Science History Institute facts for kids

The Science History Institute in Philadelphia in October 2019

|

|

| Former name | Center for the History of Chemistry (1982–1992) Chemical Heritage Foundation (1992 – February 1, 2018) |

|---|---|

| Established | 22 January 1982 |

| Location | 315 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 19106, U.S. |

| Key holdings | Alchemy, History of chemistry, History of science, Instrumentation |

| Founder | Arnold Thackray |

| Public transit access | |

The Science History Institute is a special place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that helps people learn about the history of science. It’s a museum, library, and research center all rolled into one. It tells the story of how science has changed our world.

The Institute started in 1982 as the Center for the History of Chemistry. It was a team effort between the American Chemical Society and the University of Pennsylvania. Over the years, it grew and changed its name a couple of times. In 2018, it became the Science History Institute to show that it covers all kinds of science history, including biology and medicine.

The Institute focuses on the history of chemistry, technology, and how science affects our daily lives. It even looks at the connection between science and art. It supports researchers who study science history and records interviews with famous scientists to save their stories.

Contents

How the Institute Began

The idea for a museum and library about chemistry in the United States is very old. It was first discussed at a meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS) way back in 1876.

The idea came back to life in 1976. A professor named Arnold Thackray believed Philadelphia was the perfect place for it. With help from chemist John C. Haas and companies like Dow Chemical Company and DuPont, the plan moved forward. In 1982, the Center for the History of Chemistry officially opened in a few basement rooms at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Center's first goals were to record the stories of important chemists and to find and list important scientific papers all over the country. Soon, other science groups joined in to help support the Center.

Growing into a Foundation

In the 1980s, a famous inventor named Arnold Orville Beckman gave a large donation. This helped the Center grow into a bigger research institute. It was renamed the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for the History of Chemistry.

A few years later, a chemical engineering professor named Donald F. Othmer and his wife Mildred gave another large donation. This money was used to create the Othmer Library of Chemical History. The library received thousands of books from The Chemists' Club in New York, making its collection even bigger.

In 1992, the organization changed its name to the Chemical Heritage Foundation. It bought an old bank building on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia and moved there in 1996. This new, permanent home meant it could finally build a museum for everyone to visit.

Building the Museum

Having a permanent building allowed the foundation to start collecting and showing interesting objects. The museum wanted to display things that told the story of science.

One major focus was scientific instruments. The museum began collecting important tools that changed science, like early pH meters (which measure acidity) and spectrophotometers (which measure light). In 2002, the company PerkinElmer donated hundreds of instruments, which greatly expanded the collection.

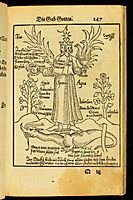

The museum also became home to one of the world's largest collections of art about alchemy. Alchemists were early scientists who tried to turn metals into gold. Their experiments helped start the science of chemistry. The collection includes over 90 paintings and 200 drawings showing alchemists at work.

In 2008, the museum opened its main exhibit, called Making Modernity. It was designed to be like an "art gallery for science." It shows off amazing objects from the Institute's collections, including old books, scientific tools, and even everyday products that were created through science.

The Institute's Amazing Collections

The Science History Institute has many fascinating collections that tell the story of science.

Books and Archives

- The Othmer Library: This library holds thousands of rare and important books about the history of chemistry. Some books are over 500 years old! They show how our understanding of science has grown over time.

- Archives: The archives are like a treasure chest of scientific history. They contain the notes, letters, and papers of famous scientists and companies. Researchers from all over the world come to study these unique documents.

Pictures and Art

- Photographs: The Institute has over 20,000 photos of famous scientists, old laboratories, and important events in science history. There are formal portraits and fun snapshots, like pictures of scientists on a fishing trip.

- Fine Art: The art collection mainly features paintings of alchemists. These paintings show how alchemists worked and how their experiments laid the groundwork for modern chemistry.

Objects and Artifacts

The Institute collects objects that you can see and touch. These artifacts help bring the history of science to life.

- Instruments: The collection includes groundbreaking tools like an early mass spectrometer used by Nobel Prize winner John B. Fenn.

- Chemistry Sets: The museum has one of the best collections of chemistry sets in the world, with about 100 different sets from many countries.

- Bakelite: There is a special collection of items made from Bakelite, one of the first plastics ever invented.

- Art from the Institute's collection

Magazine and Programs

The Science History Institute publishes an online magazine called Distillations. It features interesting stories about the history of science for everyone to enjoy.

The Institute also offers fellowships, which are special programs that allow students and scholars to come and do research using its amazing collections.

Awards

Each year, the Science History Institute gives out awards to honor people who have made great contributions to science and technology. These awards celebrate the achievements of researchers, business leaders, and inventors. Some of the awards include the Othmer Gold Medal and the Petrochemical Heritage Award.

See also

- Burndy Library

- Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

- Ullyot Public Affairs Lecture

- Whipple Museum of the History of Science

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |