Almroth Wright facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Almroth Wright

|

|

|---|---|

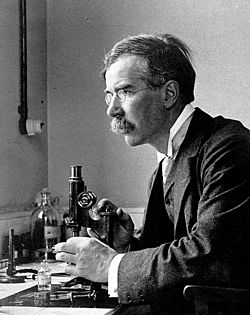

Wright c. 1900

|

|

| Born | 10 August 1861 Middleton Tyas, Yorkshire, England

|

| Died | 30 April 1947 (aged 85) Farnham Common, Buckinghamshire, England

|

| Alma mater | Trinity College Dublin |

| Known for | vaccination through the use of autogenous vaccines |

| Awards | Buchanan Medal (1917) Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | bacteriology immunology |

| Institutions | Netley Hospital St Mary's Hospital, London |

Sir Almroth Edward Wright (born August 10, 1861 – died April 30, 1947) was a British scientist. He studied bacteriology, which is the study of tiny living things called bacteria, and immunology, which is the study of how our bodies fight off diseases.

He is famous for creating a way to protect people from typhoid fever using inoculation (a type of vaccine). He also realized early on that using too many antibiotics could make bacteria become resistant to them. He was a strong supporter of preventive medicine, which means stopping diseases before they start.

Contents

Biography

Wright was born in a small town called Middleton Tyas in England. His family had roots in both England, Ireland, and Sweden. His father was a church leader, and his mother's father was in charge of the Swedish Royal Mint. His younger brother became a librarian in London.

In 1882, Wright finished his studies at Trinity College Dublin with top honors in literature. At the same time, he also studied medicine and graduated in 1883. In the late 1800s, he worked with the British army to create vaccines and encourage people to get immunized.

He married Jane Georgina Wilson in 1889, and they had three children.

Research and Discoveries

In 1902, Wright started a research department at St Mary's Hospital in London. Here, he developed a system to protect people from typhoid fever. He also helped connect two big ideas about how our bodies fight disease. He showed that a substance in the blood, which he called opsonin, works with special cells called phagocytes to fight off germs.

During World War I, many soldiers were getting sick from diseases that could have been prevented. Wright convinced the army to produce 10 million vaccine doses for the troops fighting in France. He even set up a research lab near the front lines. After the war, he returned to St Mary's Hospital and worked there until he retired in 1946. Many famous scientists followed in his footsteps at St Mary's, including Sir Alexander Fleming, who later discovered penicillin. Wright became a member of the important Fellow of the Royal Society in 1906.

Important Ideas

Wright was one of the first to warn that using antibiotics too much could lead to bacteria becoming resistant. This is a big problem we face today. He also believed strongly in preventive medicine, focusing on ways to stop people from getting sick in the first place.

He had some unusual ideas too. He thought that tiny living things (microorganisms) were just "vehicles" for disease, not the actual cause. This idea earned him nicknames like "Almroth Wrong" from people who disagreed with him.

Wright also suggested that doctors should learn about logic as part of their training, but this idea was not adopted. He pointed out that even famous scientists like Louis Pasteur and Fleming sometimes found cures for diseases they weren't even looking for.

He also believed in a theory called the Ptomaine theory, which incorrectly stated that poorly preserved meat caused Scurvy. This theory was popular when explorer Robert Falcon Scott went to the Antarctic in 1911. However, in 1932, scientists discovered that scurvy is actually caused by not getting enough Vitamin C.

Today, there is a ward (a section of a hospital) named after him at St Mary's Hospital in London.

Women's Suffrage

Sir Almroth Wright had very strong opinions against women being allowed to vote. He wrote a book in 1913 called The Unexpurgated Case Against Woman Suffrage. In this book, he argued that women's minds were different from men's and not suited for public and social issues. He also spoke out against women having professional careers. Many people, including writers like Rebecca West and May Sinclair, strongly disagreed with his views and wrote articles criticizing him. His ideas on this topic are now seen as outdated.

Bernard Shaw

Wright was good friends with the famous Irish writer George Bernard Shaw. Shaw even based a character, Sir Colenso Ridgeon, on Wright in his play The Doctor's Dilemma (1906). This play came from conversations between Shaw and Wright.

Shaw often joked about Wright's high reputation, sometimes calling him "Sir Almost Right." They had many lively discussions. In one famous conversation, when asked what doctors should do if there were too many sick patients, Wright replied, "We should have to consider which life was worth saving." This idea became the main "dilemma" in Shaw's play.

Shaw also included Wright in another play and used his ideas about how bacteria change. Even though they were friends, Shaw strongly disagreed with Wright's views on women's rights and thought they were absurd.

Awards

Sir Almroth Wright received many honors during his lifetime. He was recognized 29 times for his work, including a knighthood, several honorary doctorates, and many medals and prizes. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize 14 times between 1906 and 1925.

Some of his notable awards include:

- 1906: He was made a Knight.

- 1906: He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.

- 1908: He received the Fothergill Gold Medal.

- 1917: He was awarded the Buchanan Medal by the Royal Society of London.

- 1919: He became a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Works

Wright's scientific work can be divided into three main periods:

- Early Phase (1891–1910): During this time, he published many articles in medical journals and gave lectures. His work focused on blood, infections, and early ideas about vaccines.

- A short treatise on anti-typhoid inoculation (1904)

- War Phases (1914–1918 and 1941–1945): During both World Wars, his work focused on treating wounds and infections related to war injuries.

- Philosophy Phase (1918–1941 and 1945–1947): In his later years, he wrote more philosophical works, sharing his thoughts on logic, equality, and how science should be done.

- The Unexpurgated Case against Woman Suffrage (1913)

He also wrote handbooks on how to use microscopes and other lab techniques.

See also

- Frederick F. Russell

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |