman army. The fort stopped being used in the mid-90s AD. Instead of letting enemies use its defenses, the Romans deliberately damaged the fort. This made it unusable.

The Smaller Fortlet and Town

A new, smaller fortlet was built in 105 AD. It was also made from turf and timber. Even though it was on the same spot as the old fort, it didn't use the old foundations. This fortlet also had two building stages. The second stage, around 120 AD, included gates, an oven, a well, a granary, and a hypocaust (an underfloor heating system). It also had a workshop, barracks (where soldiers slept), a commander's house, a courtyard building, and possibly a latrine (toilet).

The barracks were built for 48 soldiers. Even with officers and staff, the total number of soldiers in the fortlet would have been less than 100. The fortlet's defenses were not meant to stop a huge army. They were designed to protect against small attacks or to hold off an enemy until more Roman soldiers could arrive.

A civilian settlement, or vicus, grew up around the fortlet in the early 100s AD. This town was probably home to people who traded with the soldiers or were connected to them. Since such a small group of soldiers (under 100) couldn't really support a whole town, some experts think the fortlet was a "commissary fortlet." This means it was a center for managing supplies and orders for a part of the Roman army. Soldiers would regularly come here to get their pay and orders, which would have helped the town grow.

The fortlet was abandoned in the mid-120s AD. The nearby forts at Manchester and Slack then took over its role. The civilian town was also left empty around the same time.

An ancient Greek writer named Ptolemy mentioned a town called Rigodunum, belonging to the Brigantes tribe, near Castleshaw. Rigodunum means "royal fort." While some have suggested Castleshaw is this place, there's no proof.

Stamps found on two Roman roof tiles (called tegulae) suggest that the fortlet got its supplies from a Roman army unit called the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum. This unit came from Pannonia (an area in modern-day Hungary and Austria). They might have even been stationed at Castleshaw at one point. Similar stamps have been found at the forts in Manchester, Slack, and Ebchester. This shows that these forts were connected.

After the Romans Left

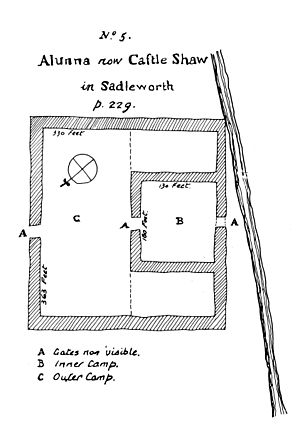

After the Romans left, the Castleshaw site was forgotten for a long time. Then, in 1752, a person who studied old things, named Thomas Percival, rediscovered it. The remains were in good enough shape for him to draw a map. He was happy to find "a double Roman camp." He also said that the Roman road from Manchester to the Pennines was "the finest remain of a Roman road in England that I ever saw."

The site has been damaged over the years by farming, especially in the 1700s and 1800s. This is because it's in one of the best-draining areas of the valley. In 1897, a local historian and poet, Ammon Wrigley, dug some trenches at the site. He didn't write down what he found, and unrecorded digging continued until 1907.

In 1907, the site was bought so that proper archaeological digs could be done. These digs took place from 1907 to 1908. They were led by Francis Bruton, who had also worked on the excavation of the Manchester Roman fort. The piles of dirt left from these 1907-08 digs were never leveled. This left misleading modern earthworks (mounds) inside the site.

More excavations were done by the University of Manchester from 1957–61 and 1963–64. Between 1984 and 1988, the Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit worked on digging and restoring the site. A group led by Professor Barri Jones, an expert on Roman Britain, helped organize the work. North West Water, who owned the site at the time, made sure the area would not be used for farming.

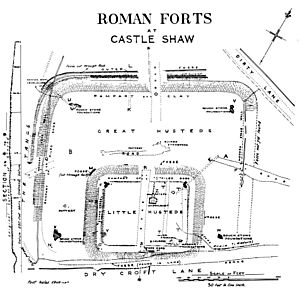

To make the site open to the public, the outlines of the fort and fortlet were marked out with low mounds. An education center was also set up nearby. The area outside the fort was explored for the first time in 1995–96. Archaeologists were looking for a civilian town (a vicus) connected to the fort. Surveys showed a triangular-shaped town to the south of the fort. This vicus is now also protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument, along with the fort and fortlet.

How the Fort was Laid Out

The first fort was rectangular. Its sides were about 115 meters (377 feet) long and 100 meters (328 feet) wide. It covered an area of about 1.2 hectares (3 acres). The smaller fortlet was built over the southern part of the fort. This makes it hard to know exactly what was underneath. However, we do know that the barracks were on the east side of the fort. The granary was on the north, and the principia (headquarters) and praetorium (commander's house) were to the southwest.

The fortlet was also rectangular, measuring about 50 meters (164 feet) by 40 meters (131 feet). It covered an area of about 1,950 square meters (0.48 acres). At first, people thought it had only one defensive ditch. But later investigations showed there were two ditches. These ditches were separated by a 2-meter (7-foot) wide flat area called a berm.

The inner ditch was 3.9 meters (13 feet) wide and 1.3 meters (4 feet) deep. The outer ditch was 2.5 meters (8 feet) wide and 0.9 meters (3 feet) deep. These were "Punic ditches," which means they were V-shaped with one side much steeper than the other. The ditches around the fortlet had an outer face at 27 degrees and an inner face at 69 degrees.

The rampart (a defensive wall or bank) behind the ditches is only about 0.5 meters (2 feet) high at its tallest point today. It was built from turf on top of sandy clay, with a foundation of rubble. The fortlet's ramparts to the south were built on top of the damaged ramparts of the older, larger fort. We don't know if the fortlet had corner towers. No evidence remains except for one posthole (a hole where a post once stood). Only the north and east corners are still in good condition. There were two gateways, one to the north and one to the south.

The civilian settlement is located to the south of the fortlet's defenses. We are not sure exactly how big the town was. But test digs have shown that it probably stretched about 12 meters (39 feet) from west to east. It also went between 25 meters (82 feet) and 35 meters (115 feet) to the south.

See also

In Spanish: Fuerte romano de Castleshaw para niños

In Spanish: Fuerte romano de Castleshaw para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |