Deva Victrix facts for kids

A model of Deva at the Grosvenor Museum, rendered as it probably appeared

|

|

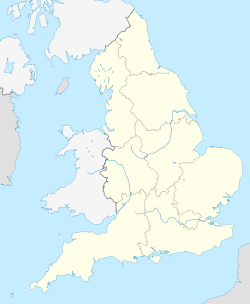

| Location | Chester, Cheshire, England |

|---|---|

| Region | Britannia |

| Coordinates | 53°11′29″N 02°53′34″W / 53.19139°N 2.89278°W |

| Type | Fortification and settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Mid 70s AD |

| Periods | Roman Imperial |

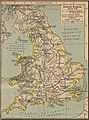

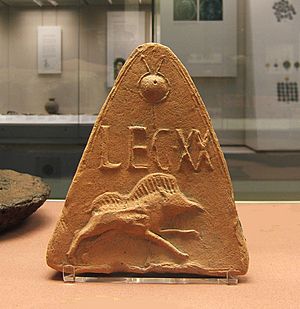

Deva Victrix, often just called Deva, was a large Roman army fortress and town. It was built in the Roman province of Britannia, which is now modern-day Chester, England. The fortress was first built in the 70s AD by a Roman army group called the Legio II Adiutrix. They were moving north to fight against a local tribe called the Brigantes. Over the next few decades, another army group, the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, completely rebuilt the fortress.

A town for civilians grew up around the fortress. This town was called a canaba. Chester's Roman Amphitheatre, located south-east of the fortress, is the biggest military amphitheatre found in Britain. Even after the Romans left, the civilian town stayed and eventually became the city of Chester we know today. There were also smaller settlements nearby, like Boughton, which supplied water to the fortress, and Handbridge, where they got sandstone for building. Handbridge is also home to Minerva's Shrine, a unique Roman shrine carved into rock that is still in its original spot.

The fortress itself had many important buildings. These included places for soldiers to sleep (barracks), storage for food (granaries), the army headquarters, and military baths. There was also a very unusual oval-shaped building. If it had been finished, it might have been the main office for the governor of Britain.

Contents

History of Deva Victrix

What does "Deva Victrix" mean?

The name Deva Victrix comes from the word "goddess." The Roman fortress was named after the goddess of the River Dee. In Latin, "goddess" is dea or diva.

Another idea is that the Romans simply used the British name for the river. The word "victrix" in the name means "victorious" in Latin. It was taken from the name of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix, the army group based at Deva. The name for the city of Chester comes from the Latin word castrum, which means "fort" or "army camp." This is why many English cities that started as Roman camps have names ending in "-chester" or "-caster."

How was the fortress built?

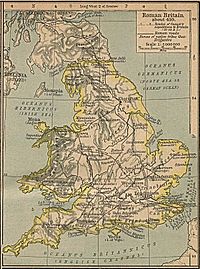

According to an ancient geographer named Ptolemy, Deva was in the land of the Cornovii tribe. Their land was next to the Brigantes in the north and the Ordovices in the west. When the Romans' peace treaty with the Brigantes failed, the Romans decided to conquer the area.

The Romans needed a new military base as they expanded north. Chester was a great spot for a fortress because it controlled access to the sea through the River Dee. It also helped separate the Brigantes from the Ordovices. So, the Legio II Adiutrix was sent to Chester in the mid-70s AD to start building the fortress.

The fortress was built on a high sandstone area, overlooking the river crossing and a natural harbor. The bend in the River Dee protected it from the south and west. The river was deep enough for boats up to this point, so building the fortress here made it easy to reach the harbor. The fortress needed a lot of water, about 2.4 million liters a day! This water came from natural springs in Boughton, about 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) to the east.

Lead pieces found in Chester suggest that building started around 74 AD. Any older military buildings on the site were taken down to make way for the new fortress. The first buildings were made of wood, which was quicker to build. Later, they were slowly replaced with stronger buildings made from local sandstone. To protect the fortress, there was a 6-meter (20-foot) wide rampart and a ditch 3 meters (10 feet) wide and 1.5 meters (5 feet) deep. The rampart was made of turf, sand, clay, and logs.

The fortress was shaped like a rectangle with rounded corners, similar to a playing card. It had four gates: north, east, south, and west. It covered about 25 hectares (62 acres), making it the largest fortress built in Britain during the 70s AD. A huge amount of timber was used in the first stage of building. The fortress included barracks, granaries (food stores), headquarters, and baths.

The Legio XX Valeria Victrix takes over

In 88 AD, the Emperor Domitian moved the Legio II Adiutrix to a different area. The Legio XX Valeria Victrix then came to Deva Victrix. They left a fort they were building in Scotland to come here. When they arrived, they started rebuilding Deva, first with timber and then with stone by the end of the 1st century. The new stone fortress walls were 1.36 meters (4.5 feet) thick at the bottom. There were 22 towers along the walls, about 60 meters (200 feet) apart. The defensive ditch was also re-dug, making it 7.5 meters (25 feet) wide and 2.45 meters (8 feet) deep. A lot of stone was used for these new defenses. The wooden barracks were replaced with stone buildings of similar size.

During the 2nd century, some soldiers from the Legio XX Valeria Victrix helped build Hadrian's Wall. This meant some parts of the Deva fortress were left empty or fell apart. In 196 AD, the legion likely went to fight in Gaul, leaving Deva with fewer soldiers. They probably had many losses before returning to Britain.

After some battles in the early 3rd century, the fortress at Deva was rebuilt again. This time, an enormous amount of stone was used. By the 4th century, the size of the legion, and thus the number of soldiers at Deva, might have become smaller, similar to other Roman forces.

The end of Roman rule

Most of the main buildings in the fortress were still kept up in the late 4th century, and the barracks were still used. After 383 AD, soldiers at Chester might have been taken away by Magnus Maximus when he went to Gaul. A document from around 395 AD, called the Notitia Dignitatum, does not list any army units at Deva. This suggests the fortress was no longer used by the military. If it was still used, this would have ended by 410 AD. This is when the Romans officially left Britain, and the Emperor Honorius told the cities of Britain to defend themselves. The local people probably kept using the fortress walls for protection against raiders.

Life in Chester continued, though on a smaller scale, after the Roman legions left. Buildings would have fallen apart, but some large structures lasted for a while. The town likely remained an important center for the area. When the Anglo-Saxons arrived, the settlement became known as Legacaestir, which means "City of the Legions" in Old English. In 907 AD, when Chester became an Anglo-Saxon town, the Roman fortress walls were repaired and used as part of the new defenses. Many Roman stones were reused in later buildings.

Discovering the past

In the 14th century, a monk named Ranulf Higden described some Roman remains in Chester, like sewers and tombstones. People became more interested in these remains in the 17th and 18th centuries. Discoveries included an altar to Jupiter Tanarus, a Roman version of the Celtic god Taranis. In 1725, William Stukeley recorded the Roman arches of the east gate, which were later taken down in 1768. More discoveries happened by accident, like parts of the Roman bath complex that were destroyed by new buildings.

The Chester Archaeological Society was started in 1849. They collected Roman artifacts and dug up sites when they could. The Grosvenor Museum opened in 1886 to show these collections to the public. The society kept working in Chester, recording information about the fortress and its surrounding town, often as new construction destroyed old sites. Between 1962 and 1999, about 50 excavations were done, revealing new information about Deva Victrix. More recently, between 2007 and 2009, digs happened at the amphitheatre.

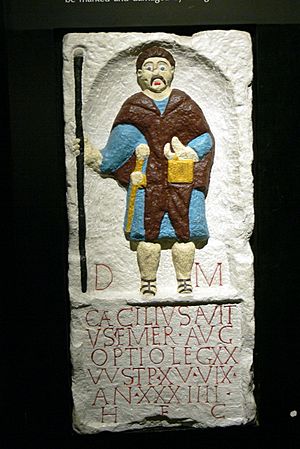

The Civilian Town

A town for civilians, called a canabae legionis, slowly grew outside the fortress walls. It probably started with traders who became rich by selling things to the soldiers. This town was managed by an elected council, not by the army. Many retired soldiers settled in the canabae legionis, making it a place for veterans. Cemeteries were located along the roads leading out of the town. The Grosvenor Museum has over 150 Roman tombstones, the largest collection from one site in Britain. Most of these were used to repair the north wall in the 4th century.

The town spread around the fortress to the east, south, and west. Shops lined the roads for about 300 meters (980 feet) beyond the fortress walls. To the east was the army's parade ground. Civilian baths were built to the west, and to the south was a mansio, a large guesthouse for government officials traveling through. The buildings in the canabae legionis were first made of timber, but in the early 2nd century, they started to be rebuilt in stone. The town grew throughout the 2nd and 3rd centuries as more people moved there. After the army left, the civilian town continued to exist and eventually became the city of Chester.

Some historians believe that after the Roman legions left in 410 AD, southern Britain kept a Roman way of life. They might have even used a type of Latin called British Latin for their culture. There's a chance this Latin was spoken in the Chester area until the late 7th century, as shown by old pottery and other Roman-British items found at Deva Victrix.

The Roman Quarry

The Roman fortress of Deva was built using local sandstone. This stone came from a quarry across the river, south of the fortress. You can still see traces of this quarry in Handbridge. In the 2nd century, a shrine to the Roman goddess Minerva was carved into the quarry rock. This was probably done by the quarry workers for protection. Even though it's very old and worn, you can still see Minerva holding a spear and a shield, with an owl on her left shoulder, which stands for wisdom. There's also a carving of an altar where people left offerings. This Minerva shrine is the only Roman shrine carved into rock that is still in its original place in Britain. It is a very important historic site.

Roman Baths

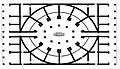

Deva Victrix had a huge bath complex for the soldiers. These baths, called thermae, were used for staying clean and for relaxing. They were located near the south gate and measured about 82.6 meters (271 feet) by 85.5 meters (280 feet). They were finished around the end of Emperor Vespasian's rule. The complex was built with concrete and covered with stone. The walls were 1.2 meters (4 feet) thick, and the arched buildings were as tall as 16.1 meters (53 feet).

The bath complex had many rooms: an entrance room, an exercise hall, a sweating room, a cold room with a cold pool, a warm room, and a hot room with a hot plunge bath. There was also an outdoor exercise yard. The baths had mosaic floors and were heated by a hypocaust system. This was an under-floor heating system connected to three furnaces. These furnaces needed several tons of wood every day!

The baths would have been open 24 hours a day, using about 850,000 liters (187,000 imperial gallons) of water daily. The water came from the springs in Boughton through underground lead pipes connected to the main aqueduct near the east gate. The water was stored in large tanks before flowing through the complex.

A big part of the baths was destroyed by building work in 1863 and again in 1963. Sandstone columns from the exercise hall, which were 0.75 meters (2.5 feet) wide, can still be seen in the "Roman Gardens" off Pepper Street. These columns were originally 5.9 meters (19 feet) tall. A section of the under-floor heating system (hypocaust) is still in place and can be seen in the cellar of 39 Bridge Street.

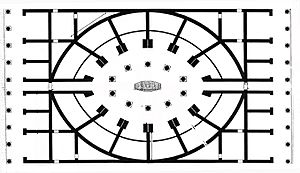

The Amphitheatre

The amphitheatre was found in 1929. The Chester Archaeological Society, with help from the Prime Minister at the time, saved it from being covered by a new road. Digs have shown that Deva's amphitheatre was built in two stages. The first one was made of timber soon after the fortress. It measured 75 by 67 meters (246 by 220 feet). There's no sign it was repaired, and its foundations were only 0.6 meters (2 feet) deep, so it might have been a temporary structure.

During the Flavian period, the amphitheatre was rebuilt with stone. This second version was larger, measuring 95.7 by 87.2 meters (314 by 286 feet). Only the seating area was made bigger, not the central arena. Recent excavations suggest it had two levels of seating and could hold between 8,000 and 10,000 people. Its large size shows that Deva had a big civilian population and wealthy citizens. This second stone amphitheatre is the largest military amphitheatre known in Britain. It is now a protected ancient monument.

The amphitheatre was used for many things. Since it was near the fortress, it was a place for soldiers to train with weapons. It also hosted exciting shows with acrobats, wrestlers, and professional gladiators. The walls of the amphitheatre were 0.9 meters (3 feet) thick and might have been as tall as 12 meters (39 feet).

A piece of a slate carving showing a retiarius, a type of gladiator who fought with a net, was found in 1738. It probably came from a gladiator's tomb. Other finds included a small bronze statue of a gladiator, parts of a Roman bowl showing gladiatorial fights, and part of a gladius (sword) handle. Much of the stone from the amphitheatre was reused to build St John's Church and the monastery of St Mary.

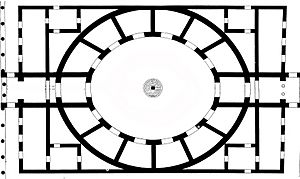

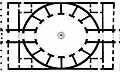

The Elliptical Building

In 1939, some paving and the walls of two unusual oval-shaped buildings were discovered, one built on top of the other. These "elliptical" buildings were found behind Chester's market hall. No similar buildings have been found in other Roman army fortresses. They were located near the center of the fortress and had their own bath buildings and storage rooms around them. Having a second bath building was unusual, as most fortresses only had one set of baths.

Construction on the site began around 77 AD. This was confirmed by a lead pipe that supplied water to a central fountain, which had the name of Emperor Vespasian stamped on it. The first building was very grand, with concrete foundations and finely cut stonework. It was probably the most impressive building in the whole fortress. It wasn't perfectly oval, but made of two curved sections that met. This makes it unique in the Roman Empire. We don't know its exact purpose. There were no seats inside, so it wasn't a theater. Archaeologists guess that the twelve curved spaces might have held statues of the gods, making it a temple dedicated to the twelve main Roman gods. Another idea is that the oval shape represented the known Roman world, but there's no proof for this.

The finished building was 52.4 meters (172 feet) by 31.45 meters (103 feet). It had an oval courtyard with a water feature in the middle, measuring 14 by 9 meters (46 by 30 feet). This courtyard was surrounded by 12 wedge-shaped rooms. Traces of the concrete foundation for the water feature and its lead pipes have been found. The 12 rooms around the courtyard had large arched entrances, 4 meters (13 feet) wide and at least 5.5 meters (18 feet) high. It's not certain if the first building was ever fully completed, but it was definitely destroyed by the 90s AD. After that, the site was used as the fortress's rubbish dump for many decades.

The second oval building was built on top of the foundations of the first. Even though the builders knew the exact layout of the old building, they changed the design slightly. While it looks very similar to the first, it used different curved sections to create a slightly wider shape. The second "elliptical" building wasn't built until about 220 AD. This was confirmed by a coin of Emperor Elagabalus found under one of the pavement slabs. It's thought that this second building might have lasted until the end of Roman rule in Britain.

Was Deva Victrix a Capital?

The unusual oval building is just one of several ways the fortress at Chester was different from other Roman fortresses in Britain. Deva was 20% larger, about 5 hectares (12 acres), than the fortresses at Eboracum (York) and Isca Augusta (Caerleon). Also, the stone walls at Chester were built without mortar, using large sandstone blocks. This required more skill and effort than the methods used for other fortresses. This type of building was usually saved for very important structures like temples or city walls, not just regular town walls.

The presence of these unique buildings in the heart of the fortress, which explains why Deva was 4 hectares (10 acres) larger than other fortresses, suggests that their construction was specifically ordered by the provincial governor. The governor of Roman Britain when construction first started was Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Lead pipes found in the oval building have his name on them, which is the only evidence in Britain of a building directly controlled by him. These differences suggest that Deva might have been Agricola's main administrative center – almost like the capital of Britannia. This idea was explored in a TV show called Timewatch.

Another reason why Deva Victrix might have been a provincial capital is its port. From Deva, it was possible to reach Ireland (Hibernia), a land that Agricola had plans to conquer. Also, the Flavian dynasty (the emperors at that time) wanted to expand the empire. Deva was closer to the front lines, making it easier and quicker to manage the army. Historian Vittorio Di Martino also believes that Agricola might have chosen Deva Victrix as a possible future capital because it was almost in the center of the British Isles, being roughly the same distance from the western shores of Ireland, the eastern lands of Britain, and the English Channel.

However, despite any plans for Deva, Londinium (modern-day London) became the capital of Britannia. This happened because the empire's policy changed from expanding to focusing on keeping what they already had. Londinium was the main economic and trading center.

Images for kids

-

A moulded antefix roof tile showing the badge and standard of Legion XX, from Holt, in north Wales

-

Foundations of the Roman south-east corner tower, one of the 22 towers built by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix

-

A Roman tombstone depicting Caecilius Avitus, an optio in the Legio XX Valeria Victrix

See also

In Spanish: Deva Victrix para niños

In Spanish: Deva Victrix para niños