Charles Young (United States Army officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Young

|

|

|---|---|

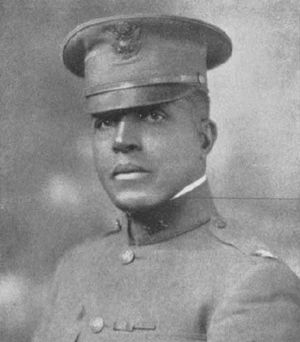

Young in 1919

|

|

| Born | March 12, 1864 Mays Lick, Kentucky, US |

| Died | January 8, 1922 (aged 57) Lagos, Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Years of service | 1889–1922 |

| Rank | Brigadier General (posthumous) |

| Unit | |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

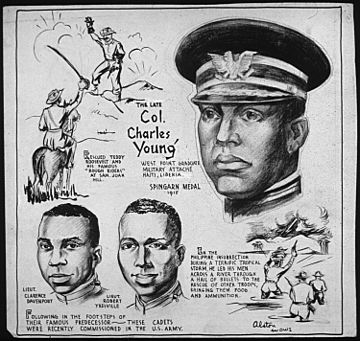

Charles Young (March 12, 1864 – January 8, 1922) was an amazing American soldier. He broke many barriers for African Americans in the military. He was the third African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy.

He was also the first black U.S. national park superintendent. He became the first black military attaché and the first black man to reach the rank of colonel in the U.S. Army. Until his death in 1922, he was the highest-ranking black officer in the regular army.

In 2022, he was given an even higher rank after his death: Brigadier General. This honored his great service and the challenges he faced because of racism. A special ceremony was held at West Point to celebrate this.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Charles Young was born into slavery in 1864 in Mays Lick, Kentucky. His parents were Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen. In 1865, his father escaped slavery and joined the Union Army. This service earned freedom for Gabriel and his wife. Their freedom was made sure by the 13th Amendment after the American Civil War.

The Young family moved to Ripley, Ohio, in 1866. They believed there would be better opportunities there. Charles Young went to the all-white high school in Ripley. He was the only African American student there. He graduated in 1880 at the top of his class. After that, he taught at the new black high school in Ripley for several years.

West Point Challenges

In 1883, Young took a test to become a cadet at West Point. He scored the second highest in his area. But the person who scored first decided not to go. So, Charles Young went to West Point in 1884.

He was one of the first African Americans to attend and graduate from West Point. He faced many challenges, including unfair treatment from other students and teachers. He had to repeat his first year because he struggled with math. He later passed an engineering class with help from a tutor. Young was very good at languages and learned to speak several.

Life at West Point was very hard for Young. He experienced a lot of racism. Other cadets often treated him badly. He was given many demerits, which are like punishments. While other students were called by their last names, Young was often called "Mr. Young." This was a fake way of showing respect.

Young often felt lonely at West Point. A white classmate later said that Young would talk to servants in German. This helped him feel more connected to people. By the end of his five years, the unfair treatment lessened. Some classmates started to see past his skin color. Even so, Young said his time at West Point was very difficult.

Military Career Beginnings

Young graduated from West Point in 1889. He became a second lieutenant. He was the third black man to graduate from West Point at that time. He was first sent to the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Later, he served with the Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment in Nebraska.

For 28 years, he mainly served with black troops. These were the Ninth and Tenth U.S. Cavalry, known as the "Buffalo Soldiers." The military was segregated by race until 1948.

Family Life

Charles Young married Ada Mills on February 18, 1904, in Oakland, California. They had two children. Their son, Charles Noel, was born in Ohio in 1906. Their daughter, Marie Aurelia, was born in 1909 when the family was in the Philippines.

Key Military Service

Young started his service in the American West. From 1889 to 1890, he was at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. From 1890 to 1894, he was at Fort Duchesne, Utah.

In 1894, Lieutenant Young was sent to Wilberforce University in Ohio. This was a college mainly for black students. He led the new military science department there. He taught for four years and became good friends with W. E. B. Du Bois.

When the Spanish–American War began, Young was promoted to major. He commanded the 9th Ohio Infantry Regiment, an African-American unit. This was very important because it was one of the first times a black officer commanded a large U.S. Army unit. The war ended before his unit could go overseas. He was later promoted to captain in the 9th Cavalry Regiment in 1901.

National Park Superintendent

In 1903, Captain Young was put in charge of Sequoia and General Grant national parks. This made him the first black superintendent of a national park. At that time, the military managed all national parks.

Young's biggest achievement was building roads in the park. His troops built a wagon road to the Giant Forest, where the world's largest trees grow. They also built a road to the famous Moro Rock. This made it easier for visitors to enjoy the park. Young recommended that the government buy more land for the park.

Other Important Assignments

In 1904, Young became one of the first military attachés. He served in Haiti for three years. His job was to gather information to help keep the government stable.

In 1908, Young went to the Philippines for a second time. He commanded a group of troops there. After returning to the U.S., he served in Wyoming for two years.

In 1912, Young became the military attaché to Liberia. He was the first African American to hold this job. He advised the Liberian government and helped build the country's roads and buildings. For his work, he received the Spingarn Medal in 1916. This award honors the highest achievements by an African American.

Young also wrote a book called The Military Morale of Nations and Races. In it, he argued that all people, including African Americans, could be brave soldiers. He believed that if a country offered equal rights, its people would fight harder.

During the Pancho Villa Expedition in Mexico in 1916, Major Young led the 2nd Squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry. He led a successful charge against Pancho Villa's forces. His troops won without losing a single man. Because of his great leadership, Young was promoted to lieutenant colonel in September 1916. He then commanded Fort Huachuca in Arizona. He was the first African American to reach the rank of colonel in the U.S. Army.

Unfair Retirement

As the United States was about to enter World War I, Young had a good chance to become a brigadier general. However, many white officers did not want a black officer to outrank them. The War Department removed Young from active duty. They said it was because of his high blood pressure. Young was put on the inactive list as a colonel in June 1917.

Young tried to get back into active service. He even rode his horse from Ohio to Washington, D.C., to prove he was fit. In November 1918, he was put back on active duty as a colonel. But he was not allowed to command troops in Europe.

Death and Burial

In late 1921, Charles Young became very ill while on a mission in Nigeria. He died of a kidney infection in Lagos on January 8, 1922. His body had to be buried in Lagos for a year. Young's wife and other important African Americans demanded that his body be brought back to the U.S. for a proper military burial.

More than a year later, his body was brought back to America. He received a hero's welcome in New York. Many people came to honor his long military career. He was given a full military funeral and buried at Arlington National Cemetery. He was a respected public figure because of his unique achievements. His death was even reported in The New York Times.

Honors and Lasting Legacy

Honors Received

Charles Young received many honors during his life. He was praised for his work as superintendent of Sequoia National Park. In 1912, he became an honorary member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. In 1916, the NAACP gave him the Spingarn Medal for his work in Liberia and the U.S. Army.

After his death, he received more honors. In 2020, he was made an honorary Brigadier General in Kentucky. In 2022, he was officially promoted to honorary Brigadier General by the U.S. government. A ceremony was held to celebrate this important recognition.

His Lasting Legacy

Many efforts have been made to remember Charles Young. His obituary in The New York Times showed his national importance. His funeral was one of the few held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery.

Schools have been named after him, like the Charles Young School in Louisville, Kentucky. A park in Louisville also bears his name. In Washington, D.C., Charles E. Young Elementary School was named in his honor.

In 1974, the house where Young lived in Ohio was named a National Historic Landmark. This recognized his historical importance. In 2013, President Barack Obama made Young's house a national monument. It is now called the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument. In 2018, a highway in California was named the Colonel Charles Young Memorial Highway. This highway's end is in Sequoia National Park, where Young served as superintendent.

In Art and Literature

Charles Young is also remembered in African-American art and literature. Countée Cullen wrote a poem in 1925 called “In Memory of Colonel Charles Young.” The poem suggests that Young's legacy would inspire future generations. It says that from his struggles, "A tree with tongues will grow." This means his actions would lead to many voices speaking out.

His close friend, W. E. B. Du Bois, spoke at Young's funeral. Du Bois said that "the life of Charles Young was a triumph of tragedy." This means Young achieved great things despite facing many hardships. There is also a painting of Young by J. W. Shannon. It shows him with a bright background, making him look like a hero. This painting is at The National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Ohio.

Military Awards

Brigadier General Young received these service medals:

| 1st row | Indian Campaign Medal | Spanish Campaign Medal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd row | Philippine Campaign Medal | Mexican Service Medal | World War I Victory Medal | ||||||

Dates of Rank

- Cadet, United States Military Academy – June 15, 1884

- 2nd Lieutenant, 10th Cavalry – August 31, 1889 (transferred to 9th Cavalry October 31, 1889)

- 1st Lieutenant, 7th Cavalry – December 22, 1896 (transferred to 9th Cavalry October 1, 1897)

- Major (Volunteers), 9th Ohio Colored Infantry – May 14, 1898

- Mustered out of Volunteers – January 28, 1899

- Captain, 9th Cavalry – February 2, 1901

- Major, 9th Cavalry – August 28, 1912 (transferred to 10th Cavalry October 19, 1915)

- Lieutenant Colonel – July 1, 1916

- Retired as Colonel – June 22, 1917

- Reinstated as Colonel – November 6, 1918

- Posthumously promoted to honorary Brigadier General (Kentucky) – February 11, 2020

- Posthumously promoted to honorary Brigadier General (federal) – February 1, 2022

Images for kids

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |