Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

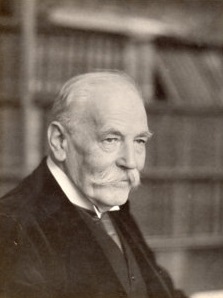

Sir Charles Hagberg Wright

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright

17 November 1862 |

| Died | 7 March 1940 (aged 77) |

| Alma mater | Royal Belfast Academical Institution Trinity College, Dublin |

| Occupation | Librarian |

Sir Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright (born November 17, 1862, in Middleton Tyas, Yorkshire – died March 7, 1940, in London) was a very important person at the London Library. He was its Secretary and Librarian from 1893 until he passed away. He helped the library grow a lot and created a detailed list of all its books. The Times newspaper called him the library's "guiding genius" because he was the main reason for its growth over 40 years. The London Library itself says Wright was "the real architect" of what it is today.

Wright was also a very public person. He often joined in important discussions about politics. He was interested in many things, from the history of how Africa was colonized to translating books by Leo Tolstoy. People saw him as someone who liked Russia and its culture. He was involved in Russian politics and helped Russian soldiers and thinkers during wartime.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Family

Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright was born in Yorkshire, England. His family had roots in both Ireland and Sweden. He was the third son of Reverend Charles Henry Hamilton Wright. His father was a church leader who worked in Belfast, Dublin, and Liverpool. He also helped run the Protestant Reformation Society. Charles's mother was the daughter of Nils Wilhelm Almroth, who was in charge of the Swedish Royal Mint in Stockholm. His brother, Almroth Wright, became a famous scientist who studied bacteria.

Charles was taught at home in Russia, France, and Germany. He also went to the Royal Belfast Academical Institution and Trinity College in Dublin. In 1890, he started working at the National Library of Ireland. For the next three years, he organized their books using the Dewey system, which is a way to sort books by topic. In 1893, he was chosen to be the Secretary and Librarian of the London Library.

Growing the London Library

The London Library got its own building in 1879. Between 1896 and 1898, the building was completely rebuilt. It became one of the first buildings in London to use a steel frame, which made it very strong. The library's unique look today, including its Main Hall and Reading Room, comes from Wright's time. The library has grown even more since then, with big expansions in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1990s.

The number of books at the library grew a lot under Wright. They bought many new books and also received donations from people. By 1913, the library had 250,000 books, and by 1928, it had 400,000. (It reached 500,000 books in 1950). When important book collections were going to be sold to buyers from other countries, like Sir Henry Clinton's library, Hagberg Wright spoke out. He wanted to keep these valuable books in England.

Wright focused on buying books about literature and social sciences. He especially liked books from British academic groups. Books about general science and natural history were not as common, and there were almost no books on medicine or technology. In 1920, the library bought the Allan collection. This was a group of books about Biblical studies and the Protestant Reformation, including some very old books called incunabula. Later, in the 1920s, Wright decided to get rid of some "minor 19th-century fiction" that wasn't very popular anymore. T. S. Eliot, a famous writer who later became the library's President, said that the library had "so many books which I might want, and so few of the books which I cannot imagine anyone wanting."

Creating the Library Catalogue

Before Wright, the library's list of books was just small additions to its first catalogue from 1842. This wasn't very helpful. So, Wright worked hard to create a proper, modern catalogue. The first version, put together by Wright and Christopher Purnell, was printed in 1903. A second, bigger version came out in 1913–14. It was 1626 pages long! More updates were printed in 1920 and 1929.

The catalogue was organized into six large books for people to use. There were also 38 even bigger books for the library staff to use every day. Wright also published a helpful Subject Index in 1909, 1923, and 1938. His catalogues became famous for being very careful and accurate. They were especially good at figuring out who wrote books that were published without a name or with a fake name. These catalogues became a standard guide for librarians in Britain and other countries. Wright's system is still the basis for the library's electronic database today.

Wright was made a knight on January 1, 1934. His biggest wish was to lead the London Library through its 100th birthday in 1941.

Public Work and Russian Connections

In 1901, Wright helped start the African Society. He wrote an article about the German colonization of Africa for their first magazine, the Journal of the African Society. When World War I began, Hagberg Wright signed a letter from British scholars to German professors. It said that Britain had to continue the war for "liberty and peace." During the war, he was a main helper for The War Library. This library was set up in 1914 to give books to British soldiers fighting, resting, in hospitals, and in prisoner of war camps. He also worked to create libraries for Russian prisoners in Germany.

Wright was known for liking Russia and its culture. He translated books by Leo Tolstoy, a famous Russian writer. Wright wrote that Tolstoy's greatness was sometimes hard to see because he was both a realist and a mystic. In 1908, Wright personally gave Tolstoy a letter signed by over 700 English fans. Wright noticed Tolstoy seemed calm, but Tolstoy later wrote in his diary that he didn't want to be bothered with such things at his old age. Later, Wright helped Tolstoy's secretary, Vladimir Chertkov, and his family when they moved to England.

Wright also welcomed famous Russian writers like Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Nabokov, and Alexey Tolstoy to London. He introduced them to English writers and publishers. He was an important member of the Anglo-Russian Committee. This group often told the British public about political problems in Russia. Before World War I, he was active in Russian politics. In 1908, Wright, Henry Nevinson, and Peter Kropotkin tried to raise money to help a Russian revolutionary named Maria Spiridonova escape from prison in Siberia. She had been sentenced to life for political reasons, but she chose to stay. During the Russian Civil War, Wright joined the British Committee for Aiding Men of Letters and Science in Russia. He also helped publish important documents about the last years of the House of Romanov (the Russian royal family) and the revolutions of 1917.

Later Years

When he was 57, Wright married Constance Metcalfe Tyrrell Lewis (1864-1949) on February 20, 1919. She was the widow of Edward Tyrrell Lewis. Wright passed away at his home in London on March 7, 1940, at the age of 77. He is buried in Mill Hill Cemetery, Paddington. A drawing of him by Rothenstein was given to the London Library by his step-daughter in 1963.

Images for kids

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |