Choe Chiwon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

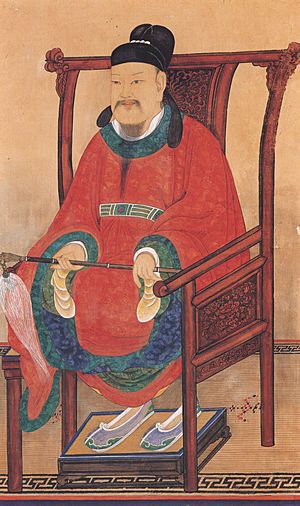

Choe Chiwon

|

|

|---|---|

| 崔致遠 | |

|

|

| Born | 857 |

| Died | unknown |

| Occupation | Philosopher, poet |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul |

최치원

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Choe Chiwon |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ch'oe Ch'iwŏn |

| Art name | |

| Hangul |

해운, 고운

|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Hae-un, Goun |

| McCune–Reischauer | Haeun, Koun |

Choe Chiwon (Korean pronunciation: [tɕʰʷe tɕʰiwʌn]; 857–10th century) was a famous Korean thinker and writer. He lived during the late Unified Silla period (668-935). Choe Chiwon spent many years studying in Tang China. He even passed their important government exams and worked in a high position there.

Afterward, he returned to Silla. He tried to make big changes to the government, but it was too late. Silla was already becoming weaker. In his later years, Choe became more interested in Buddhism. He lived like a wise hermit near Korea's Haeinsa temple.

Choe Chiwon was also known by his special names. These were Haeun, meaning "Sea Cloud," and Goun, meaning "Lonely Cloud." Today, many people see him as the first important person of the Gyeongju Choe clan.

Contents

Early Life and Study in China

Choe Chiwon was born in 857 in Gyeongju. This was the capital city of Silla. He belonged to a special group called "head rank six" (yukdupum). This group was part of Silla's strict bone rank system. People in this group had limits on how high they could rise in government jobs.

As Silla started to decline, many "head rank six" members looked for new chances. Some became Buddhist monks. Others studied Confucianism, which was a way of thinking about government and society. China had a government based on Confucian ideas. Silla wanted to use some of these ideas too. This meant Silla needed many educated officials. The king supported "head rank six" students to fill these roles.

In the 9th century, many Silla students wanted to study in China itself. They went to the Tang capital, Chang'an (now Xi'an). The Choe family of Gyeongju had strong ties with the Silla king. Because of this, many Choe family members went to China to study. Their goal was to pass China's civil service exam. Then they would return to serve the Silla court.

According to an old history book, Samguk Sagi, Choe was twelve years old in 869. His father sent him to study in Tang China. His father told him he had to pass the Chinese imperial examination within ten years. If not, he would no longer be his son. Choe did pass the highest exam, called jinshi, within that time. He then got a job in a Chinese city.

Choe worked in China for almost ten years. He even became close with the Chinese Emperor Xizong of Tang. Choe also helped a Chinese general fight against a big rebellion. After the rebellion ended, Choe wanted to go home. He wrote a poem about missing his family and homeland. He had not seen them in a decade.

The Samguk Sagi says Choe asked the Tang emperor to return to Silla. He wanted to see his aging parents. The emperor agreed, and Choe returned home in 885. He was 28 years old.

Trying to Make Changes

When Choe returned to Silla, he became a teacher at the Confucian Hallim Academy. He held different jobs, like Minister of War. He also led several regional areas. In 893, he was supposed to go on a trip to Tang China. But Silla had problems like famine and unrest. So, he could not go. Tang China fell apart soon after, and Choe never saw China again.

As a "yukdupum" member, Choe hoped to make big changes in Silla. He was not the first to try. But his efforts are well-known in Korean history. In 894, Choe gave Queen Jinseong (who ruled from 887-897) his "Ten Urgent Points of Reform." These were ideas to fix Silla. But like earlier attempts, his ideas were not listened to.

By the time Choe came back, Silla was falling apart. The king's power was very weak. Powerful families fought among themselves. Even worse, local warlords controlled the countryside. They had their own armies.

Later Life and Retirement

We do not have many records about Choe's middle and later years. Around the year 900, Choe stopped working for the government. He began to travel around Korea. The Samguk Sagi says he lived like a wise person in the mountains. He built small houses by rivers and planted trees. He read books, wrote history, and made poems about nature. He lived in places like Namsan in Gyeongju and Ssanggye Temple in Jirisan.

The Haeundae District in modern Busan is named after Choe's pen-name, Haeun. He loved that place and built a pavilion there. A carving of his writing on a rock is still there today.

Eventually, Choe settled at Haeinsa Temple. His older brother was the head monk there. In his later years, Choe wrote many long stone inscriptions. These were stories about Silla's famous Buddhist priests. They are now important sources of information about Buddhism in Silla.

There is a famous story about Choe sending a poem to Wang Geon. Wang Geon was the founder of the Goryeo kingdom. Choe supposedly believed Wang Geon was meant to rule after Silla. So, he secretly sent a poem showing his support. The poem said, "The leaves of the Cock Forest [Silla] are yellow, the pines of Snow Goose Pass [Goryeo] are green." This meant Silla was fading, and Goryeo was strong. However, this story appeared long after Choe died. Some modern experts think Choe, who loved Silla, did not write it. They believe it was added by the Goryeo dynasty to make their rule seem more rightful.

We do not know when Choe died. He was still alive in 924, when he made one of his stone carvings. One amazing story says his straw slippers were found near Mt. Gaya (Gayasan). This is where Haeinsa is located. The story says Choe became a Daoist immortal and went up to the heavens.

How People Saw Him Later

After Choe's death, people saw him in different ways. As Korea became more focused on Confucianism, especially during the Joseon dynasty, Choe became a highly respected Confucian scholar. His portrait was placed in the national Confucian temple. King Hyeonjong (who ruled from 1009-1031) gave him the special title "Marquis of Bright Culture."

Choe was also admired as a poet. Many of his poems, written in Chinese, have survived. Over time, many folk tales grew around Choe. These stories gave him amazing deeds and magical powers.

In the late 1800s, some Korean thinkers started to look at their history differently. They felt Korea had relied too much on China. A famous journalist named Shin Chaeho (1880–1936) criticized Choe Chiwon. Shin believed Choe was an example of Koreans being too loyal to China. Shin thought this made Korea's national spirit weaker.

Today, the Gyeongju Choe clan says Choe Chiwon is their founder. The place where his home was in Gyeongju is now a small temple honoring him.

His Writings

Choe's many writings show how important he was in late Silla. They also helped him stay famous for generations. Many of his friends were also talented writers and officials. But their works did not survive as well as his.

Some of Choe's works are now lost. But his surviving writings can be put into four groups:

- Official writings: Letters and reports he wrote while working in Tang China and Silla.

- Private writings: About topics like drinking tea or beautiful nature.

- Poetry: His poems.

- Stele inscriptions: Writings carved on stone monuments.

After Choe returned to Silla in 885, he put his writings together. He gave them to King Heongang. We know what was in that collection, but the whole thing is gone now. What we do have is one part called the Gyeweon Pilgyeong (계원필경, "Plowing the Cassia Grove with a Writing Brush"). This book has ten volumes. It mostly contains official letters and reports he wrote while in China. It also has some private writings.

Many of Choe's poems have survived through other Korean books. The Dongmunseon, a collection of Korean poetry from the Joseon Dynasty, has many of them. Some of his poems are also in the 12th-century Samguk Sagi.

Choe's surviving stone inscriptions are called the Sasan bimyeong (사산비명, “Four mountain steles”). They are all in present-day South Korea:

- Jingamguksa bimyeong (진감국사비명): A monument for Master Jingam of Ssanggye Temple, from 887.

- Daesungboksa bimyeong (대숭복사비명): A monument for Daesungbok Temple, from 885. This one is not complete.

- Nanghyehwasang bimyeong (낭혜화상비명): A monument for Master Ranghye of Seongju Temple, from 890.

- Jijeungdaesa bimyeong (지증대사비명): A monument for Master Jijeung of Pongam Temple, from 924.

Some people thought Choe wrote the Silla Suijeon. This was the oldest collection of Korean Buddhist tales and fables. But most experts agree he did not write it. One of the stories in it is even about Choe Chiwon himself! Also, some thought he wrote a Confucian teaching book. But experts say the language does not match his style.

See also

- Korean Confucianism

- Munmyo

- Korean philosophy

- Silla