Chimes at Midnight facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chimes at Midnight |

|

|---|---|

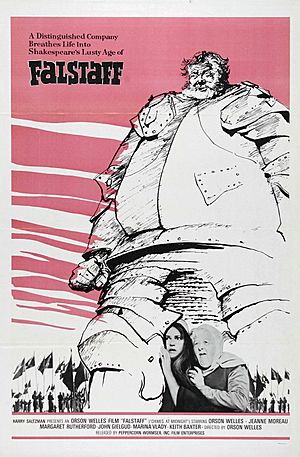

U.S. theatrical release poster

|

|

| Directed by | Orson Welles |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Orson Welles |

| Narrated by | Ralph Richardson |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Angelo Francesco Lavagnino |

| Cinematography | Edmond Richard |

| Editing by | Frederick Muller |

| Studio |

|

| Distributed by | Peppercorn-Wormser Film Enterprises (United States) |

| Release date(s) | May 8, 1966 (Cannes Film Festival) November 17, 1966 (Switzerland) |

| Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $800,000 |

| Money made | 516,762 admissions (France) |

Chimes at Midnight (also known as Falstaff) is a 1966 historical drama film. It was directed by and stars Orson Welles. This movie was made by companies from Spain and Switzerland.

The story is about William Shakespeare's famous character, Sir John Falstaff. It also explores the special friendship he has with Prince Hal. Prince Hal is the future king. He has to choose between being loyal to his father, King Henry IV, and his friend, Falstaff. Orson Welles said the main idea of the film was "the betrayal of friendship."

Welles plays Falstaff. Keith Baxter plays Prince Hal. John Gielgud is King Henry IV. The script uses lines from five of Shakespeare's plays. These are mostly Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2. The film also uses parts of Richard II, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. The story is told by Ralph Richardson. His narration comes from old writings by Raphael Holinshed.

Orson Welles had tried to make this story before. He created a stage play called Five Kings in 1939. Later, in 1960, he brought it back as Chimes at Midnight. Neither play was a big hit. But Welles always wanted to play Falstaff. He thought it was his life's dream. So, he turned the project into a film. Making the movie was hard. Welles struggled to get enough money. The film was shot in Spain from 1964 to 1965. It first showed at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. There, it won two awards.

At first, many film critics didn't like Chimes at Midnight. But now, it is seen as one of Welles' best films. Welles himself called it his greatest work. He felt a strong connection to Falstaff. He called Falstaff "Shakespeare's greatest creation." Some people who study films compare Falstaff to Welles. Others see a likeness between Falstaff and Welles' father. For a long time, it was hard to watch the film legally. This was because of arguments over who owned it. But recently, it has become easier to find and watch.

Contents

The Story of Chimes at Midnight

The movie begins with John Falstaff and Justice Shallow talking by a warm fire. They remember old times. Meanwhile, King Henry IV of England is now king. He took the throne from Richard II. Richard II's true heir, Edmund Mortimer, is a prisoner. Mortimer's family, the Percys, want King Henry to free him. When the King says no, the Percys start planning to overthrow him.

King Henry IV is unhappy. His son, Prince Hal, spends most of his time at the Boar's Head Tavern. He is often with Falstaff, who acts like a father figure to him. Falstaff believes they are gentlemen. But Hal warns Falstaff that he will one day leave this life behind.

One morning, Hal, Falstaff, and their friends plan a prank. They pretend to rob some travelers. After Falstaff and his friends take the treasure, Hal and another friend, Poins, jump out. They are in disguises. They take the stolen treasure from Falstaff as a joke.

Back at the tavern, Falstaff tells an exaggerated story of the robbery. Hal and Poins point out the holes in his story. Then, they reveal their joke. To celebrate, Falstaff and Hal pretend to be King Henry. They wear a cooking pot as a crown. Falstaff, pretending to be the King, scolds Hal for his bad friends. But he calls Falstaff his only good friend. Hal, pretending to be the King, calls Falstaff a "misleader of youth."

Hal visits his father, the King. Henry scolds Hal for his troublesome behavior. The King warns Hal about Hotspur's growing army. Hotspur is a Percy. Hal promises his father that he will defend him and make things right. The King's army, including Falstaff, marches off to war. Before the battle, King Henry offers to forgive Hotspur's men if they surrender. Hal promises to fight Hotspur himself. But Hotspur's uncle, Worcester, lies to Hotspur. He tells him that Henry plans to execute all rebels.

The two armies meet at the Battle of Shrewsbury. Falstaff hides for most of the fight. After a long, bloody battle, the King's men win. Hotspur and Hal fight alone. Hal kills Hotspur. King Henry sentences Worcester to death. Falstaff brings Hotspur's body to Henry. He claims he killed Hotspur. But Henry doesn't believe him. He looks at Hal with disapproval. He is upset about the company Hal keeps.

The narrator explains that all of Henry IV's enemies were defeated by 1408. But King Henry's health gets worse. At the castle, Henry is upset to hear that Hal is with Falstaff again. He collapses. Hal visits the castle. He realizes his father is very sick. Hal promises Henry he will be a good king. Henry finally trusts Hal. He gives him advice on how to rule. Henry dies, and Hal becomes King Henry V.

Falstaff, Shallow, and Silence are by a fire, just like in the first scene. They hear that King Henry IV has died. They also hear that Hal's coronation will be that morning. Falstaff is very excited. He goes to the castle. He thinks he will become an important nobleman under King Henry V. At the coronation, Falstaff can't control his excitement. He interrupts the ceremony. He announces himself to Hal. But Hal turns his back on Falstaff. He says he is done with his old life. Falstaff looks at Hal with mixed feelings of pride and sadness. The new king banishes Falstaff. The coronation continues inside the castle. Falstaff walks away, believing he will be called for later. That night, Falstaff dies at the Boar's Head Tavern. His friends mourn him. They say he died of a broken heart. Hal went on to become a good and noble king.

Main Actors

- Orson Welles as Sir John Falstaff, a knight and a father-figure to Prince Hal.

- Keith Baxter as Prince Hal, the Prince of Wales and the future King of England.

- John Gielgud as King Henry IV, the King of England.

- Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly, who runs the Boar's Head Tavern.

- Alan Webb as Justice Shallow, an old friend of Falstaff.

- Walter Chiari as Justice Silence, another friend.

- Michael Aldridge as Pistol, a friend of Falstaff.

- Tony Beckley as Ned Poins, a friend of Falstaff and Hal.

- Charles Farrell as Bardolph, a friend of Falstaff and Hal.

- Patrick Bedford as Nym, a friend of Falstaff and Hal.

- José Nieto as Earl of Northumberland, a rebel against the King.

- Keith Pyott as the Lord Chief Justice.

- Fernando Rey as Earl of Worcester, Northumberland's brother.

- Norman Rodway as Henry Percy, called Hotspur, Northumberland's son.

- Marina Vlady as Kate Percy, Hotspur's wife.

- Andrew Faulds as Earl of Westmorland, loyal to the King.

- Jeremy Rowe as Prince John, Henry IV's second son.

- Beatrice Welles as Falstaff's Page, a young servant.

- Ralph Richardson as The Narrator (voice).

How the Film Was Made

Orson Welles first thought about making Chimes at Midnight when he was a school student in 1930. He tried to put on a long play combining several of Shakespeare's history plays. He always wanted to tell this story.

Early Stage Plays

The film started as a stage play called Five Kings in 1939. Welles wrote and partly directed it. It was a very ambitious play. It told the stories of several English kings from Shakespeare's plays. Welles played Falstaff in this play. The play had a very complex spinning set. But it was too long and had many problems. It closed after only a few performances.

Welles returned to the project in 1960. This time, it was called Chimes at Midnight. It was performed in Belfast and Dublin. Welles again played Falstaff. He focused more on the friendship between Falstaff and Prince Hal. This version also had problems and closed early. Welles later said he was bored with it. He told actor Keith Baxter that it was just a rehearsal for the movie.

Making the Movie

In 1964, Welles met a Spanish film producer named Emiliano Piedra. Piedra wanted to work with Welles. But he thought a Shakespeare film wouldn't make much money. He suggested Welles make a film of Treasure Island instead. Welles agreed, but only if he could also make Chimes at Midnight at the same time. Welles actually didn't plan to make Treasure Island. He built sets that could be used for both films. For example, the Boar's Head Tavern could also be the Admiral Benbow Inn. He also cast actors for both films.

Welles said the Boar's Head Tavern was the only full set built for the film. He designed and painted all the film's costumes. The title Chimes at Midnight comes from Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part 2. In the play, Falstaff says, "We have heard the chimes at midnight, Master Shallow." This phrase makes people think of sadness and time passing.

Filming took place in Spain from September 1964 to April 1965. The budget was $800,000. Actors like Jeanne Moreau and John Gielgud were only available for a few days. Margaret Rutherford was available for four weeks. Welles joked that sometimes they had to use stand-ins for actors who weren't there. Filming locations included Colmenar, Cardona, and Madrid. The battle scenes were filmed in Madrid's Casa de Campo Park.

Welles ran out of money in December. Filming stopped while he looked for more funding. He got more money from Harry Saltzman. Production started again in late February. Welles finished the film by April. He shot close-ups and Falstaff's speeches. Other filming locations included the Chateau Calatañazor and the city of Ávila.

After Filming

The film's sound was added later. Actors Fernando Rey and Marina Vlady had their voices re-recorded by other actors because of their strong accents. Welles liked Margaret Rutherford's performance so much that he kept her original voice, even with background noise. The music was composed by Angelo Francesco Lavagnino. He had worked with Welles before. The music uses old medieval dance tunes. Welles had to finish editing the film quickly. This was because the head of the Cannes Film Festival wanted to include it right away.

Film Style

How It Was Filmed

Welles originally wanted the whole film to look like old medieval pictures. But only the opening titles use this style. The most famous part of the film is the Battle of Shrewsbury scene. Welles only had about 180 extra actors. He used clever editing to make it look like thousands of soldiers were fighting. He filmed the battle scenes in long shots. Then, he cut them into many small pieces. This created a fast and chaotic feeling. It took ten days to film these scenes and six weeks to edit them. The final battle scene is only six minutes long. Welles used hand-held cameras, wide lenses, and quick movements. This made the scene feel very energetic and messy.

Many film critics say the Battle of Shrewsbury scene is a statement against war. It has been compared to other anti-war films. One expert said the battle scenes were "some of the finest, truest, ugliest scenes of warfare ever shot."

Sound in the Film

Because of money problems, the sound recorded during filming and after was not always perfect. This, along with Welles' fast camera movements, sometimes makes Shakespeare's words harder to understand. Welles often filmed scenes with actors' backs to the camera. This was probably because the actors weren't always present. This also caused sound problems. During the Battle of Shrewsbury, Welles used many layers of sound. You can hear swords clanking, soldiers grunting, bones breaking, and boots in the mud. This all added to the chaos of the scene.

Welles and Falstaff

Welles' Thoughts on Falstaff

Welles believed Falstaff was "Shakespeare's greatest creation." He also said it was "the most difficult part I ever played in my life." Actor Keith Baxter thought making this film was Welles' dream. Welles wanted to show Falstaff as a sad character. He said Falstaff's humor came from wanting to please the prince. Welles felt that Falstaff had the potential for greatness. Over the years, Welles' respect for Falstaff grew. By the time he made the film, he focused on the relationships between Falstaff, Hal, and King Henry IV. He believed the main idea was "the betrayal of friendship." Welles called Hal's rejection of Falstaff "one of the greatest scenes ever written." He said the whole movie was leading up to that moment.

Welles said the film was not just about Falstaff. It was about the end of "Merrie England." This was a mythical idea of a happy, simple, old England. Welles believed it was more than just Falstaff dying. It was "the old England dying and betrayed." Many film experts say Welles' work often shows a longing for an ideal past. Welles said that even if the "good old days" never existed, the fact that we can imagine them shows the strength of the human spirit. Welles also called Falstaff "the greatest conception of a good man." He said that the more he understood Falstaff, the less funny he seemed.

Welles' Personal Connection to Falstaff

Keith Baxter compared Welles to Falstaff. Both often had money problems. Both sometimes used clever tricks to get what they needed. And both were often cheerful and fun-loving. Film expert Jack Jorgens also compared Welles to Falstaff. He said that Welles, like Falstaff, was a great artist who faced many challenges. He often had to work on films with little money. He had many projects that never happened. So, the story of an aging, witty character who is cast aside might have felt very personal to Welles. Some people have even said that Hal rejecting Falstaff in the film is like Hollywood rejecting Welles.

Images for kids

-

Orson Welles as Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight.