Charles Inglis (engineer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Inglis

|

|

|---|---|

1926 portrait by Douglas Gordon Shields

|

|

| Born |

Charles Edward Inglis

31 July 1875 Worcester, Worcestershire, England

|

| Died | 19 April 1952 (aged 76) |

| Education | Cheltenham College King's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse(s) | Eleanor Moffatt |

| Children | Two daughters |

| Parent(s) | Dr. Alexander Inglis Florence Feeney Inglis |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil, Mechanical, Structural |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers (president), Institution of Mechanical Engineers (honorary member), Institution of Naval Architects (council member), Institution of Structural Engineers (council member), Institution of Waterworks Engineers (council member), Royal Society (fellow) |

| Significant design | Inglis Bridge |

| Awards | Telford Medal Charles Parsons medal Fellow of the Royal Society |

Sir Charles Edward Inglis (born July 31, 1875 – died April 19, 1952) was a famous British civil engineer. He was the son of a doctor. Charles Inglis went to Cheltenham College and then to King's College, Cambridge. He later became a professor there.

Inglis worked for an engineering company for two years. After that, he returned to King's College as a teacher. He studied how vibrations affect structures. He also looked at how small flaws can weaken steel.

During the First World War, Inglis served in the Royal Engineers. He invented the Inglis Bridge, which was a steel bridge that could be used again and again. This bridge was an early version of the more famous Bailey bridge used in the Second World War. In 1916, he was put in charge of designing and supplying bridges for the army. He also helped create temporary bridges that tanks could use.

After the war, Inglis left the army in 1919. He was given an award called the Officer of the Order of the British Empire. He went back to Cambridge University as a professor. He became the head of the Cambridge University Engineering Department. Under his leadership, this department grew to be one of the best engineering schools in the world. Inglis retired from the department in 1943.

Inglis was part of many important engineering groups. He was even the president of the Institution of Civil Engineers from 1941 to 1942. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Society, which is a very high honor for scientists. He helped investigate the crash of the airship R101. In 1945, he was made a knight. In his later years, he wrote a textbook about applied mechanics. Many people called him the greatest engineering teacher of his time. A building at Cambridge University is named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Charles Inglis was born on July 31, 1875. His father, Dr. Alexander Inglis, was a doctor in Worcester, England. Charles's mother passed away shortly after he was born.

His family later moved to Cheltenham. Charles went to Cheltenham College from 1889 to 1894. In his last year, he was the head boy. He also won a scholarship to study mathematics at King's College, Cambridge. He earned his first degree in 1897. He then studied Mechanical Sciences and achieved top honors.

Charles was also a good athlete. He enjoyed running, walking, climbing, and sailing. He almost earned a "blue" for long-distance running at Cambridge. This award is given to top university athletes.

After finishing university, Inglis became an apprentice at an engineering company. He worked as a draughtsman (someone who draws plans). He then helped supervise the building of thirteen bridges for a railway extension in London. During this time, he started studying how vibrations affect materials, especially bridges. This became a lifelong interest for him.

Starting His Academic Career

In 1901, Inglis became a fellow of King's College. He wrote a paper about how to balance engines. This topic was becoming very important as engines got faster. In the same year, he earned his Master of Arts degree. He also won an award for his paper on how to solve mechanical problems using geometry.

Inglis left his job at the engineering company. He returned to King's College to work with Professor James Alfred Ewing. Professor Ewing later left to work for the British Navy. Inglis stayed and worked with the new professor, Bertram Hopkinson. They studied the effects of vibration together.

In 1908, Inglis became a lecturer in mechanical engineering. He taught many subjects, including how structures work and how to design steel and concrete. He once said that if he wanted to learn more about a topic, he would volunteer to teach a course on it!

From 1911, Inglis also worked in water engineering. He was on the board of the Cambridge Water Company. He even became its chairman from 1928 to 1952.

Inglis also researched why metal plates in ship hulls would crack. He noticed that rivet holes often became stretched into an oval shape near cracks. This led him to study how stress gets much stronger at the edges of a flaw. In 1913, he published a paper about his ideas. This paper is considered one of his most important contributions to engineering. It was one of the first serious modern studies on how materials break.

In 1901, Inglis married Eleanor Moffat. They had two daughters.

Military Service and the Inglis Bridge

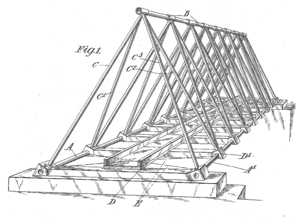

Inglis was part of the Cambridge University Officer Training Corps. He noticed that his engineering unit often had nothing to do during army exercises. So, he designed a steel bridge that could be put together and taken apart quickly. This bridge could be reused.

When the First World War started in 1914, Inglis joined the British Army. The army was very interested in his bridge design. It was approved for use. The Inglis Bridge was designed so that soldiers could move all its parts by hand. It could also be built with few tools in a short time. For example, 40 soldiers could build a 60-foot bridge in 12 hours.

The bridge was made of 15-foot sections of steel tubes. It could span up to 90 feet. The design was improved three times. The Mark II version used tubes of the same length, making it simpler. The Mark III used stronger steel, which allowed it to carry heavier loads. Inglis also developed a similar observation tower during the war.

In 1916, Inglis was put in charge of bridge design for the War Office. He pushed for more use of strong girder bridges in the army. He showed that even heavy bridge parts could be put together quickly in the field. This led to more use of bridges like the Inglis Bridge for tanks. He was promoted to captain and then major. He also worked with Giffard Le Quesne Martel to create some of the first tank-laying bridges. Inglis left the army in 1919.

Back to Cambridge University

Inglis returned to Cambridge in 1918. He became a professor and head of the Cambridge University Engineering Department. He made the department the largest at the university. It became one of the best engineering schools in the world. He expanded the department to meet the demand for engineers after the war. He also moved it to a new, larger location.

Inglis taught many students who became very famous engineers. These included Sir Frank Whittle, who developed the jet engine, and Sir Morien Morgan, known as the "Father of Concorde". Inglis wanted to give his students a broad education in engineering. He didn't want them to specialize too early.

Inglis worked closely with industries. He helped create a professorship in aeronautical engineering (airplane design). He also arranged for army officers to study engineering at the university.

From 1923, Inglis studied how vibrations affected railway bridges. He worked on a government committee that looked into this. Inglis created a theory to accurately measure vibrations caused by trains. The committee's report in 1928 suggested that these forces should be included in bridge designs. He also showed that the way a train's suspension works affects bridge vibrations. This was the first time this was explained.

Inglis became a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) in 1923. He was very active in many professional groups. He also wrote many books and papers on engineering. In 1924, he received the ICE's Telford Medal for his work on bridge vibrations.

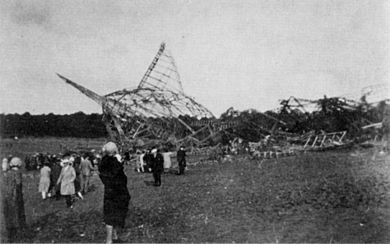

In 1930, Inglis was part of the investigation into the crash of the airship R101. In the same year, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He also helped the London, Midland and Scottish Railway with scientific research. He studied why railway carriages would shake violently. He also developed equipment to test how train tracks and wheels wear down.

Inglis published a book called A Mathematical Treatise on Vibrations in Railway Bridges in 1934. He also gave many lectures. He was president of the British Waterworks Association in 1935. He was also president of an international engineering conference in 1934.

Second World War and Later Life

Inglis was supposed to retire from the university in 1940. But he stayed for three more years. During the Second World War, there was new interest in his Inglis Bridge. The Mark III design was introduced in 1940. However, the Bailey bridge, introduced in 1941, largely replaced it. This was a bit disappointing for Inglis. Still, the Inglis Bridge was used in some areas because there weren't enough Bailey bridges.

Inglis became president of the ICE for 1941–42. He gave a famous speech about how engineers should be educated. He said that the most important part of education is the way of thinking that stays with you, even if you forget everything you were taught. He also gave other important lectures on vibrations.

After retiring as department head, Inglis was a Vice-Provost of King's College from 1943 to 1947. He was made a knight in 1945. In 1946, he led a committee that advised the government on modernizing railways.

Inglis kept working on his ideas about teaching engineering. He wrote that the math engineers need is practical, like a "tin-opener." He meant that engineers care more about solving problems than about fancy math. In 1951, he published a textbook called Applied Mechanics for Engineers.

His wife, Lady Eleanor Inglis, passed away in April 1952. Charles Inglis died eighteen days later. The Inglis Building at Cambridge University is named in his honor. He is remembered as one of the greatest engineering teachers of his time.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |