Charles Herbert Garvin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Herbert Garvin

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | October 27, 1890 |

| Died | July 17, 1968 (aged 77) |

| Education | Atlanta University Academy (1904–1908) Howard University (1908–1911) Howard University College of Medicine (1911–1915) |

| Occupation | Physician (urologist) Writer Professor |

| Employer | Freedmen's Hospital Howard University Lakeside Hospital Western Reserve University (1930–1937) |

| Title | |

| Spouse(s) | Rosalind West (m. 1920) |

| Children | Dr. Harry C. Garvin Charles Garvin |

| Parent(s) | Charles Edward Garvin Theresa De Corcey |

| Signature | |

Charles Herbert Garvin (October 27, 1890 – July 17, 1968) was an important African-American doctor, writer, and teacher in Cleveland, Ohio. He wrote many articles for the Journal of the National Medical Association. These articles covered topics like tuberculosis in African-American communities and the history of the black movement.

Garvin served as a captain in World War I. He was part of the 92nd Division, which was a unit for African-American soldiers because of segregation laws at the time. He worked as a surgeon in France with the 367th Infantry.

After the war, Garvin held many important roles. He was a chief instructor at Western Reserve University and an editor for the Journal of the National Medical Association. He also became the president of the Cleveland branch of the National Negro Medical Association. Garvin was a close friend of W.E.B. Du Bois, a famous civil rights leader.

Contents

Growing Up and School

Charles Garvin was born in Jacksonville, Florida. His parents were Charles Edward Garvin and Theresa De Corcey. We don't know much about his early life, except for his school records. He went to public schools in Jacksonville before attending Atlanta University Academy from 1904 to 1908.

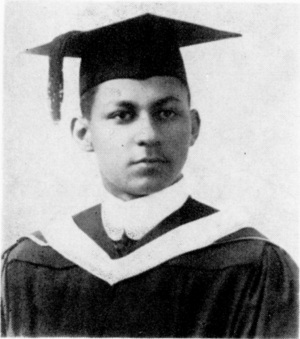

In 1908, Garvin started college at Howard University in Washington D.C.. He liked the lively African-American community there. So, he decided to stay and attend Howard University College of Medicine in 1911. He finished medical school in 1915, and the local newspaper celebrated his achievement.

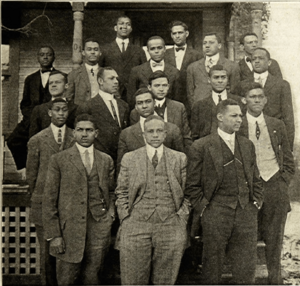

Garvin was very involved in his community during his time at Howard. He became an active member of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. This fraternity was started in 1906 and has had many successful members, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Jesse Owens. From 1911 to 1912, Garvin was the General Secretary and Executive Director of Alpha Phi Alpha. In 1912, he was elected as the fourth president of the fraternity. He served two terms, from 1912 to 1914.

As president, Garvin wrote a guide for the fraternity called "Esprit De Fraternite." He wrote that members should focus on what they can do for the fraternity, not just what they can get from it. He also listed duties for members, such as paying dues, doing well in school, joining college activities, and keeping high moral standards. Garvin was the first president to serve two terms. He helped the fraternity get its own house and worked to improve its image for the future. He also helped make the fraternity a national organization under U.S. laws.

During his second term, Garvin worked closely with the NAACP. He even wrote an article for their magazine, The Crisis, about Alpha Phi Alpha. In the article, he said the fraternity was founded to bring together "the best type of men." He believed that black Greek-letter fraternities were important for connecting black college men.

In 1913, the fraternity decided to start its own magazine called The Sphinx. After his presidency, Garvin continued to be involved. He was appointed the fraternity's first historian. This interest in recording the history of African Americans continued throughout his life. He remained active in Alpha Phi Alpha until he passed away in 1968.

After medical school, Garvin started an internship at Freedmen's Hospital.

Military Service in World War I

In 1917, the United States joined World War I. Many African Americans wanted to join the military, but they often faced rejection. The U.S. Army had only four black regiments, and many commanders did not want black and white soldiers to serve together. Also, some leaders doubted that black soldiers could fight well in Europe. However, a training school for African-American officers was opened at Fort Des Moines after many black volunteers came forward.

When Dr. Garvin joined the military as a doctor, he was immediately made a first lieutenant in the Army Medical Reserve Corps. Like other African-American recruits, he went to Fort Des Moines for medical training. After his training, he became a battalion surgeon for the 1st Battalion, 367th Infantry. In September 1918, Garvin was promoted to commanding officer of the 368th Ambulance Company. Besides being a surgeon, he was also in charge of making sure the company had all its supplies and could move injured soldiers efficiently.

Before going to France, Garvin was promoted to Captain. In France, Captain Garvin had a lot of work. His unit, the 92nd Division, was sent to the trenches to help French troops who had been fighting the Germans for months. Captain Garvin spent much of his time treating soldiers for illnesses like influenza and gas inhalation. Many African-American soldiers were assigned to dangerous jobs like digging trenches and building roads. Captain Garvin cared for those who were badly injured from this work. The Germans often used gas shells, which filled hospitals with soldiers suffering from lung problems.

Captain Garvin expected his soldiers to perform well. He disagreed with statements from General Pershing that black soldiers were not doing well in the war. Garvin wanted his soldiers to prove Pershing wrong, and he often wrote about this in African-American newspapers.

When the 92nd Division arrived in France, they were moved to the St. Dre Sector. They replaced a white U.S. Army division. Soon after, the 5th Division captured the village of Frapelle. Garvin's unit was then sent into the harsh trenches, where Germans were constantly attacking. In mid-September, Frapelle faced heavy German bombing. Captain Garvin was very busy treating the wounded. At one point, the Germans learned that the 92nd Division was made up entirely of African Americans. The Germans then changed their tactics. They threw shells into the trenches that contained propaganda written in English. This propaganda tried to convince the black soldiers to stop fighting.

However, Captain Garvin and his fellow soldiers did not fall for the German tricks. They continued fighting bravely. The fighting continued, but French anti-aircraft guns helped stop the German air attacks. The division then moved to Ste. Menehold. In October, the 92nd Division became a reserve unit for the Mseu-Argonne campaign. In November, Captain Garvin and his unit faced another strong German attack in Metz.

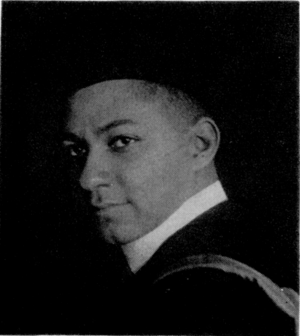

Captain Garvin was honorably discharged from the military in 1919. His war experiences stayed with him. He later wrote several articles about the contributions of African Americans during World War I. His most famous work on this topic was "The Negro in the Special Services of the U. S. Army: Medical Corps, Dental Corps and Nurses Corps" (1943), published in The Journal of Negro Education.

Medical Career and Community Leadership

After the war, Dr. Garvin returned to Cleveland and opened his own medical practice. In 1920, he began teaching at Western Reserve University, where he stayed until 1937. He also worked at Lakeside Hospital as an assistant surgeon for urinary diseases. This made him the first African-American doctor to be appointed to a Cleveland hospital. This was very important because a survey in 1920 showed that only 19 doctors in Cleveland were allowed to apply for hospital staff positions, and only Garvin was given an appointment. However, he still faced discrimination. His duties were limited to outpatient care, and he could not admit patients on his own.

Garvin encouraged his colleagues to study illnesses that affected African-American communities more, like tuberculosis. He disagreed with the idea that these diseases were due to racial differences. He wanted research to prove that environmental factors, like poor living conditions, were the real cause. He believed that black doctors should lead this research.

Dr. Garvin also attended clinics led by Dr. George W. Criles. Once, Dr. Criles found a tumor during a surgery and didn't know what it was. Dr. Garvin correctly identified it as a desmoid tumor. This incident was reported in the news and helped build Garvin's reputation, leading to his position at Lakeside Hospital.

Wanting his family to have the same opportunities as white families, Garvin moved into a white neighborhood and built his home at 11114 Wade Park Avenue. Many people protested his move. Crowds gathered, and graffiti was sprayed on his property. One morning, the family found "KKK" written on their windows. The police then posted a guard around their home. On January 31, 1926, someone threw a firebomb at the house, but it caused little damage. This event made national headlines, and the Garvin family received police protection. The NAACP also spoke out, asking the Cleveland community to support the Garvin family. Three weeks later, another bomb was thrown, but it did not explode. Garvin threw it back out the window, and no one was hurt. Despite these threats, Garvin fixed up the house and moved in with his family a few months later. His sister told the press that he had made a home and would stay there.

The Garvins became strong supporters of African-American independence and were seen as community leaders. Garvin worked to unite black leaders and emphasized the need for a strong, unified black society. He promoted racial pride and black solidarity. He was an active member of the NAACP and the National Urban League, helping with many cases of housing discrimination.

Garvin also helped start the Dunbar Life Insurance Company and Quincy Savings and Loan. He was a trustee for the Karamu House in Cleveland, a center for arts and education.

In 1925, Dr. Garvin helped create the Cleveland Medical Reading Club. This club helped African-American doctors stay updated on medical advances, as many white hospitals still followed Jim Crow laws that segregated facilities.

His interest in medicine went beyond his practice. He researched and wrote about the history of Africans and African Americans in medicine. He completed a book on this topic that was never published, but it can be found at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Garvin was part of a big effort to create an all-black hospital in Cleveland. This idea started in the early 1920s but failed due to lack of money. Between 1926 and 1927, black doctors in Cleveland tried again. This time, they were more organized and successful. In 1926, the Cleveland Hospital Association supported the idea, and it was renamed the Mercy Hospital Association. Garvin was one of its main leaders.

There is some discussion about whether Dr. Garvin was an "integrationist" (someone who wanted black and white people to mix) or a "separatist" (someone who wanted black people to have their own institutions). He strongly supported groups that wanted integration, fought for the right to live in a white neighborhood, and was the only black doctor in an all-white hospital. However, like his friend Dr. DuBois, Garvin also strongly supported creating all-black institutions. He was a leading supporter of forming an all-black hospital in Cleveland. Garvin believed that integration offered good opportunities, but he also felt the racism and discrimination from his white colleagues. He shared his uncomfortable experiences at Lakeside Hospital in a speech.

According to public records from 1949, Dr. Garvin was a member of the Cleveland Public Library Board. He worked hard to provide more resources for researchers and writers. In 1963, Howard University gave Dr. Garvin the Warfield Award for his work and contributions to the school's executive board.

Garvin wrote often for the Journal of the National Medical Association, publishing 26 papers. He also served as the journal's editor for most of his career.

Family Life

In 1921, Dr. Garvin married Rosalind West, who was from Charlottesville, Virginia. They met at Howard University, where Rosalind studied education. They had two sons: Charles West Garvin (born June 29, 1921) and Henry Clark Garvin (born June 26, 1928). His younger son, Henry, followed in his father's footsteps and became a doctor. He graduated from Amherst College and Western Reserve Medical School. In his later years, Garvin shared a medical practice with his son.

Later Years and Legacy

Dr. Garvin passed away in 1968. He was survived by his son, Harry, and his wife. The Journal of the National Medical Association dedicated a part of their 1969 publication to his life and achievements. In the years after his death, Dr. Garvin was often mentioned in the historical section of the African-American magazine Jet.

A collection of Dr. Garvin's writings, letters, and other works are now kept at the Western Reserve Historical Society. Garvin's son continued his legacy by succeeding him in the Cleveland Reading Club.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |