Plantations of Ireland facts for kids

The "Plantations" in Ireland during the 1500s and 1600s were a time when the English king or queen took land from Irish owners. This land was then given to new settlers from Great Britain. The English rulers wanted to control Ireland better. They also hoped to make the Irish more like the English and introduce their way of life.

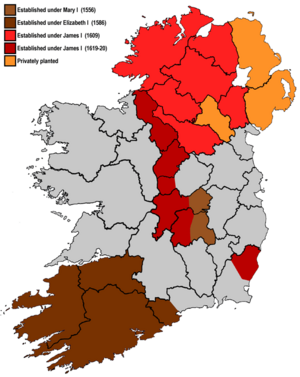

The biggest plantations happened between the 1550s and the 1620s. The largest one was the plantation of Ulster. These changes led to new towns being built. They also caused huge shifts in who owned land and how people lived. There were big changes in culture and the economy too. Sadly, the plantations also led to many years of fighting between different groups of people.

Small groups of people from Britain had moved to Ireland since the 1100s. This was after the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland. By the 1400s, English control was only in a small area called the Pale. In the 1540s, England started to conquer more of Ireland.

The first plantations began in the 1550s. This was when Queen Mary I ruled. These early plantations were in Laois (called 'Queen's County') and Offaly (called 'King's County'). They were set up around army forts. But they didn't work very well because Irish clans fought back strongly.

More plantations happened when Queen Elizabeth I was in charge. In 1568, there was an attempt to start a colony in Kerrycurrihy. But the Irish destroyed it. In the 1570s, a private group tried to plant settlers in east Ulster. This also caused fighting with local Irish leaders and failed.

The Munster plantation started in the 1580s. This happened after the Desmond Rebellions. Business people were asked to invest money in this plan. English settlers moved onto land taken from Irish rebel lords. But these settlements were spread out. Also, far fewer settlers came than expected. When the Nine Years' War began in the 1590s, most of these settlements were left empty. However, English settlers started to return after the war ended.

The plantation of Ulster began in the 1610s. This was when King James I ruled. After losing the Nine Years' War, many Irish lords from Ulster left Ireland. Their lands were then taken by the Crown. This was the biggest and most successful plantation. It covered most of the province of Ulster.

Ulster was mostly Irish-speaking and Catholic. But the new settlers had to be English-speaking Protestants. Most of them came from northern England and Scotland. This created a new group of people called the Ulster Protestant community.

The Ulster plantation was one reason for the 1641 Irish Rebellion. During this rebellion, thousands of settlers were killed, forced out, or fled. After the Irish Catholics were defeated in the Cromwellian conquest of 1652, most Catholic-owned land was taken. Thousands of English soldiers then settled in Ireland. More Scottish people also settled in Ulster, especially during a famine in Scotland in the 1690s. By the 1720s, British Protestants were the main group in Ulster.

The plantations changed the number of people in Ireland. They created large groups of people with British and Protestant backgrounds. These new ruling groups replaced the older Catholic ruling class. The older class had shared a common Irish identity with most people.

Contents

Early Plantations (1556–1576)

The first plantations in Ireland happened during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. The English government in Dublin wanted to make Irish areas peaceful. They also wanted to make them more English. They tried to get Irish leaders to accept English rule. If this didn't work, land was taken, and English settlements were started.

Laois and Offaly Plantations

The first big plantation of this kind was in 1556. It was in 'King's County' (now Offaly) and 'Queen's County' (now Laois). These names honored the new Catholic rulers, King Philip and Queen Mary I. The new main towns were named Philipstown (now Daingean) and Maryborough (now Portlaoise).

The local O'Moore and O'Connor clans often raided the English area around Dublin. So, the English leader, the Earl of Sussex, ordered that their land be taken. English settlers were meant to replace them. However, this plantation was not very successful. The O'Moores and O'Connors hid in the hills and bogs. They fought against the settlers for about 40 years.

In 1578, the English finally defeated the O'Moore clan. Many of their ruling families were killed at Mullaghmast in Laois. They had been invited there for peace talks. Rory Oge O'More, a rebel leader, was hunted down and killed later that year. Because of the ongoing fighting, it was hard to get people to settle in this new area. Settlements ended up being built mostly around army forts.

East Ulster Plantation

In the 1570s, there was an attempt to settle parts of east Ulster. This area had once been part of an English Earldom. This plan was called the "Enterprise of Ulster." In 1571, Queen Elizabeth gave Sir Thomas Smith a large part of Clannaboy and the Ards to colonize. Smith wanted younger sons of English gentlemen to lead the colony. Irish people would work as laborers.

In 1572, Smith's son landed in the Ards with 100 men. They were opposed by the local Irish lord, Brian McPhelim O'Neill. He said the land grant was illegal. The English often used Irish churches as army bases. So, McPhelim burned all the churches in the Ards to stop this. The settlers quickly built a fort near Comber. But the plantation failed after Smith's son was killed by Irishmen in 1573.

The plan was then taken over by Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex. He aimed to colonize much of County Antrim. He landed at Carrickfergus in 1573 with 1,100 men. But many died from a plague in the town. The settlers were opposed by McPhelim and other Irish leaders. In 1574, Essex's men killed many of McPhelim's group during a meeting at Belfast Castle. Essex then had McPhelim executed.

The MacDonnells, another Irish clan, called for help from their relatives in Scotland. In 1575, Essex sent his forces to attack the MacDonnells. This led to many MacDonnell men, women, and children being killed on Rathlin Island. By this time, Queen Elizabeth had stopped the plan. It was a failure that cost a lot of money for Essex and the Crown.

Munster Plantation (1583 onwards)

The Munster Plantation of the 1580s was the first large-scale plantation in Ireland. It was set up as a punishment for the Desmond Rebellions. The Geraldine Earl of Desmond had rebelled against English rule in Munster. After the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), the Desmond family was defeated. Their lands were taken by the Crown.

The English government decided to settle the province with colonists from England and Wales. They hoped these settlers would help prevent future rebellions. In 1584, a survey was done to give confiscated lands to English "Undertakers." These were wealthy colonists who promised to bring tenants from England to work their new lands. The Undertakers also had to build new towns and defend their areas.

However, the plan faced problems. There was less land available than thought. Also, lawsuits made things difficult. It was planned that 91 families would settle on 12,000 acres. Smaller grants were also planned. By 1611, it's thought that 94,000 acres originally given to Undertakers had been taken back. Out of 86 original volunteers, only 15 actually took land.

When the Nine Years' War broke out in 1598, one estimate said about 5,000 English settlers had come. But it's more commonly believed that the total English population was around 4,000. This was much less than the 11,375 people originally hoped for.

The Munster plantations also had a business side. Private individuals could buy land in Munster cheaply. Walter Raleigh owned large estates in Munster. He used the forests to make tobacco pipes and wine barrels. Other investors made a lot of money from the plantations. For example, Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, became very rich by buying Irish lands and developing them.

The confiscated lands were spread across modern counties like Limerick, Cork, Kerry, and Tipperary. But settlement was uneven. In some areas, land given to English Undertakers was taken back. This happened when native lords, like the MacCarthys, argued that their people had been wrongly removed.

The Munster Plantation was supposed to create strong, defendable settlements. But the English settlers were spread out in small groups. At first, English soldiers protected the Undertakers. But these soldiers were removed in the 1590s. So, when the Nine Years War reached Munster in 1598, most settlers were driven off their lands easily. They fled to walled towns or back to England. However, after the rebellion was put down in 1601–03, the Plantation was restarted. By the 1620s, the English settler population was much larger. They were strong enough to control a big area after the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

Ulster Plantation (1606 onwards)

Before its conquest in the Nine Years War (1594–1603), Ulster was the most Irish-Gaelic part of Ireland. It was the only province completely outside English control. The war ended with the surrender of the O'Neill and O'Donnell lords to the English Crown. But it was very expensive and difficult for the English.

When Hugh O'Neill and other rebel earls left Ireland in 1607, they hoped to get help from Spain for a new rebellion. The English leader, Arthur Chichester, saw this as a chance to colonize Ulster. He declared the lands of O'Neill, O'Donnell, and their followers to be taken by the Crown.

At first, Chichester planned a smaller plantation. It would include large grants to Irish lords who had helped the English during the war. But in 1608, Cahir O'Doherty's rebellion in County Donegal changed things. O'Doherty was a former English ally who felt he hadn't been rewarded fairly. The rebellion was quickly put down, and O'Doherty was killed. These events gave Chichester a reason to take all the land from the original landowners in Ulster.

In 1603, James VI of Scotland also became James I of England. This united the two crowns and gave him control of the Kingdom of Ireland. The Ulster Plantation was promoted as a joint "British" (English and Scottish) effort. The goal was to make Ulster peaceful and more like England. It was decided that at least half of the settlers would be Scots. Six counties were part of this official plantation:

The plan was shaped by two main ideas. First, the Crown wanted to protect the settlements from rebels. So, instead of settling planters in small, isolated areas, they took all the land. They then gave it out again, creating groups of British settlers around new towns and army bases. The new landowners were told not to take Irish tenants. They had to bring their farmers from England and Scotland. The remaining Irish landowners were given a quarter of the land in Ulster. The ordinary Irish people were to be moved to live near army bases and Protestant churches. The planters were not allowed to sell their land to any Irish person.

The second big influence on the Ulster plantation was the deals made among the British groups. The main landowners were English "Undertakers." These were rich men from England and Scotland who promised to bring tenants from their own estates. Planters were given about 3,000 acres each. They had to settle at least 48 adult men (including 20 families) who were English-speaking Protestants.

However, soldiers who had fought in Ireland (called "Servitors") also wanted land. They were led by Arthur Chichester. These former officers didn't have enough money to fund the colonization. So, their involvement was helped by the City of London (London's financial area). The city was given its own town, Derry, and lands. The Protestant Church of Ireland also received land. It was given all churches and lands that had belonged to the Roman Catholic church. The Crown wanted English church leaders to convert the Irish people to Protestantism.

The Ulster Plantation had mixed results for the English. By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male English and Scottish settlers in Ulster. This means the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000 to 150,000. They became the majority in areas like the Finn and Foyle valleys (around modern Derry and east County Donegal), north County Armagh, and east County Tyrone. The number of settlers grew quickly. Almost half of the migrants were women. This was a very high number compared to other colonies at the time.

But the Irish population was not removed or made English. In reality, settlers did not stay on poorer lands. They gathered around towns and the best land. This meant many English and Scottish landowners had to take Irish tenants. This went against the rules of the Ulster Plantation. In 1609, Chichester sent 1,300 former Irish soldiers from Ulster to serve in the Swedish Army.

Trying to convert the Irish to Protestantism also didn't work well. At first, the church leaders sent to Ireland only spoke English. But most native Irish people only spoke Irish Gaelic. Later, the Catholic Church worked hard to keep its followers among the native population.

Later Plantations (1610–1641)

Besides the Ulster plantation, several other smaller plantations happened. These were under the rule of the Stuart Kings—James I and his son Charles I—in the early 1600s. The first of these was in north county Wexford in 1610. Land was taken from the MacMurrough-Kavanagh clan.

Most land-owning families in Ireland had taken their estates by force over the past 400 years. So, very few of them had proper legal papers for their land. To get these papers, they had to give up a quarter of their lands. This rule was used against the Kavanaghs in Wexford. It was later used elsewhere to break up Catholic Irish estates, especially Gaelic ones. Following the example in Wexford, small plantations were started in Laois and Offaly, Longford, Leitrim, and north Tipperary.

In Laois and Offaly, the earlier Tudor plantation had been a series of army bases. In the more peaceful 1600s, it attracted many landowners, tenants, and workers. Important planters in Leinster during this time included Charles Coote and William Parsons.

In Munster, during the peaceful early 1600s, thousands more English and Welsh settlers arrived. Many small plantations happened in Munster then. Irish lords had to give up up to one-third of their estates to have their ownership recognized by the English. Settlers gathered in towns along the south coast. These included Youghal, Bandon, Kinsale, and Cork city. Famous English Undertakers of the Munster Plantation included Walter Raleigh and Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork. Boyle, especially, made a huge fortune by getting Irish lands and developing them for business and farming.

The Irish Catholic upper classes could not stop the plantations. They were not allowed to hold public office because of their religion. By 1615, they were a minority in the Irish Parliament. This was because "pocket boroughs" (areas where Protestants were the majority) were created in planted areas. In 1625, they got a temporary stop to land confiscations. They agreed to pay for England's war with France and Spain.

Besides the plantations, thousands of independent settlers came to Ireland in the early 1600s. They came from the Netherlands and France, as well as Britain. Many became chief tenants for Irish landowners. Others set up in towns, especially Dublin, often as bankers. By 1641, there were about 125,000 Protestant settlers in Ireland. But they were still outnumbered by native Catholics by about 15 to 1.

Not all early 1600s English Planters were Protestants. Many English Catholics settled in Ireland between 1603 and 1641. They came for economic reasons and to escape persecution in England. In England, Catholics were greatly outnumbered by Protestants. In Ireland, they could blend in with the local Catholic majority. English Catholic planters were most common in County Kilkenny. They may have made up half of all English and Scottish planters there.

Plantations became a big political issue again when Thomas Wentworth became Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1632. Wentworth's job was to raise money for King Charles I. He also wanted to strengthen the King's control over Ireland. This meant more plantations, both to make money and to reduce the power of Irish Catholic gentry.

Wentworth took land in Wicklow. He also planned a large Plantation of Connacht. In this plan, all Catholic landowners would lose between a half and a quarter of their estates. Local juries were forced to accept Wentworth's plan. When some Connacht landowners complained to Charles I, Wentworth had them imprisoned. However, settlements only happened in County Sligo and County Roscommon. Wentworth then looked at major Catholic landowners in Leinster for similar treatment. This included members of the powerful Butler family.

Wentworth's plans were stopped by the start of the Bishops Wars in Scotland. These wars eventually led to Wentworth's execution by the English Parliament. They also led to civil war in England and Ireland. Wentworth's constant questioning of Catholic land titles was a major cause of the 1641 Rebellion. It was also the main reason why Ireland's richest and most powerful Catholic families joined the rebellion.

The 1641 Rebellion

In October 1641, after a poor harvest and in a tense political situation, Phelim O'Neill started a rebellion. He hoped to fix problems for Irish Catholic landowners. But once the rebellion began, the anger of the native Irish in Ulster exploded. They started attacking settlers everywhere, especially in Ulster.

Writers at the time claimed over 100,000 Protestant victims. William Petty, in his survey of the 1650s, estimated about 30,000 deaths. More recent research, based on detailed records from Protestant refugees in 1642, suggests about 4,000 settlers were killed directly. Up to 12,000 more may have died from disease or hardship after being forced from their homes.

Ulster was hit hardest by the wars. Many civilians died, and many people were forced to move. The terrible acts committed by both sides made the relationship between settlers and native communities even worse. Even though peace eventually returned to Ulster, the wounds from the plantation and civil war years healed very slowly. Some argue they still affect Northern Ireland today.

In the 1641 Rebellion, the Munster Plantation was temporarily destroyed. This had also happened during the Nine Years' War. Ten years of fighting took place in Munster between the planters and their descendants, and the native Irish Catholics. But the differences between ethnic and religious groups were less clear in Munster than in Ulster. Some early English Planters in Munster had been Roman Catholics. Their descendants mostly sided with the Irish in the 1640s. On the other hand, some Irish noblemen who became Protestant, like Earl Inchiquin, sided with the settler community.

Cromwellian Land Changes (1652)

Over 12,000 soldiers from the New Model Army were given land in Ireland instead of their wages. The English government could not pay them. Many of these soldiers sold their land to other Protestants instead of settling in war-torn Ireland. But 7,500 soldiers did settle there. They had to keep their weapons to act as a backup army if there were future rebellions.

Along with "Merchant Adventurers" (people who invested in the colonization), probably over 10,000 Parliamentarians settled in Ireland after the civil wars. Most of these were single men. Many of them married Irish women, even though it was against the law. Some Cromwellian soldiers started to become part of Irish Catholic society. Also, thousands of Scottish soldiers, who had been in Ulster during the war, settled there permanently.

Some Parliamentarians had argued that all Irish people should be sent west of the River Shannon. They wanted to replace them with English settlers. But this would have needed hundreds of thousands of English settlers willing to come to Ireland, and such large numbers never arrived. Instead, a new class of British Protestant landowners was created in Ireland. They ruled over mostly Irish Catholic tenants.

A small number of the "Cromwellian" landowners were Parliamentarian soldiers or investors. Most were Protestant settlers who had been there before the war. They took the chance to get confiscated lands. Before the wars, Catholics owned 60% of the land in Ireland. During the time of the Commonwealth, Catholic landownership fell to 8–9%. After some land was given back in the Restoration period, it rose to 20% again.

In Ulster, the Cromwellian period removed the native landowners who had survived the Ulster plantation. In Munster and Leinster, most Catholic-owned land was taken after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. This meant English Protestants gained almost all the land for the first time in these areas. Also, under the Commonwealth, about 12,000 Irish people were sold into forced labor in the Caribbean and North American colonies. Another 34,000 Irish Catholics went to live in other countries, mostly Catholic ones like France or Spain.

Recent studies show that even though the native Irish land-owning class lost power, it never completely disappeared. Many found ways to work in trade or as main tenants on their families' old lands.

Later Settlement

For the rest of the 1600s, Irish Catholics tried to get the Cromwellian Act of Settlement changed. They briefly succeeded under James II during the Williamite war in Ireland. But the defeat of James II led to more land being taken.

In the 1680s and 1690s, another large wave of settlers came to Ireland. These new settlers were mainly Scots. Tens of thousands fled a famine in the lowlands and border regions of Scotland to come to Ulster. At this point, Protestants and people of Scottish descent (who were mostly Presbyterians) became the majority of the population in Ulster.

French Huguenots, who were Protestant, were also encouraged to settle in Ireland. They had been forced out of France after the King took back the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Many of these Frenchmen were former soldiers who had fought on the Williamite side in the war. This community settled mainly in Dublin. Some had already been merchants in London. The total number of people in this community may have reached 10,000.

Long-Term Results and Changes to Irish Culture

The Plantations had huge effects on Ireland. They led to the removal or execution of Catholic ruling families. These were replaced by what became known as the Protestant Ascendancy. These were Anglican landowners mostly from Great Britain. Their power was made stronger by the Penal Laws. These laws took away political rights and most land-owning rights from Catholics and other Protestant groups. They also brought harsh punishments for using the Irish language. And they limited Catholics' ability to practice their religion. The forced rule of the Protestant class in Irish life lasted until the late 1700s. They then reluctantly voted for the Act of Union with Britain in 1800. This law ended their parliament and made their government part of Britain's.

The plantations and the new farming methods also greatly changed Ireland's environment. In 1600, most of Ireland was covered in thick forests and was undeveloped. Most people lived in small, moving settlements. By 1700, Ireland's native forests were much smaller. They were cut down a lot and sold for profit by the settlers. This was for businesses like shipbuilding, as many English forests had been cut down too much. Some native animals, like the wolf, were hunted until they disappeared during this time. Most of the settler population lived in permanent towns or villages. Some Irish people continued their traditional ways and culture, but under strict control and punishments. By the end of the plantation period, almost all of Ireland was part of a market economy. But many poorer people had no access to money. They still paid rent with goods or services. The plantations also brought a new measurement system to Ireland, called the Irish measure.

See also

- British colonisation of the Americas

- Early Modern Ireland 1536-1691

- Protestant Ascendancy

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |