Normans in Ireland facts for kids

The Hiberno-Normans were a group of Normans who came to and settled in Gaelic Ireland starting in the 12th century. They were also called the Norman Irish. Most of them came from families in Wales (called Cambro-Normans) and England (called Anglo-Normans). These families were loyal to the Kingdom of England, and the English government supported their claims to land in Ireland.

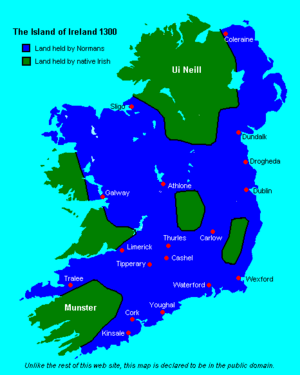

During the High Middle Ages and Late Middle Ages, the Hiberno-Normans became powerful feudal lords and rich merchants. They ruled a part of Ireland known as the Lordship of Ireland. The Normans were also important in changing the Catholic Church in Ireland. Over time, the descendants of these 12th-century settlers spread across Ireland and the world. Most of them stopped thinking of themselves as Norman or Anglo-Norman.

The power of the Norman Irish began to fade in the 16th century. This happened after new English Protestant settlers arrived during the Tudor period. Some of the Norman Irish, often called The Old English, had started to live like the native Gaels. They adopted Gaelic culture and married into Gaelic families. They became known as "Irish Catholics." However, some Hiberno-Normans joined the new English Protestant group and became known as the Anglo-Irish.

Some of the most well-known Norman families were the FitzMaurices, FitzGeralds, Burkes, Butlers, Fitzsimmons and Wall families. The common Irish surname Walsh comes from Normans who lived in Wales before coming to Ireland.

Contents

Who Were the "Old English"?

Historians sometimes disagree on the best way to describe the Normans in Ireland over time. They also debate how these groups saw themselves.

For example, the historian Edward MacLysaght separates "Hiberno-Norman" and "Anglo-Norman" surnames. This shows a difference between those who became more Irish and those who stayed loyal to England. The FitzGeralds of Desmond or the Burkes of Connacht, for instance, were very different from the Butlers of Ormond. The Butlers were much more connected to the Royal family.

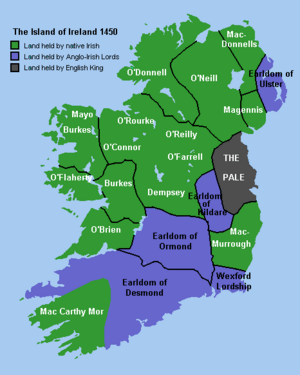

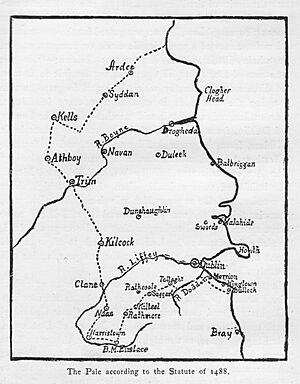

Some historians now use the term Cambro-Normans. This is because most Normans came to Ireland through Wales, not directly from England. But it seems strange to call their whole history "Old English," a term that only started being used in the late 1500s. Some say the "Old English" community really only formed in the late 16th century in a place called The Pale. Before that, their identity was more flexible. English policies actually helped create this distinct "Old English" group.

Brendan Bradshaw, another historian, noted that in the late 1500s, poets in Tír Chónaill didn't call Normans "Old Foreigners." Instead, they used terms like Fionnghaill and Dubhghaill (meaning "fair-haired foreigners" and "dark-haired foreigners," originally for Vikings). This was a way to show that these Norman families had been in Ireland for a long time. Bradshaw also believed that the term Éireannaigh (Irish people) began to be used during this time to unite both Gaels and Normans. He saw this as an early sign of Irish nationalism.

Interestingly, a study in 2011 found that Irish politicians elected between 1918 and 2011 often had different surnames based on their political party. Members of Fine Gael were more likely to have Norman surnames, while those from Fianna Fáil often had Gaelic surnames.

Why "Old English" vs. "New English"?

The name Old English (in Irish, Seanghaill, meaning "old foreigners") started being used by scholars after the mid-16th century. It described Norman descendants living in The Pale and Irish towns. These people increasingly opposed the Protestant "New English" who arrived in Ireland after the Tudor conquest of Ireland in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Many of the Old English lost their lands and power during the religious conflicts of the 16th and 17th centuries. This was mainly because they stayed loyal to the Roman Catholic religion. By 1700, those who remained Catholic tried to unite under the name "Irish Catholic." This was because both Norman and Gaelic Catholics were kept from wealth and power by the new English settlers, who became known as the Protestant Ascendancy.

The term "Old English" first appeared in the 1580s. Before then, people of Norman descent used other names for themselves, like "Englishmen born in Ireland." But it was during a tax crisis in the 1580s that a group calling itself the Old English community truly formed.

Norman History in Medieval Ireland

Historically, English governments in London expected the Normans in the Lordship of Ireland to support England's interests. This meant using the English language (even though they spoke Norman-French), English law, trade, money, customs, and farming methods. However, the Norman community in Ireland was never all the same.

In some areas, like around Dublin (called The Pale) and in towns like Kilkenny, Limerick, Cork, and south Wexford, people spoke English. They used English law and lived much like people in England.

But in other parts of Ireland, the Normans (called Gaill meaning "foreigners" in Irish) were often hard to tell apart from the surrounding Gaelic lords. Families like the Fitzgeralds, Butlers, Burkes, and Walls adopted the native language, legal system, and other customs. They fostered children with Gaelic families, married into them, and supported Irish poetry and music. These Normans became known as "more Irish than the Irish themselves."

The best name for this group during the late medieval period is Hiberno-Norman. This name shows the unique mix of cultures they created. To stop this mixing, the Irish Parliament passed the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1367. These laws banned using the Irish language, wearing Irish clothes, and even stopped Gaelic Irish people from living in walled towns.

The Pale and Its People

Despite these efforts, by 1515, an official complained that most common people in The Pale who followed the King's laws were "of Irish birth, of Irish habit, and of Irish language." English writers like Fynes Moryson in the late 1500s agreed. He said that the "English Irish" and even citizens (except in Dublin) usually spoke Irish among themselves. They were hard to convince to speak English. Another writer, Richard Stanihurst, noted in 1577 that Irish was "universally gaggled in the English Pale."

Outside the Pale, the term 'English' usually referred to a small group of landowners and nobles. They ruled over Gaelic Irish farmers and tenants. The border between the Pale and the rest of Ireland was not strict. Instead, there were gradual cultural and economic differences across wide areas.

So, the English identity that Pale representatives showed to the English Crown was often very different from their actual cultural ties to the Gaelic world. This difference between their real culture and their stated identity is a key reason why the Old English later supported Roman Catholicism.

Before the English Reformation in the 1530s, there was no religious division in medieval Ireland. However, after the Reformation, most people in Ireland who had lived there before the 16th century remained Catholic. This was true even after the Church of England and the Church of Ireland were set up.

Tudor Conquest and New English Settlers

Unlike earlier English settlers, the New English who came to Ireland from England during the Elizabethan era were more consciously English. Most of them were Protestant. To the New English, many of the Old English were "degenerate." This meant they had adopted Irish customs and stayed Catholic after the King broke away from Rome.

The poet Edmund Spenser strongly believed this. In his book A View on the Present State of Ireland (1595), he argued that England's failure to fully conquer Ireland in the past had made earlier English settlers "corrupted" by Irish culture. During the 16th century, this religious difference pushed the Old English away from the government. Eventually, it led them to join forces with the Gaelic Irish as Irish Roman Catholics.

The Cess Crisis

The first major conflict between the Old English and the English government in Ireland happened during the cess crisis from 1556 to 1583. During this time, the Pale community refused to pay for the English army sent to Ireland to stop a series of revolts, which ended with the Desmond Rebellions (1569–73 and 1579–83). The term "Old English" was created then. The Pale community stressed their English identity and loyalty to the Crown. But at the same time, they refused to cooperate with the English Crown's wishes, as represented by the Lord Deputy of Ireland.

At first, the conflict was about taxes. The Palesmen didn't want to pay new taxes that their own Parliament of Ireland hadn't approved. But the dispute soon became religious, especially after 1570. That year, Elizabeth I of England was excommunicated by Pope Pius V. In response, Elizabeth banned the Jesuits from her lands. They were seen as the Pope's most extreme agents of the Counter-Reformation, which aimed to remove her from power.

Rebels like James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald called their rebellion a "Holy War." They even received money and soldiers from the Pope. In the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), a leading Pale lord, James Eustace, Viscount of Baltinglass, joined the rebels for religious reasons. Before the rebellion ended, hundreds of Old English Palesmen were arrested and sentenced to death. Some were rebels, others were suspected because of their religious views. Most were later pardoned after paying large fines. However, twenty landed gentlemen from important Old English families were executed. Some of them "died like" Roman Catholic martyrs, saying they were suffering for their religious beliefs.

This event marked a big break between the Pale and the English government in Ireland, and between the Old English and the New English. In the later Nine Years' War (1594–1603), the Pale and the Old English towns remained loyal to the English Crown.

Rise of Protestantism

In the end, the English government's decision to organize its administration in Ireland along Protestant lines in the early 17th century broke the main political ties between the Old English and England. This was especially true after the Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

First, in 1609, Roman Catholics were banned from holding public office in Ireland. Then, in 1613, the way the Irish Parliament was set up changed. This gave the New English Anglicans a slight majority in the Irish House of Commons. Third, in the 1630s, many Old English landowners had to prove their old land titles. Often, they didn't have the right papers. This meant some had to pay large fines to keep their land, while others lost some or all of it in this complex legal process (see Plantations of Ireland).

The Old English community responded by appealing directly to the King of Ireland in England, bypassing his representatives in Dublin. This meant they had to appeal to their king in his role as King of England, which made them even more unhappy.

They asked first James I and then his son, Charles I, for a set of changes called The Graces. These included religious tolerance and equal rights for Roman Catholics in exchange for higher taxes. However, several times in the 1620s and 1630s, after they agreed to pay more taxes, the King or his Irish representative chose not to grant some of the promised changes.

This was bad for the English government in Ireland. It led Old English writers, like Geoffrey Keating, to argue that the true identity of the Old English was now Roman Catholic and Irish, not English. English policy thus sped up the blending of the Old English with the native Irish.

Loss of Land and Defeat

- Further information: Penal Laws

In 1641, many of the Old English made a big break with their past loyalty by joining the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Many things led to this decision. These included fear of the rebels and fear of the government punishing all Roman Catholics. But the main long-term reason was a desire to undo the anti-Roman Catholic policies of the English authorities over the past 40 years.

Even though they formed an Irish government in Confederate Ireland, the Old English identity was still a source of division among Irish Roman Catholics. During the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–53), the Gaelic Irish often accused the Old English of being too eager to sign a treaty with Charles I of England. They felt this was at the expense of Irish landowners and the Roman Catholic religion.

The following Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–53) led to the final defeat of the Roman Catholic cause. Most of the Old English nobility lost their lands. While this cause briefly returned before the Williamite war in Ireland (1689–91), by 1700, the Anglican descendants of the New English became the most powerful class in the country. This also included Old English families (and some Gaelic men) who chose to accept the new reality by joining the Established Church.

The Protestant Ascendancy

During the 18th century, under the Protestant Ascendancy, social groups were mostly defined by religion (Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Protestant Nonconformist), not by ethnic background. With the Penal Laws (Ireland) discriminating against both groups, and Ireland becoming more Anglicized, the old difference between Old English and Gaelic Irish Roman Catholics slowly disappeared.

Changing religion, or joining the State Church, was always an option for people in Ireland. It was a way to be included in the official "body politic." Many Old English, like Edmund Burke, became Anglicans but still understood the difficult situation of Roman Catholics. Others in the gentry, like the Viscounts Dillon and the Lords Dunsany, came from Old English families who had changed their religion to keep their lands and titles. Some members of the Old English who joined the Irish Ascendancy even supported Irish independence. For example, the Old English FitzGerald Dukes of Leinster held the top title in the Irish House of Lords. A member of that family, the Irish nationalist Lord Edward Fitzgerald, was the brother of the second duke.

Norman Surnames in Ireland

Here is a list of Hiberno-Norman surnames. Many of them are unique to Ireland. For example, the prefix "Fitz" means "son of," and it appears most often in Hiberno-Norman surnames. (It's like the modern French "fils de" with the same meaning). However, a few names with "Fitz-" sound Norman but are actually from Gaelic origins. For example, Fitzpatrick was a name taken by Brian Mac Giolla Phadraig when he submitted to Henry VIII in 1536.

- Barrett

- Bennett

- Blake, from de Blaca

- Blanchfield, from De Blancheville

- Bodkin

- Browne, from de Brún

- Bruce

- Burke, also Bourke, de Búrc, de Búrca and de Burge

- Butler

- Curtis

- D'Alton

- D'Arcy, also De Arcy

- de Barry

- de Cogan (now Goggin)

- de Clare

- Candon, Condon, from de Caunteton

- Cantillon

- Colbert

- Costello

- Cusack, also de Cussac (from Gascony, France)

- de Lacy

- Delaney

- Dillon, from de Leon

- Devereaux

- Deane, from de Denne

- de Troyes (now Troy)

- English

- Fagan

- Fanning

- Fay, from de Fae

- Finglas

- FitzGerald

- FitzGibbons

- Fitzhenry, also Fitzharris

- Fitzmaurice, also Fitzmorris

- FitzRalph

- Fitzrichard

- FitzRoy

- Fitzsimons/Fitzsimon

- Fitzstephen

- FitzWilliam

- French (de Freigne; de Freyne; ffrench - one of the 14 tribes of Galway)

- Gault (from Gualtier)

- Grace

- Hussey (From Houssaye in Normandy.) Also O'Hosey, Oswell

- Hand

- Harpur, De Harpúr (Irish), Le Harpur (Norman-French), Harpeare (Yola dialect), common in County Wexford.

- Hore (From William Le Hore in County Wexford.) Also Hoar or Hoare.

- Harris (From son of Harry)

- Joyce

- Jordan, Gaelic "Mac Siurtain"

- Kilcoyne, from the original Gaelic "O Cadhain", emerged in Norman Galway.

- Laughles (later Lawless)

- Lambart (Possible link between Lambarts and Lamberts)

- Lambert, also Lamport. Notably John Lambert of Creg Clare

- le Gros or later translation, "le Gras" (anglicized "Grace").

- Lovett, from Anglo-Norman French "lo(u)vet" meaning "wolf cub"

- Malet

- Mansell, from Le Mans, France

- Marmion

- Marren

- Martyn, also Martin

- Mansfield

- Mac Eoin Bissett

- Mee (Anglicized from Le Mée)

- Mohan (early descendant)

- Nagle

- Nangle

- Nicolas, Nicola

- Nugent

- Payne

- Peppard

- Perrin, Perrinne

- Petit, Petitt, Pettit

- Plunkett

- Power (le Poer)

- Prendergast

- Preston

- Purcell (meaning a swineherd, from Old French "pourcel" for piglet.)

- Redmond

- Roach (From Roche)

- Roche (From de Rupe or de la Roche)

- Rossiter (also Rosseter, Rossitur, Raucester, Rawcester, Rochester)

- Russell (From a French term for a red-haired person.)

- Sallenger, Sallinger, from St. Leger

- Savage

- Seagrave, Segrave

- Shortall

- Sinnott

- Stack

- Taaffe

- Talbot/Talbott

- Testard

- Tyrrell or Tyrell

- Troy (Anglicized from De Troye)

- Tobin

- Wall (Anglicized from Du Val). See Wall family in Ireland (1170-1970).

- Walshe/Walsh/Welsh (meaning "Welshman" or "Briton", from Gaelic Breathnach)

- de Warren, Warren

- Woulfe (Anglicized from the Original Norman-Gaelic De Bhulbh [Wolf])

- White/Whitty (Anglicized from the original de Faoite meaning "of fair skin")

Hiberno-Norman Writings

Old Irish records often separated Gaill (foreigners) from Sasanaigh (English). The Gaill were sometimes called Fionnghaill (fair foreigners) or Dubhghaill (dark foreigners), depending on how much the writer wanted to praise their patron.

There are many texts written in Hiberno-Norman French. Most of these are official documents, like business or legal papers. But there are also some stories and poems. A lot of parliamentary laws exist, including the famous Statutes of Kilkenny, as well as town documents.

The most important literary work is The Song of Dermot and the Earl. It's a long poem of 3,458 lines about Dermot McMurrough and Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (known as "Strongbow"). Other writings include Walling of New Ross from about 1275, and early 14th-century poems about the customs of Waterford.

Images for kids

-

In 1569 Sir Edmund Butler led a revolt after his lands were given to a "New English" settler, Sir Peter Carew.

See also

In Spanish: Hiberno-normando para niños

In Spanish: Hiberno-normando para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |