Confederate Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Irish Catholic Confederation

Comhdháil Chaitliceach na hÉireann

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1642–1652 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Kilkenny | ||||||||

| Common languages | Irish, English | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Confederal constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

|

• 1641–1649

|

Charles I | ||||||||

|

• 1649–1653

|

Charles II | ||||||||

| Legislature | General Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | Irish Confederate Wars | ||||||||

| 1641 | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

1642 | ||||||||

| 1652 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

Confederate Ireland was a time when Irish Catholics governed themselves. This period lasted from 1642 to 1652. It happened during a big conflict called the Irish Confederate Wars, also known as the Eleven Years' War.

Catholic leaders, wealthy landowners, priests, and army commanders started the Confederation. They formed it after the Irish Rebellion of 1641. The Confederates controlled about two-thirds of Ireland from their main city, Kilkenny. Because of this, it was sometimes called the "Confederation of Kilkenny."

The Confederates included Catholics of both old Irish (Gaelic) and Anglo-Norman backgrounds. They wanted to end unfair treatment against Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland. They also wanted more self-rule for Ireland. Many also hoped to reverse the plantations of Ireland, which were settlements of Protestants on Irish land.

Most Confederates stayed loyal to Charles I of England. They believed they could make a lasting agreement with him. They hoped to get what they wanted by helping him defeat his enemies in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The Confederation had its own government, including a law-making body called the General Assembly. It also had a Supreme Council to run things and its own army. They even made their own coins, collected taxes, and had a printing press.

Confederate representatives were sent to and recognized by France, Spain, and the Papal States. These countries sent them money and weapons. The Confederate armies fought against different groups at various times. These included Royalists (supporters of the King), Parliamentarians (supporters of the English Parliament), and Scottish armies.

In 1647, the Confederates lost several important battles. This led them to make a deal with the Royalists. But this agreement caused arguments among the Confederates themselves. These arguments made it harder for them to fight off an invasion. In 1649, a large English army, led by Oliver Cromwell, invaded Ireland. By 1652, this army had defeated the Confederates and Royalists. Some Confederate soldiers continued fighting in small groups for another year.

Contents

How the Confederation Started

The Irish Catholic Confederation began after the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Its main goals were to control the rebellion and organize a Catholic army. This army would fight against the English and Scottish forces in Ireland. The Confederates hoped this would stop England or Scotland from taking over Ireland again.

A Catholic bishop, Nicholas French, and a lawyer, Nicholas Plunkett, started the idea for the Confederation. They presented their plans for a government to important Irish Catholic nobles. These nobles included Viscount Gormanston and Viscount Mountgarret. These nobles promised their own armies to the Confederation. They also convinced other rebels to join.

On March 17, 1642, these nobles signed a document called the "Catholic Remonstrance." It was sent to King Charles I. A few days later, on March 22, Catholic bishops met in Kells. Most of them declared that the rebellion was a "just war." This meant they believed it was right to fight.

On May 10, 1642, Catholic clergy from all over Ireland met in Kilkenny. Important church leaders were there, including archbishops and bishops. They wrote the Confederate Oath of Association. This oath asked all Catholics in Ireland to promise loyalty to Charles I of England. They also swore to follow the rules of the "Supreme Council of the Confederate Catholics." From then on, the rebels were called Confederates.

The meeting in Kilkenny also said the rebellion was a "just war" again. It called for a council in each Irish province. These would be watched over by a national council for all of Ireland. The leaders promised to punish any bad actions by Confederate soldiers. They also said they would remove any Catholic from the church who fought against the Confederation. The synod sent people to France, Spain, and Italy to get support, money, and weapons. They also wanted to recruit Irish soldiers serving in other armies. Lord Mountgarret was chosen as the president of the Supreme Council. A big meeting, called the General Assembly, was planned for October that year.

The First General Assembly

The first Confederate General Assembly met in Kilkenny on October 24, 1642. It set up a temporary government. This Assembly was like a parliament, even if it wasn't officially called one. Many important people were there. This included 14 nobles and 11 church leaders from the Parliament of Ireland. There were also 226 regular citizens. A lawyer from Galway, Patrick D'Arcy, wrote the Confederation's rules.

The Assembly decided that each county should have a council. These would be overseen by a provincial council. Each provincial council would have two representatives from each county council. The Assembly agreed on rules for how their government would work.

The Assembly also chose a group to run things, called the Supreme Council. The first Supreme Council was chosen around November 14. It had 24 members. Twelve of these members had to stay in Kilkenny or wherever the Council met.

The Supreme Council had power over all military generals, officers, and judges. Its first action was to name the generals for the Confederate armies. Owen Roe O'Neill led the Ulster forces. Thomas Preston led the Leinster forces. Garret Barry led the Munster forces. John Burke led the Connacht forces.

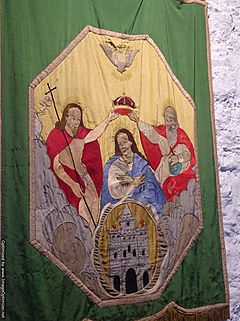

The Supreme Council also created its own official seal. This seal had a large cross, a flaming heart, and a dove. On the left was a harp, and on the right was a crown. The motto on the seal was Pro Deo, Rege, et Patria, Hiberni Unanimes. This means "For God, King and Fatherland, Ireland is United."

A National Treasury was set up in Kilkenny. They also created a mint to make coins and a press to print official announcements. This first General Assembly met until January 9, 1643.

What the Confederates Wanted

The English Parliament had passed a law in 1642 called the Adventurers' Act. This law would take land from "rebel" Irish Catholics to pay for the war. To keep their lands, the Confederates said they were loyal to King Charles I. This made it very important for them to reach an agreement with him.

Because of this, the Confederacy never said it was a fully independent government. Only the King could officially call a Parliament in Ireland. So, their General Assembly never claimed to be a true Parliament, even though it made laws.

The Confederates wanted several things. They wanted Ireland to govern itself. They wanted to keep their lands safely. They wanted to be forgiven for anything they did during the Rebellion. They also wanted an equal share in government jobs. They wanted these promises to be made official by a Parliament after the war.

For religion, they wanted Catholicism to be tolerated. By 1645, they also wanted Catholic clergy to keep all the church properties they had taken since 1641. But these demands were very hard to achieve. King Charles had refused similar things to the English Parliament. Also, most of his advisors were against these ideas. They thought it would hurt the King's cause in England and Scotland.

The Confederates' position was also weakened by disagreements among themselves. There were differences between the "Old English" (descendants of people who came in 1172) and the native "Gaelic Irish." While many historians debate how different they were, they had different goals. Generally, the Old English wanted to get back the power they had lost. They were Catholic but did not want Catholicism to be the official state religion. Gaelic Irish leaders, like Owen Roe O'Neill, wanted to reverse the Plantations of Ireland. This was the only way for them to get back their family lands.

The 1643 Truce

In September 1643, the Confederates made a "cessation" (a ceasefire) with James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde. Ormonde was the King's governor in Ireland. This agreement stopped fighting between the Confederates and Ormonde's Royalist army near Dublin.

However, not everyone agreed. Murrough O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin, a Protestant who led the Royalist army in Cork, did not like the ceasefire. He declared his loyalty to the English Parliament instead. Also, Scottish armies had landed in Ulster in 1642. They remained enemies of both the Confederates and the King.

In 1644, the Confederates sent about 1,500 soldiers to Scotland. These soldiers, led by Alasdair MacColla, helped the Royalists there fight against the Scottish Covenanters. This was the only time the Confederates directly helped the Royalists in the civil wars in Great Britain.

Help from the Pope

The Confederates received some money from the kings of France and Spain. These kings wanted to recruit Irish soldiers. But the most important support came from the Pope. Pope Urban VIII sent Pierfrancesco Scarampi to help the Confederates in 1643.

Later, Pope Innocent X strongly supported Confederate Ireland. He sent a special representative, Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, to Ireland in 1645. Rinuccini brought a lot of weapons, military supplies, and a large sum of money. This made Rinuccini very important in Confederate politics. He was supported by the more determined Confederates, like Owen Roe O'Neill.

When Rinuccini arrived in Kilkenny, he was welcomed with great honor. He said his goal was to support the King. But most importantly, he wanted to help Irish Catholics practice their religion freely. He also wanted to restore churches and church property to Catholic control.

The First Peace Deal with Ormonde

The Supreme Council hoped for a lot from a secret treaty they made with Edward Somerset, 2nd Marquess of Worcester. This treaty was made on behalf of the King. It promised more benefits for Irish Catholics in the future.

In 1646, the Supreme Council of the Confederates reached an agreement with Ormonde. This was signed on March 28, 1646. Under this deal, Catholics could hold public office and start schools. There were also spoken promises about religious tolerance later on. The agreement also offered forgiveness for actions during the 1641 Rebellion. It promised that no more land would be taken from Irish Catholic rebels.

However, this deal did not change Poynings' Law. This law meant that any new laws for the Parliament of Ireland had to be approved by the English government first. The deal also did not change the Protestant majority in the Irish House of Commons. It also did not reverse the main plantations in Ulster and Munster. Also, churches taken by Catholics during the war had to be given back to Protestants. The public practice of Catholicism was not fully guaranteed.

In return for these limited promises, Irish soldiers would be sent to England. They would fight for the Royalists in the English Civil War. However, the terms of this agreement were not accepted by the Catholic clergy. They were also rejected by Irish military commanders, especially Owen Roe O'Neill and Thomas Preston. Most of the General Assembly also disagreed.

The Papal Nuncio, Rinuccini, was not part of this treaty. It did not meet his goals. He convinced nine Irish bishops to sign a protest against any deal with Ormonde or the King. They wanted a guarantee that the Catholic religion would be fully supported.

Many believed the Supreme Council could not be trusted. Many of its members were related to Ormonde or connected to him. Also, people pointed out that the English Civil War was already being won by the English Parliament. Sending Irish troops to the Royalists seemed pointless. On the other hand, many felt that after O'Neill's army won the Battle of Benburb in June 1646, the Confederates could conquer all of Ireland. Those who opposed the peace deal were supported by Rinuccini. He even threatened to remove members of the "peace party" from the church. The Supreme Council members were arrested, and the General Assembly voted to reject the deal.

Military Defeats and a New Peace Deal

After the Confederates rejected the peace deal, Ormonde gave Dublin to an army from the English Parliament. This army was led by Michael Jones. The Confederates then tried to remove the remaining Parliamentarian forces in Dublin and Cork. But in 1647, they suffered several big military losses.

First, Thomas Preston's army was destroyed by Jones's Parliamentarians at the Battle of Dungan's Hill. Then, less than three months later, the Confederates' Munster army was defeated by Inchiquin's Parliamentarian forces at the Battle of Knocknanuss.

These defeats made most Confederates much more eager to make a deal with the Royalists. Negotiations started again. The Supreme Council received good terms from King Charles I and Ormonde. These included allowing the Catholic religion. They also promised to get rid of Poyning's Law, which would mean Irish self-government. The deal recognized lands taken by Irish Catholics during the war. It also promised to partly reverse the Plantation of Ulster. Plus, there would be an amnesty for all actions during the 1641 rebellion and the Confederate wars. This included the killings of British Protestant settlers in 1641. The Confederate armies would also not be disbanded.

However, King Charles only agreed to these terms because he was desperate. He later went back on his word. Under the agreement, the Confederation was supposed to break up. Its troops would be placed under Royalist commanders. English Royalist troops would also be accepted. Inchiquin also switched sides from Parliament and rejoined the Royalists in Ireland.

Disagreements Within the Confederation

Many Irish Catholics still refused to make a deal with the Royalists. Owen Roe O'Neill did not join the new Royalist alliance. He even fought a short civil war against the Royalists and Confederates in 1648. O'Neill was so upset by what he saw as a betrayal of Catholic goals that he tried to make a separate peace with the English Parliament. For a short time, he was actually an ally of the English Parliament's armies in Ireland.

This was very bad for the Confederation's overall goals. It happened at the same time as the start of the second civil war in England. The Papal Nuncio, Rinuccini, tried to support Owen Roe O'Neill. He even removed from the church those who made a truce with the Royalists in May 1648. But he could not get all the Irish Catholic Bishops to agree. On February 23, 1649, he left Galway to return to Rome.

People often say this split within the Confederates was between the Gaelic Irish and the Old English. It is suggested that the Gaelic Irish had lost more land and power. This made them want bigger changes. However, there were people from both groups on each side of the argument. For example, Phelim O'Neill, a Gaelic Irish leader, sided with the moderates. But the mostly Old English area of south Wexford rejected the peace. The Catholic clergy were also divided.

The real meaning of the split was between two groups. One group of landowners was willing to compromise with the Royalists. They just wanted their lands and civil rights guaranteed. The other group, like Owen Roe O'Neill, wanted to completely remove the English from Ireland. They wanted an independent, Catholic Ireland. They also wanted English and Scottish settlers to be permanently expelled. Many of these strong opponents wanted to get back the lands their families had lost in the plantations. After some small fights with the Confederates, Owen Roe O'Neill went back to Ulster. He did not rejoin his former friends until Cromwell's invasion in 1649. This internal fighting badly hurt the preparations of the Confederate-Royalist alliance to fight off the Parliamentarian army.

Cromwell's Invasion of Ireland

Oliver Cromwell invaded Ireland in 1649. His goal was to crush the new alliance of Irish Confederates and Royalists. The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland was the bloodiest war the country had ever seen. It also brought widespread disease and hunger. Kilkenny fell after a short siege in 1650. The war ended in a complete defeat for the Irish Catholics and Royalists.

Most of the Irish Catholic landowners from before the war were wiped out during this time. The Roman Catholic Church's organizations were also destroyed. Most of the top members of the Confederation went to live in France with the English Royalist Court. After the King returned to power in England, those Confederates who had supported the alliance with the Royalists were favored. On average, they got back about a third of their lands. However, those who stayed in Ireland during the time Cromwell ruled generally had their land taken away. Prisoners of war were either executed or sent to faraway colonies.

Why the Confederation Was Important

The Confederation of Ireland's way of governing was similar to the old Irish Parliament. This Parliament was set up by the Normans in 1297. But the Confederation's government was not based on people voting.

Even though they had a lot of potential power, the Confederates ultimately failed. They could not manage and reorganize Ireland to protect the interests of Irish Catholics. The Irish Confederate Wars and Cromwell's conquest (1649–53) caused huge loss of life. They ended with almost all Irish Catholic-owned land being taken away in the 1650s. Although some land was given back in the 1660s. This period firmly established English control over Ireland.

See also

- History of Ireland

- Early Modern Ireland 1536–1691

- Confederation