Charles Booth (social reformer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Booth

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 30 March 1840 Liverpool, Lancashire, England

|

| Died | 23 November 1916 (aged 76) Thringstone, Leicestershire, England

|

| Resting place | St Andrew's, Thringstone |

| Occupation | Shipowner and social reformer |

|

Notable work

|

Life and Labour of the People in London |

| Spouse(s) | Mary née Macaulay |

| Awards | Guy Medal |

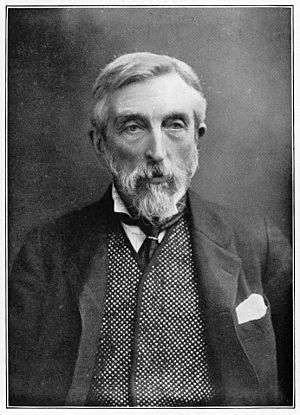

Charles James Booth (born March 30, 1840 – died November 23, 1916) was an important British shipowner and social researcher. He is famous for his studies on how working-class people lived in London in the late 1800s. His work helped change how people thought about poverty.

Booth was interested in the ideas of Auguste Comte, who started the study of sociology. Comte believed that scientists and business leaders would guide society in the future. Booth's research, along with that of Seebohm Rowntree, had a big impact on government policy in the early 1900s. It helped create Old Age Pensions and free school meals for children from poor families. His studies also showed how things like religion and education affected poverty.

Booth is best known for his large book series, Life and Labour of the People in London (1902). This book shared all the facts and figures he collected about poverty in London. It showed that many people were either poor or very close to being poor. Booth's work also helped change social attitudes from the Victorian Age into the 20th century. Because of his detailed studies, many people see Charles Booth as one of the first important figures in social administration. His work is still very important for understanding social policy.

Charles Booth: Helping Understand Poverty

Early Life and Family

Charles Booth was born in Liverpool, Lancashire, England, on March 30, 1840. His father was a rich shipowner and corn merchant. The family was also part of the Unitarian church. Charles went to the Royal Institution School in Liverpool. At 16, he started working in his family's business.

In 1862, he joined his brother, Alfred Booth, in the leather trade. Together, they started a very successful shipping line. Charles stayed involved with this business until he retired in 1912.

On April 19, 1871, Charles Booth married Mary Macaulay. They moved to London. Mary was the niece of the famous historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. She was also a cousin of Beatrice Webb, a writer and social reformer. Mary was known for being smart and well-educated. She also advised Charles on his business and helped a lot with his big study of London life. Charles and Mary Booth had seven children: three sons and four daughters.

His Business Career

When Charles's father died in 1860, Charles took over the family business. He and his older brother, Alfred, started Alfred Booth and Company. They opened offices in Liverpool and New York City. They used £20,000 they had inherited to start this new company.

After learning about shipping, Booth convinced his brother and sister to invest in steamships. They started a shipping service to Brazil. In 1866, Charles and Alfred Booth officially launched the Booth Steamship Company. Charles himself went on the first trip to Brazil in February 1866. He also helped build a harbor in Manaus, Brazil. This harbor helped ships deal with changing water levels. Booth called this harbor his "monument" to shipping. He wrote letters to his wife about business challenges, like managing staff and moving factories. These letters showed his early ideas about business ethics.

Studying Poverty in London

Booth became very interested in studying poverty. In 1886, he started his huge survey of life and work in London. This study made him famous and is seen as the start of how poverty was studied in Britain. Booth thought the existing information about poverty was not good enough. He looked at census records and found them incomplete. He was later asked to join a government committee in 1891 to suggest ways to improve the census.

His survey was so big that the results were published over many years. It took more than 15 years for all 17 volumes to be released. His work on this study made him want to campaign for old-age pensions. He also pushed for changes to make work more steady for people.

Booth disagreed with H. M. Hyndman, a socialist leader, who claimed that 25% of Londoners lived in extreme poverty. Booth started his survey in Tower Hamlets. He hired many researchers, including his cousin Beatrice Potter (Beatrice Webb) and economist Clara Collet, to help him. This research showed that 35% of people in the East End of London were living in extreme poverty. This was even higher than Hyndman's number. This first part of his work was published in 1889 as Life and Labour of the People. A second book, Labour and Life of the People, covering the rest of London, came out in 1891.

Booth also made the idea of a "poverty line" popular. This idea came from the London School Board. Booth set this line at 10 to 20 shillings a week. He believed this was the least amount of money a family of 4 or 5 needed to survive.

After the first two books, Booth expanded his research. He continued to manage his successful shipping business, which paid for his charity work. The results of this bigger study were published as a second edition of his original work. It was called Life and Labour of the People in London and came out in nine volumes between 1892 and 1897. A third edition, with 17 volumes, was published in 1902–03.

Booth used his work to argue for Old Age Pensions. He called this "limited socialism." Booth thought such changes would help prevent a socialist revolution in Britain. He was not a socialist himself, but he cared about working-class people. As part of his studies, he even stayed with working-class families and wrote down his experiences.

The London School of Economics has his work online. It includes his private notebooks, which show how he worked and how he felt about his discoveries.

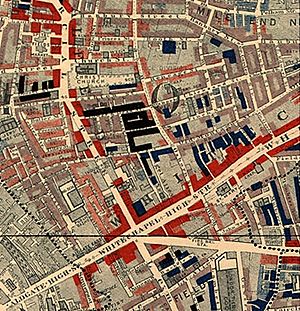

Mapping Poverty

From 1886 to 1903, Charles Booth created special maps to show the living conditions of London's poorest people. These maps were based on what he observed about people's lifestyles. They looked at things like food, clothing, shelter, and how much people lacked compared to others.

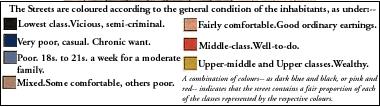

Booth and his team visited every street in London. They decided on a "class" for each household, from A to H. Classes A to D meant the household was in need, while E to H meant they were comfortable. Booth's maps used different colors for each street to show the level of poverty or comfort.

The goal was to show Victorian society the big problem of poverty. Many people who looked at the maps noticed that there was more poverty south of the River Thames than in the East End Slums. The colors on the maps were also important. Areas with a lot of poverty were shown in dark colors, while comfortable areas were bright, like pink, blue, and red. The maps tried to show that poverty was a problem that could be managed and solved.

What He Learned About Religion

By 1897, Charles Booth had spent a lot of money and ten years studying the poor in London. He then asked himself: "What role can religion play in these conditions?" This question led to six more years of research. He and his team interviewed 1,800 religious and non-religious leaders in London.

They created seven books called the "Religious Influences" series. This series showed that there was less disagreement about "charity organization" in the late 1800s. Booth and his team found that church leaders, women, and working people liked the idea of carefully giving out charity. Church leaders were in charge of deciding who needed help. Many believed that giving too much would lead to problems.

Booth's team supported charity organizations. However, they also thought that giving very little, or nothing, could help people build their character. The interviews focused more on the money churches gave to the poor and jobless, rather than the actual religious influence. Booth thought that some of the charity given by churches was being wasted. So, at the end of his survey, Booth suggested that church relief work should stop. He believed that officials should be responsible for helping those who truly needed it.

How He Studied Poverty

For his poverty studies, Booth divided working people into eight groups, from the poorest (A) to the best off (H). These groups described their money situation and also had a moral side.

Professor Paul Spicker noted that Booth's studies are often misunderstood. While his work is often grouped with Seebohm Rowntree's, their methods were different. Booth's definition of poverty was based on how people lived, not just on a fixed income level. He didn't try to say exactly how much money someone needed to survive. His "poverty line" was a way to show poverty, not a strict definition. He wanted to describe the conditions in which people were poor. To do this, he used many different ways to collect information, both facts and stories, to give a full picture of poverty.

