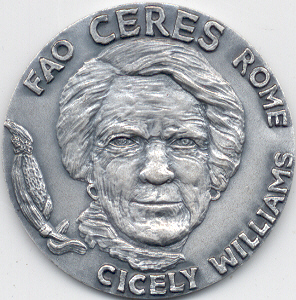

Cicely Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cicely Delphine Williams

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 2 December 1893 Kew Park, Jamaica

|

| Died | 13 July 1992 (aged 98) Oxford, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Somerville College, Oxford, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, King's College Hospital |

| Known for | Discovery of kwashiorkor and advancing the field of maternal and child health in developing nations |

| Awards | OM, CMG, FRCP |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Pediatrics, Nutrition, Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children, World Health Organization, University of Singapore, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine |

Cicely Delphine Williams (2 December 1893 – 13 July 1992) was an important Jamaican doctor. She is famous for discovering and studying kwashiorkor. This is a serious condition caused by severe malnutrition. She also strongly campaigned against using sweetened condensed milk and other artificial milks instead of human breast milk for babies.

Dr. Williams was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford University. She played a huge role in improving health for mothers and children in developing countries. In 1948, she became the first director of Mother and Child Health (MCH) at the new World Health Organization (WHO). She believed that doctors needed to understand a child's home life to truly help them.

Contents

Early Life and Medical Training

Cicely Delphine Williams was born in Kew Park, Jamaica. Her family had lived there for many generations. When she was 13, she moved to England for her education. At 19, she was accepted into Somerville College, Oxford.

She delayed her studies to return to Jamaica. She helped her family after a series of earthquakes and hurricanes. After her father passed away in 1916, Cicely, then 23, went back to Oxford. She began studying medicine. She was one of the first women allowed into the medical program. This was partly because many male students were away fighting in World War I.

Becoming a Children's Doctor

In 1923, at age 31, Williams qualified as a doctor from King's College Hospital. She then worked for two years at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children in Hackney, England. It was there that she decided to specialize in pediatrics, which is the medical care of infants, children, and adolescents.

She realized that to be a good children's doctor, she needed to know about a child's home and family life. This idea became central to her medical work. After World War I ended, it was hard for women doctors to find jobs. Many male doctors were returning home. She worked briefly with Turkish refugees. In 1929, she joined the Colonial Medical Service. She was sent to the Gold Coast, which is now Ghana.

Work in the Gold Coast

In the Gold Coast, Dr. Williams was hired as a "Woman Medical Officer." She didn't like this title because it meant she was paid less than male doctors. Her job was to treat sick babies and children. She also gave advice at local clinics. She saw many children getting sick and dying.

To help more people, she trained nurses to visit homes. She also started "well-baby visits" for the community. These visits helped keep healthy babies well. She also created a patient card system to keep good records. Dr. Williams respected traditional medicine and local knowledge. This was unusual for colonial doctors at the time.

Discovering Kwashiorkor

Dr. Williams noticed that many toddlers, aged two to four, were getting very sick. They often had swollen bellies and very thin arms and legs. Many of these children died, even with treatment. Doctors often thought this condition was pellagra, a vitamin deficiency. But Dr. Williams disagreed.

She performed autopsies to find out more. This was very risky because there were no antibiotics. She even became seriously ill herself. She asked local women what they called this condition. They told her kwashiorkor. She translated this as "disease of the deposed child." This meant the child who was replaced by a new baby.

Her research showed that kwashiorkor was caused by a lack of protein. This happened when young children stopped breastfeeding after a new baby arrived. She published her findings in 1933. However, many doctors did not believe her. They kept treating children for pellagra, even though thousands continued to die. Dr. Williams felt that many doctors didn't take her seriously because she was a woman.

Moving to Malaya

Dr. Williams believed that kwashiorkor was caused by a lack of knowledge. She wanted to combine preventing illness with treating it. This caused disagreements with her bosses. In 1936, she was transferred to Malaya. She was to lecture at the University of Singapore.

Malaya and World War II

In Malaya, Dr. Williams found a different health problem. Many newborn babies were dying. She was very upset to learn that companies were tricking new mothers. They hired women dressed as nurses. These "nurses" told mothers that sweetened condensed milk was better than human breast milk. This practice was illegal in England. But Nestlé was selling this milk in Malaysia. They advertised it as "ideal for delicate infants."

"Milk and Murder" Speech

In 1939, Dr. Williams spoke to the Singapore Rotary Club. The club's chairman was also the president of Nestlé. In her famous speech, titled "Milk and Murder," she said:

- "Misguided propaganda on infant feeding should be punished as the most miserable form of sedition; these deaths should be regarded as murder."

She then managed a health center in Trengganu, Malaya. She was responsible for 23 other doctors and about 300,000 patients.

Internment During the War

In 1941, the Japanese invaded Malaya. Dr. Williams had to escape to Singapore. Soon after, Singapore also fell to the Japanese. She was held in a prison camp called Sime Road. Later, she was moved to Changi Prison with 6,000 other prisoners. She was imprisoned for three and a half years. She became a leader in the camp. This led to her being taken to the Kempe Tai headquarters for six months. There, she faced very harsh conditions, including starvation and mistreatment.

When the war ended in 1945, she was very ill in the hospital. She suffered from dysentery and beriberi. Beriberi left her feet numb for the rest of her life. After returning to England, she wrote a report about the health of women and children in the camp. She noted:

- "20 babies were born, 20 babies were breastfed, 20 babies survived, you can't do better than that".

Later Years and Global Impact

In 1948, Dr. Williams became the head of the new Maternal and Child Health (MCH) division. This was part of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva. Later, she moved back to Malaya. There, she led all maternal and child welfare services in South-East Asia.

In 1950, she led a study on kwashiorkor across 10 countries in Africa. This study found that kwashiorkor was "the most serious and widespread nutritional disorder known." During her time with WHO, she lectured and advised in over 70 countries. She strongly promoted using local knowledge and resources to improve health.

Solving the "Vomiting Sickness"

In 1951, there was an outbreak of "vomiting sickness" in Jamaica. The government asked her to investigate. Between 1951 and 1953, Dr. Williams led this research. Her work helped identify that unripe ackee fruit caused the illness.

From 1953 to 1955, she taught Nutrition at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. In 1960, she became a Professor in Beirut, Lebanon. She worked with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). She helped Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip. She also worked with communities in Yugoslavia, Tanzania, Cyprus, Ethiopia, and Uganda.

Awards and Legacy

In 1965, Dr. Williams received the James Spence Gold Medal. This was for discovering Kwashiorkor and understanding that malnutrition was often due to a lack of knowledge.

In 1968, she was made a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG). She met Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. The Queen asked her where she had been and what she had been doing. Dr. Williams modestly replied, "Many places," and "Mostly looking after children."

In 1986, the University of Ghana gave her an honorary Doctorate of Science. This was for her "love, care and devotion to sick children." Her work in Ghana was so popular that police sometimes had to control the crowds of patients.

Many people have praised her achievements. A Ghanaian doctor, Felix Konotey-Ahulu, wrote about her in 2005. He admired her ability to understand the social reasons behind diseases like kwashiorkor. He noted her respect for local traditions.

Another article recognized her for starting the field of specific medicine for mothers and children. In her early days, this work was often seen as "women's work." It was not considered "proper" modern medicine. She took many photos and notes in Ghana. She admired how local mothers cared for their babies. She noted that babies carried on their mothers' backs and breastfed often did "remarkably well." This was different from British parenting advice at the time. Her ideas became very important for future generations of doctors.

In 1983, Sally Craddock wrote a biography about her. It was called Retired, Except on Demand: The Life of Dr Cicely Williams. This title came from Dr. Williams' own words. Even after "officially retiring" at 71, she continued to travel and speak into her early 90s.

A 1986 book called Primary Health Care Pioneer: The Selected Works of Dr Cicely D. Williams said she achieved a "physician's dream." She diagnosed, investigated, and found a cure for a new disease. She did this in places without modern medical resources.

Death

Cicely Williams passed away in Oxford in 1992. She was 98 years old.

See also

In Spanish: Cicely Williams para niños

In Spanish: Cicely Williams para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |