John Toland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Toland

|

|

|---|---|

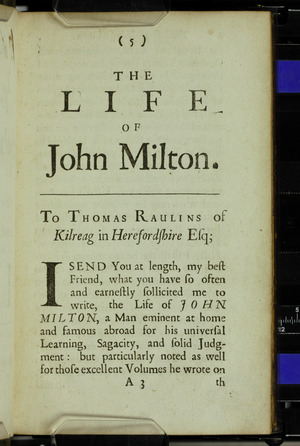

The only known image of Toland

|

|

| Born | 30 November 1670 Ardagh, County Donegal, Ireland

|

| Died | 11 March 1722 (aged 51) London, Great Britain

|

| Other names | Janus Junius Toland, Seán Ó Tuathaláin, Eoghan na leabhar (John of the books) |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

|

Main interests

|

Liberty, theology, physics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Pantheism |

|

Influences

|

|

John Toland (born November 30, 1670 – died March 11, 1722) was an Irish thinker. He believed in using reason to understand the world. He was also a freethinker, meaning he questioned traditional beliefs. Toland wrote many books about political philosophy and religion. His ideas were important in the early Age of Enlightenment, a time when people started to think more about reason and individual rights.

Toland was born in Ireland. He studied at several universities, including Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leiden, and Oxford. He was inspired by the ideas of another famous philosopher, John Locke.

His most famous book was Christianity Not Mysterious, published in 1696. In this book, he argued against strict rules in both the church and the government. His ideas were so controversial in Ireland that copies of his book were publicly burned. He had to leave the country and never returned.

Contents

John Toland's Early Life and Education

Not much is known about John Toland's very early life. He was born in a place called Ardagh. This area in northwestern Ireland was mostly Catholic and spoke Irish. We don't know who his parents were.

Toland later wrote that he was baptized Janus Junius. This was a clever play on his name. It reminded people of the Roman god Janus, who had two faces. It also brought to mind Lucius Junius Brutus, a famous founder of the Roman Republic. When he was a schoolboy, his teacher encouraged him to use the name John.

Becoming a Protestant and Studying at Universities

When he was 16, Toland officially changed from being Catholic to Protestant. He then received a scholarship to study theology at the University of Glasgow. In 1690, at just 19 years old, he earned a master's degree from the University of Edinburgh.

After that, he got another scholarship. This allowed him to study for two years at University of Leiden in Holland. He then spent almost two years at Oxford in England (1694–1695). At Oxford, he became known for being very smart. However, some people thought he didn't have much religious faith. The scholarship for Leiden came from wealthy English Protestants. They hoped Toland would become a minister for their church.

Controversial Ideas and Later Life

John Toland's first book was Christianity not Mysterious (1696). He started writing it while he was at Oxford. In this book, he said that the Bible's divine messages don't contain real mysteries. He believed that all religious ideas could be understood using human reason. He thought that trained minds could figure out all the teachings of faith.

His arguments quickly caused a lot of debate. Many people wrote responses to his book. In London, a grand jury even started a legal case against him. Since he was from Ireland, some members of the Parliament of Ireland wanted him to be burned at the stake. He had to leave Ireland in 1697. In his absence, three copies of his book were burned by the public hangman in Dublin. This was because the book's ideas went against the main beliefs of the Church of Ireland. Toland was very upset by this. He compared the Protestant lawmakers to "Popish Inquisitors." These were people who punished books when they couldn't catch the author.

After leaving Oxford, Toland lived mostly in London for the rest of his life. But he also traveled often to other parts of Europe, especially Germany and the Netherlands. He lived on the European continent from 1707 to 1710. Toland passed away in Putney, London, on March 10, 1722. He was 51 years old. The Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) said he died "in great poverty, in the midst of his books, with his pen in his hand."

Just before he died, Toland wrote his own epitaph. Part of it says: "He was an assertor of liberty, a lover of all sorts of learning... but no man's follower or dependent. Nor could frowns or fortune bend him to decline from the ways he had chosen." This means he believed in freedom and loved learning. He didn't follow anyone else's ideas and stayed true to his own path. He also wrote biographies during his life. His epitaph ends by saying: "If you would know more of him, search his writings."

Soon after Toland's death, a long biography about him was written by Pierre des Maizeaux.

John Toland's Political Views

John Toland was the first person to be called a freethinker. This name was given to him by Bishop Berkeley. Toland wrote over a hundred books on many topics. Most of them criticized church organizations and their power. A lot of his work focused on writing political essays. He supported the Whig cause, which favored more individual freedoms.

Many scholars know him for his role as a biographer or editor. He worked on writings by important thinkers from the mid-1600s. These included James Harrington, Algernon Sidney, and John Milton. His books Anglia Libera and State Anatomy showed his support for a type of English government. This government combined republican ideas with a king or queen who followed a constitution. In 1701, he visited Hanover. There, he was welcomed by the electress Sophia. This was because Anglia Libera supported the idea of the Hanover family becoming the next rulers of Britain.

After Christianity Not Mysterious, Toland's ideas became even more radical. He was against strict rules in the church. This led him to also oppose strict rules in the government. He believed that bishops and kings were equally problematic. He also thought that monarchy did not have a God-given right to rule. In his 1704 book Letters to Serena, he used the word "pantheism". He carefully looked at how people find truth. He also explored why people often believe in "false consciousness," or wrong ideas.

Liberty and Equality for All Citizens

In politics, Toland's most radical idea was that liberty is a key part of being human. He believed that political systems should be designed to guarantee freedom. Their purpose should not just be to create order. For Toland, reason and tolerance were the two main supports of a good society. This was a very advanced idea for the Whig party. It was the opposite of the Tory belief in sacred authority for both the church and the state.

Toland believed that all free-born citizens should be perfectly equal. He even extended this idea to the Jewish community. In early 18th-century England, Jewish people were tolerated but still seen as outsiders. In his 1714 book Reasons for Naturalising the Jews, he was the first to argue for full citizenship and equal rights for Jewish people.

Toland's world wasn't just about calm thinking. He also wrote fiery political pamphlets. Sometimes, he would use strong anti-Catholic feelings of the time. He used these feelings in his attacks on the Jacobites, who supported the Catholic royal family.

The Rumored "Treatise of the Three Impostors"

Toland was also involved in some very controversial writings. There were rumors about a book called the Treatise of the Three Impostors. This book supposedly said that Christianity, Judaism, and Islam were all big political tricks. People had heard rumors about this book existing since the Middle Ages. It was talked about all over Europe. Today, most people think the book never actually existed.

Toland claimed to have his own copy of this rumored book. He said he gave it to a group of thinkers in France led by Jean Rousset. Some people took seriously the rumors that it was then translated into French. However, Voltaire, another famous writer, did not believe it. He wrote a funny, sarcastic reply to the rumors.

Editing Works of Republican Thinkers

Toland showed his support for a republican style of government. He did this by editing the writings of important thinkers from the 1650s. These included James Harrington, Algernon Sydney, Edmund Ludlow, and John Milton.

When he supported the Hanover family as the next rulers, he made his republican ideas a bit less extreme. Still, his perfect king would work to create good citizens and social harmony. This king would also ensure "just liberty" and help people improve their reason. But George I and the powerful group around Robert Walpole were very different from Toland's ideal.

John Toland's Religious Views

Toland's book Christianity not Mysterious was similar in title and ideas to John Locke's 1695 book Reasonableness of Christianity. Because of this, Locke quickly said that their ideas were not the same. This led to a debate between Edward Stillingfleet and Locke.

Toland's next important work was the Life of Milton (1698). In it, he mentioned "numerous fake writings under the name of Christ and His apostles." This led to accusations that he was questioning the truthfulness of the New Testament writings. Toland replied in his book Amyntor, or a Defence of Milton's Life (1699). In this book, he included a notable list of what are now called New Testament apocrypha. These are writings that were not included in the official Bible. In his comments, he really started a big discussion about the history of the Biblical canon, which is the list of books accepted as part of the Bible.

In 1705, Toland called himself a pantheist in his publication Socinianism Truly Stated, by a pantheist. When he wrote Christianity not Mysterious, he was careful to show he was different from both non-believers and strict religious leaders. He created a stricter version of Locke's ideas about how we gain knowledge. Toland then went on to show that no facts or teachings from the Bible are unclear or unreasonable. He believed they were neither against reason nor too hard to understand. He thought all religious messages were human messages. Anything that couldn't be understood should be rejected as nonsense.

After Christianity not Mysterious, Toland's "Letters to Serena" became his most important contribution to philosophy. In the first three letters, he explained how superstition grew over time. He argued that human reason can never fully free itself from old beliefs. In the last two letters, he developed a new idea about materialism. This idea was based on criticizing the idea of a single substance. Later, Toland continued to criticize church government in Nazarenus. This idea was first fully developed in his "Primitive Constitution of the Christian Church," a secret writing circulated around 1705. The first part of "Nazarenus" highlighted the right of the Ebionites to have a place in the early church. His main point was to push the limits of how much official religious rules could be based on the Bible. Later important works include Tetradymus, which contains Clidophorus. This was a historical study of the difference between public (exoteric) and secret (esoteric) philosophies.

His book Pantheisticon, sive formula celebrandae sodalitatis socraticae (Pantheisticon, or the Form of Celebrating the Socratic Society) caused great offense. He printed only a few copies for private use. It was like a church service made up of passages from ancient non-Christian writers. It copied the style of the Church of England worship. The title itself was alarming back then. Even more so was the mystery Toland created around whether such groups of pantheists actually existed. Toland used the term "pantheism" to describe the philosophy of Spinoza.

Toland was known for separating exoteric philosophy from esoteric philosophy. Exoteric philosophy was what one said publicly about religion. Esoteric philosophy was what one shared only with trusted friends. In 2007, Fouke's book Philosophy and Theology in a Burlesque Mode: John Toland and the Way of Paradox analyzed Toland's "exoteric strategy." This was his way of speaking like others but with a different meaning. Fouke argued that Toland's philosophy and theology were not about directly stating his beliefs. Instead, his goal was to join in discussions while secretly questioning them from within. Fouke traced Toland's methods to Shaftesbury's idea of a funny or "mocking" way of philosophizing. This was meant to expose overly academic ideas, fakes, strict beliefs, and foolishness.

John Toland's Influence and Legacy

John Toland was a person ahead of his time. He believed in principles of virtue and duty. These ideas were not very popular in England during the time of Robert Walpole. That era was more about being cynical and self-interested.

Also, his intellectual fame was later overshadowed by thinkers like John Locke and David Hume. Even more so, it was overshadowed by Montesquieu and the French radical thinkers. Edmund Burke wrote about Toland and his friends in his book Reflections on the Revolution in France. Burke dismissed them, saying: "Who, born within the last 40 years, has read one word of Collins, and Toland, and Tindal, and Chubb, and Morgan, and that whole race who called themselves Freethinkers?"

Still, in Christianity not Mysterious, his most famous book, Toland challenged authority. He questioned not just the power of the established church. He also questioned all old and unquestioned authority. So, his book was radical in politics, philosophy, and religion.

Professor Robert Pattison wrote about Toland's influence: "Two centuries earlier the establishment would have burned him as a heretic. Two centuries later it would have made him a professor of comparative religion in a California university. In the rational Protestant climate of early 18th-century Britain, he was merely ignored to death."

However, Toland did find some success after his death. Thomas Hollis, a famous book collector and editor from the 1700s, asked a London bookseller named Andrew Millar to publish books that supported republican government. This list of books, published in 1760, included Toland's work.

John Toland's Writings

Here is a list of some of John Toland's important works:

- Christianity Not Mysterious: A Treatise Shewing, That there is nothing in the Gospel Contrary to Reason, Nor Above It: And that no Christian Doctrine can be properly called A Mystery (1696)

- A Discourse on Coins, by Seignor Bernardo Davanzati, anno 1588, translated out of Italian by John Toland (1696). (Note: Issues with money, like coin clipping, were a big public concern around 1696).

- An Apology for Mr. Toland (1697) (This was about Toland's earlier book Christianity Not Mysterious).

- An Argument Shewing, that a Standing Army Is Inconsistent with a Free Government, and absolutely destructive to the Constitution of the English Monarchy (1697)

- The Militia Reformed: An easy scheme of furnishing England with a constant land force, capable to prevent or to subdue any foreign power, and to maintain perpetual quite at home, without endangering the public liberty. (1698). (Note: The question of having a national army was a big topic for the British public around 1698).

- The Life of John Milton, containing, besides the history of his works, several extraordinary characters of men, of books, sects, parties and opinions. (1698)

- Amyntor, or a Defence of Milton's Life [meaning Toland's earlier book] Containing (I) a general apology for all writings of that kind, (II) a catalogue of books attributed in the primitive times to Jesus Christ, his apostles and other eminent persons, with several important remarks relating to the canon of Scripture, (III) a complete history of the book Eikon Basilike proving Dr Gauden and not King Charles I to be the author of it. (1699).

- Edited James Harrington's Oceana and other Works (1700)

- The Art of Governing by Parties, particularly in Religion, Politics, Parliament, the Bench, and the Ministry; with the ill effects of Parties. (1701).

- Anglia Libera; or the limitation and succession of the crown of England explained and asserted. (1701).

- Limitations for the next Foreign Successor, or A New Saxon Race: Debated in a Conference betwixt Two Gentlemen; Sent in a Letter to a member of parliament (1701)

- Propositions for Uniting the Two East India Companies (1701)

- Paradoxes of State, relating to the present juncture of affairs in England and the rest of Europe, chiefly grounded on his Majesty's princely, pious and most gracious speech [referring to a recent speech by the king of England]. (1702).

- Reasons for inviting the Hanover royals into England.... Together with arguments for making a vigorous war against France. (1702).

- Vindicius Liberius. (1702). (This was another defense of Christianity Not Mysterious, against a specific attack).

- Letters to Serena (1704)

- Hypatia or the History of a most beautiful, most virtuous, most learned and in every way accomplished lady, who was torn to pieces by the clergy of Alexandria to gratify the pride, emulation and cruelty of the archbishop commonly but undeservedly titled St Cyril (1720)

- The Primitive Constitution of the Christian Church (around 1705; published after his death, 1726)

- The Account of the Courts of Prussia and Hanover (1705)

- Socinianism Truly Stated (by "A Pantheist") (1705)

- Translated Matthäus Schiner's A Philippick Oration to Incite the English Against the French (1707)

- Adeisidaemon – or the "Man Without Superstition" (1709)

- Origines Judaicae (1709)

- The Art of Restoring (1710)

- The Jacobitism, Perjury, and Popery of High-Church Priests (1710)

- An Appeal to Honest People against Wicked Priests (1713)

- Dunkirk or Dover (1713)

- The Art of Restoring (1714) (against Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer|Robert Harley)

- Reasons for Naturalising the Jews in Great Britain and Ireland on the same foot with all Other Nations (1714)

- State Anatomy of Great Britain (1717)

- The Second Part of the State Anatomy (1717)

- Nazarenus: or Jewish, Gentile and Mahometan Christianity, containing the history of the ancient gospel of Barnabas... Also the Original Plan of Christianity explained in the history of the Nazarens.... with... a summary of ancient Irish Christianity... (1718)

- The Probability of the Speedy and Final Destruction of the Pope (1718)

- Tetradymus (1720) (Written in Latin. An English translation was published in 1751)

- Pantheisticon (1720) (Written in Latin. An English translation was published in 1751)

- History of the Celtic Religion and Learning Containing an Account of the Druids (1726)

- A Collection of Several Pieces of Mr John Toland, edited by P. Des Maizeaux, 2 volumes (1726)

See also

In Spanish: John Toland para niños

In Spanish: John Toland para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |