Reformation in Ireland facts for kids

The Reformation in Ireland was a big change in how people practiced religion and how churches were run in Ireland. It was started by the English government because of King Henry VIII of England. He wanted to end his marriage, which was called the King's Great Matter. But Pope Clement VII said no. So, to get what he wanted, King Henry decided he needed to be in charge of the Catholic Church in his own country.

In 1534, the English Parliament passed laws called the Acts of Supremacy. These laws said the King was the boss of the Church in England. This meant he broke away from the Pope's power. By 1541, the Irish Parliament also agreed to this change. Ireland went from being a Lordship (ruled by a Lord) to a Kingdom with a King.

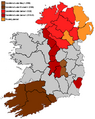

Unlike other religious changes in Europe, the Reformation in Ireland was mostly driven by what the government wanted. In England, people slowly got used to these changes. But in Ireland, most people did not agree with the government's new rules. They continued to be Catholic.

Contents

King Henry VIII's Religious Changes

English kings had called themselves "Lord of Ireland" since the Norman invasion of Ireland. But in 1542, the Irish Parliament gave King Henry a new title: King of Ireland. This changed Ireland into the Kingdom of Ireland. The King wanted this new title because the Pope had originally given him the title of "Lord of Ireland." Henry worried that the Pope, who had kicked him out of the Church in 1533 and 1538, could take away his title.

Henry also made the Irish Parliament declare him the head of the "Church in Ireland." The main person who helped set up this new state church was George Brown, the Archbishop of Dublin. The King chose him without the Pope's approval. Archbishop Brown arrived in Ireland in 1536. King Henry's son, Edward VI of England, continued these changes. The Church of Ireland says it has a direct link to the early Christian leaders, but the Catholic Church disagrees.

King Henry treated people who spoke out against him differently. Catholics who stayed loyal to the Pope were seen as traitors. Lutherans, who were very rare in Ireland, were seen as heretics and could be burned to death. In 1539, he passed a law called the Six Articles Act.

Henry died in 1547. During his rule, church prayers stayed the same, using Latin. But in 1549, the Book of Common Prayer was introduced in English. Also, from 1548, for the first time, Irish churchgoers were given both wine and bread during the Eucharist. Before, only the priest drank the wine.

Closing Down Monasteries

In Ireland, closing down monasteries happened differently than in England. Around 1530, Ireland had about 400 religious houses. This was a lot compared to its size and wealth. Unlike in England, friaries (houses for friars) in Ireland were doing very well in the 1400s. They had a lot of public support and money, built many new buildings, and kept up their religious life. They made up about half of all religious houses.

However, Irish monasteries had seen a big drop in numbers. By the 1500s, only a few still followed daily religious practices. King Henry's direct power only reached the area around Dublin called the Pale. From the late 1530s, his officials tried to convince some local chiefs to agree to his policies, including accepting his new state religion.

Still, Henry was determined to close down monasteries in Ireland. In 1537, he introduced a law in the Irish Parliament to make it legal. But there was a lot of resistance, and only sixteen houses were closed. Henry kept pushing, and from 1541, as part of the Tudor conquest of Ireland, he tried to close more. Most of the time, this meant making deals with local lords. Monastic lands were given away in exchange for promises of loyalty to the new Irish Crown. Because of this, Henry didn't get much money from the Irish monasteries.

By the time Henry died in 1547, about half of the Irish monasteries had been closed. But many friaries kept fighting against being closed down, even into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Church Lands and Property

During the English Reformation, the Church of Ireland lost a lot of its property. Much of the church's land and wealth ended up in the hands of powerful people. Many Irish bishoprics (areas managed by bishops) never got back what they lost. Some became almost worthless.

King Edward VI's Religious Changes

King Henry's son, Edward VI of England, ruled from 1547 to 1553. He officially made Protestantism the state religion. For Edward, this was more about religion itself, while for his father, it was more about politics. Edward ruled for only six years. His main change, the Act of Uniformity 1549, didn't have as much effect in Ireland as it did in England. He also ended the crime of heresy in 1547.

During his rule, people tried to bring Protestant church services and bishops to Ireland. But these efforts were met with strong dislike from within the Church, even from those who had agreed to earlier changes. In 1551, a printing press was set up in Dublin. It printed a Book of Common Prayer in English.

Queen Mary I's Religious Changes

King Henry's and Edward's changes were undone by Queen Mary I of England, who ruled from 1553 to 1558. She was always Catholic. When she became queen, Mary brought back traditional Roman Catholicism with new laws in 1553 and 1555. When some bishop positions in Ireland became empty, Mary chose Catholic priests who were loyal to Rome, with the Pope's approval. In other cases, bishops who had been chosen by her father without the Pope's approval were removed.

She also made sure the Act of Supremacy (which said England was independent from the Pope) was cancelled in 1554. She also brought back laws against heresy. It was agreed that the former monasteries would stay closed. This was to keep the loyalty of those who had bought the monastery lands. This agreement was made in January 1555 with Pope Julius III. In Ireland, Mary started the first planned settlements of English people. It's interesting that these settlements later became linked with Protestantism.

In 1554, Mary married Philip, who became King of Spain in 1558. In 1555, Pope Paul IV also gave Philip and Mary a special order to confirm their status as the Catholic King and Queen of the new Kingdom of Ireland.

Also in 1555, the Peace of Augsburg established a rule: "Cuius regio, eius religio" (whose realm, his religion). This meant Christians had to follow their ruler's religion. It seemed like the idea of the Reformation had ended.

Queen Elizabeth I's Religious Changes

Mary's Protestant half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I, became queen. In 1559, she made the Parliament pass another Act of Supremacy. This law said the English crown was the "only supreme head on earth of the Church in England" instead of the Pope. Any act of loyalty to the Pope was seen as treason because the Pope claimed both religious and political power.

Also, the Irish Act of Uniformity, passed in 1560, made it mandatory to worship in churches that followed the Church of Ireland. Anyone who took a job in the Irish church or government had to take the Oath of Supremacy. If they broke this oath, they could face severe punishments. Attending Church of Ireland services became required. Those who refused, whether Catholics or other Protestants, could be fined and physically punished as recusants (people who refused to attend Anglican services).

At first, Elizabeth tolerated people who didn't follow the Anglican church. But after the Pope issued a special order called Regnans in Excelsis in 1570, Catholics were increasingly seen as a danger to the country. Still, enforcing these rules in Ireland was not always strict for much of the 1500s.

Religious and political rivalry continued during two big rebellions: the Desmond Rebellions (1569–83) and the Nine Years' War (1594–1603). These wars happened at the same time as the Anglo-Spanish War. During this time, some rebellious Irish nobles got help from the Pope and from Elizabeth's enemy, Philip II of Spain. Because the country was so unsettled, Protestantism didn't spread much in Ireland, unlike in Scotland and Wales. It became linked with military conquest and settlement, so many people hated it. Important figures like Adam Loftus were both Archbishop and Lord Chancellor of Ireland, showing how religion and politics were mixed.

Most Protestants in Ireland during Elizabeth's rule were new settlers and government officials. They were a small group. Among the native Gaelic Irish and the Old English (descendants of earlier English settlers), most remained Catholic. Elizabeth often tolerated this because she didn't want to make the Old English even more upset. To them, the official state religion had already changed several times since 1533, and they thought it might change again. This was especially true because Elizabeth's heir until 1587 was the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots.

Elizabeth started Trinity College Dublin in 1592. One reason was to train clergy to preach the new Protestant faith. In 1571, a special printing type for the Irish language was created and brought to Ireland. It was used to print documents in Irish to help spread the new religion. The first translation of the New Testament into Irish was finished in 1603.

King James I's Religious Changes

The rule of King James I (1603–25) started with more tolerance. A peace treaty was signed with Spain in 1604. But the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 (a plan to blow up Parliament) made him and his officials take a tougher stance against Catholics. Catholics were still the majority, even in the Irish House of Lords. So few people had converted to Protestantism that the Catholic Counter-Reformation (a movement to strengthen Catholicism) was introduced in Ireland in 1612, much later than in the rest of Europe.

The Flight of the Earls in 1607 led to the Plantation of Ulster. Many of the new settlers there were Presbyterian (another type of Protestant) and not Anglican. They were reformed, but not fully accepted by the Dublin government. These settlers helped James create a small Protestant majority in the Irish House of Commons in 1613.

The first translation of the Old Testament into Irish was done by William Bedell (1573–1642), who was the Bishop of Kilmore. He finished his translation during the reign of King Charles I, but it wasn't published until 1680. Bedell had also translated the Book of Common Prayer in 1606.

In 1631, the Primate (a high-ranking bishop) James Ussher wrote a book arguing that the earlier forms of Irish Christianity were independent and not controlled by the Pope. Ussher is also famous for calculating from the Bible that the Earth was created on October 22, 4004 BCE.

Later Policies: Commonwealth and Restoration

The final stage of this period was the Irish Rebellion of 1641. This was a rebellion by Irish nobles who were loyal to the King, Catholicism, or both. The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland from 1649–53 briefly made Puritanism the state religion. The period after that, called the Restoration, and the short rule of the Catholic King James II, were known for unusual state tolerance for different religions. During the Patriot Parliament of 1689, King James II, even though he was Catholic, refused to give up his position as head of the Church of Ireland. This made sure that Protestant bishops attended the Parliament meetings.

In the Williamite War in Ireland that followed, absolute rule by kings was ended. But most of the Irish population felt more conquered than ever. The Irish Parliament then introduced a series of "Penal Laws." These laws were meant to reduce the power of Catholicism. However, there wasn't a strong effort to actively convert most people to Anglicanism. This suggests that the main goals of the Protestant Ascendancy (the ruling Protestant class) were economic: to transfer wealth from Catholic hands to Protestant hands, and to encourage Catholic property owners to become Protestant.

An Irish translation of the revised Book of Common Prayer from 1662 was done by John Richardson (1664–1747) and published in 1712.

Despite the Reformation being linked with military conquest, Ireland produced important Anglican Irish thinkers and writers. Some were Church of Ireland clergy, like James Ussher, Archbishop of Dublin; Jonathan Swift, a priest; John Toland, an essayist and philosopher; and George Berkeley, a bishop. The Presbyterian philosopher Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) had a big impact in Colonial America.

See also

- Second Reformation

- History of Ireland (1536–1691)

- Protestant Ascendancy

- Protestantism in Ireland

Images for kids

-

Quin Abbey, a Franciscan friary built in the 15th century and closed in 1541

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |