Charles R. Drew facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Richard Drew

|

|

|---|---|

Charles Richard Drew

|

|

| Born | June 3, 1904 Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Died | April 1, 1950 (aged 45) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Amherst College, McGill University, Columbia University |

| Known for | Blood banking, blood transfusions |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | General surgery |

| Institutions | Freedman's Hospital Morgan State University Montreal General Hospital Howard University |

| Doctoral advisor | John Beattie |

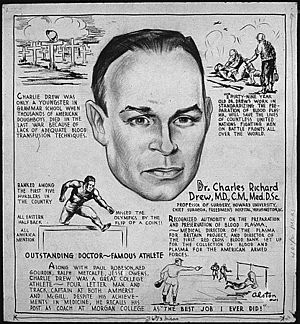

Charles Richard Drew (born June 3, 1904 – died April 1, 1950) was an American surgeon and medical researcher. He found better ways to store blood for blood transfusions. His ideas helped create large blood banks early in World War II. This saved many lives of soldiers and civilians.

Dr. Drew was a leading African American in medicine. He spoke out against racial segregation in blood donation. He believed it was wrong and had no scientific reason. He even resigned from the American Red Cross because they kept this policy.

Contents

Early Life and School

Charles Drew was born in 1904 in Washington, D.C.. His family was middle-class and African-American. His father, Richard, laid carpets. His mother, Nora Burrell, was a trained teacher. Charles and his siblings grew up in a mixed neighborhood called Foggy Bottom. He went to Dunbar High School and graduated in 1922.

Drew was a great athlete. He won a sports scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts. He graduated from Amherst in 1926. After college, he taught chemistry and biology at Morgan College. He was also the first athletic director and football coach there. He worked to save money for medical school.

He studied medicine at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He was an excellent student, ranking second in his class. He earned his medical degree in 1933.

Later, Drew did more advanced studies at Columbia University in New York City. He focused on how to keep blood fresh for longer. In 1940, he earned his Doctor of Science in Medicine degree. He was the first African American to achieve this.

Blood for Britain Project

In late 1940, before the U.S. joined World War II, Dr. Drew was asked to help. He was to set up a program to store and send blood. This project was called "Blood for Britain." Its goal was to send blood plasma to the United Kingdom. This plasma would help British soldiers and civilians.

Dr. Drew became the medical director of the project. He created "bloodmobiles." These were trucks with refrigerators to carry stored blood. This made it easier to transport blood and collect donations.

He set up a main place for blood collection. He made sure all blood plasma was tested. He also ensured only skilled people handled the blood. This prevented contamination. The "Blood for Britain" program worked well for five months. Almost 15,000 people donated blood. Over 5,500 vials of blood plasma were sent.

American Red Cross Blood Bank

Because of his great work, Dr. Drew became the director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank in February 1941. This blood bank was in charge of blood for the U.S. Army and Navy.

However, Dr. Drew strongly disagreed with a rule. The rule said that blood from African Americans had to be kept separate from blood from white people. This was called racial segregation. Dr. Drew knew there was no scientific reason for this. In 1942, he resigned from his positions. He did this to protest the unfair policy.

Later Career and Awards

In 1941, Dr. Drew became the first African-American surgeon to be an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. This was a big honor.

He continued his research and teaching career. He returned to Freedman's Hospital and Howard University. In 1944, he received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP. This award recognized his important work on blood projects. He also received honorary science degrees from Virginia State College in 1945 and Amherst in 1947.

Personal Life

In 1939, Dr. Drew married Minnie Lenore Robbins. She was a professor of home economics. They had three daughters and one son. His daughter, Charlene Drew Jarvis, later became a well-known leader in Washington, D.C.

Death

In 1950, Dr. Drew was driving to a medical clinic in Tuskegee, Alabama. He was with three other doctors. On April 1, around 8 a.m., he lost control of his car. The car crashed. The other doctors had minor injuries. Dr. Drew was badly hurt and trapped.

He was taken to Alamance General Hospital in Burlington, North Carolina. Sadly, he passed away a short time later. His funeral was held on April 5, 1950, in Washington, D.C..

Legacy

Dr. Charles Drew's work changed medicine forever. He made blood storage safe and efficient. This saved countless lives, especially during wartime. He also stood up for what was right, fighting against unfair racial policies.

Many places and institutions are named in his honor:

- In 1976, his home in Virginia became a National Historic Landmark.

- In 1981, the United States Postal Service put his image on a postage stamp.

- The Charles Richard Drew Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., is named after him.

- The USNS Charles Drew is a U.S. Navy ship.

- In 2002, he was listed as one of the "100 Greatest African Americans."

Many schools and health centers also carry his name:

- The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in California.

- Charles Drew Health Center in Omaha, Nebraska.

- Charles Drew Science Enrichment Laboratory at Michigan State University.

- Many K-12 schools across the country, like Charles R. Drew Middle School in Los Angeles.

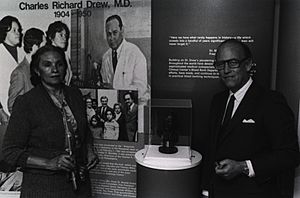

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Richard Drew para niños

In Spanish: Charles Richard Drew para niños