Criticisms of His Work

Booth's survey has received some criticism for how he collected information. He used school board visitors, who made sure children went to school, to gather details about families. However, he then guessed about families without school-aged children, which might not have been accurate. Also, his "definitions" of poverty levels were general descriptions, not exact rules. Even though his 17 books were full of interesting details, they mostly described things rather than explaining why they happened.

Booth's London Poverty Maps also received criticism. The dark colors used for poor areas made them look like a disease. This created a negative feeling about those communities. However, the way the map was scaled made it seem like the problem could be fixed.

Booth is often compared to Seebohm Rowntree because they both studied poverty. While Rowntree's work was inspired by Booth's, many writers focus on Rowntree's work because he clearly defined a "subsistence" level of poverty (the minimum needed to survive). Both Booth and Rowntree studied society scientifically. However, they had different methods. Booth grouped people by where their money came from, while Rowntree grouped them by their social class and economic relationships.

His Impact and Legacy

Life and Labour of the People in London is considered one of the first important books in British sociology. It used both statistical methods and observational methods. It influenced many other social reformers and sociologists.

Booth's poverty maps showed that poverty is linked to specific places and environments. Before his maps, environmental reasons for poverty were mostly of interest to health experts. Booth brought these environmental issues into the study of society.

His work also inspired other academics, like Hubert Llewellyn-Smith, who did a similar survey in London later. Booth's work also influenced Seebohm Rowntree, Beatrice Webb, and Helen Bosanquet.

Important Awards

The Royal Statistical Society recognized the importance of Booth's work in social statistics. In 1892, he became their President. He also received their first Guy Medal in Gold. In 1899, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, a very high honor for scientists.

Politics and Later Life

Booth was involved in politics early on. He campaigned for the Liberal Party in the 1865 General Election, but he didn't win. After the Conservative Party won local elections in 1866, he became less interested in active politics. He decided he could do more good by leading social studies instead of being a politician.

Booth was offered a high honor by Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone to become a peer (a lord) and sit in the House of Lords, but he declined it. Booth also worked with Joseph Chamberlain's National Education League. This group studied work and education in Liverpool. They found that 25,000 children in Liverpool were neither in school nor working. In 1904, Booth became a member of the Privy Council, a group of advisors to the King or Queen.

Even though his ideas about poverty might seem progressive, Booth became more traditional in his views later in life. While some of his researchers, like Beatrice Webb, became socialists because of their studies, Booth was critical of the Liberal Government after they won the 1906 General Election. He felt they supported trade unions too much.

His Final Years

Booth bought the famous painting The Light of The World by William Holman Hunt. He gave it to St Paul's Cathedral in 1908.

In early 1912, Booth stepped down as chairman of Alfred Booth and Company. His nephew, Alfred Allen Booth, took over. However, in 1915, Charles willingly returned to work during World War I, even though he was showing signs of heart disease.

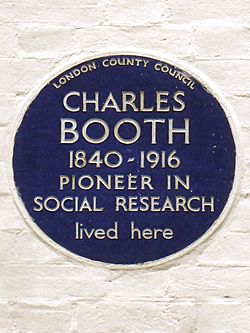

The Booth family moved to Grace Dieu Manor near Thringstone, Leicestershire, in 1886. This is where Charles retired. Before he died, he hosted many family gatherings to be with his friends, children, and grandchildren. He passed away on November 23, 1916, from a stroke. He was buried in Saint Andrew's churchyard. There is a memorial for him on Thringstone village green, and a blue plaque is on his house in South Kensington, London.

His Famous Books

- Life and Labour of the People, 1st ed., Vol. I. (1889).

- Labour and Life of the People, 1st ed., Vol II. (1891).

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 2nd ed., (1892–97); 9 vols.

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 3rd ed., (1902–03); 17 vols.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Booth para niños

In Spanish: Charles Booth para niños

- Booth baronets

- Alfred Booth and Company

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |