Williamite War in Ireland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Williamite War in Ireland |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Glorious Revolution | |||||||

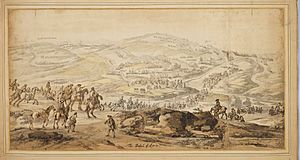

Battle of the Boyne between James II and William III, 11 July 1690, Jan van Huchtenburg |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 44,000 | 36,000–39,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,000 killed or died of disease | 15,293 killed or died of disease, incl. 2,000 irregulars | ||||||

The Williamite War in Ireland (also known as "war of the two kings") was a big conflict that happened in Ireland from March 1689 to October 1691. It was fought between two groups: those who supported King James II and those who supported his replacement, William III. In the end, William's side won. This war was also connected to a larger European conflict called the Nine Years' War.

In 1688, a major event called the Glorious Revolution happened in England. This led to the Catholic King James being replaced by his Protestant daughter Mary II and her husband William. They became joint rulers of England, Ireland, and Scotland.

King James still had many supporters in Ireland, especially among the mostly Catholic population. These supporters, called Jacobites, hoped James would help them with problems like land ownership, religious freedom, and basic rights. Most Irish Protestants fought for William, but some Protestants also supported James.

The war started in March 1689 with small fights. James's Irish Army had stayed loyal to him. They fought against Protestant groups who supported William. A key moment was the siege of Derry, where the Jacobites failed to capture an important northern town. This allowed William to send his own army to Ireland.

William's army defeated the main Jacobite army at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690. After this defeat, King James went back to France. The Jacobites faced another big loss at the Battle of Aughrim in 1691. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Limerick in October 1691.

One person who lived during the war, George Story, estimated that over 100,000 people died from sickness, hunger, or in battle. The war had a huge impact on Ireland. It made sure that British and Protestant rule would continue for more than 200 years. The Treaty of Limerick offered some protections for Catholics, but later laws, called the Penal Laws, took away many of their rights.

Contents

Why the War Started: The Background

The war began in March 1689 when James II and VII came to Ireland. He wanted to get his throne back after the Glorious Revolution in November 1688. That event had replaced him with his nephew William III and daughter Mary II. This conflict was part of the larger Nine Years' War (1688-1697) in Europe. This bigger war was between Louis XIV of France and the Grand Alliance, led by William. Both Louis and William saw Ireland as a smaller part of their bigger war. James's main goal was to get England back.

Ireland was chosen because about 75% of its people were Catholic, like James. Protestants mostly lived in Ulster, where they made up almost half the population. Ireland also had a large Catholic army, built up by the Earl of Tyrconnell since 1687. Most of these soldiers were new and poorly equipped. James brought weapons and French soldiers to help train them. However, the demands made by Irish Catholics for their support made many Protestants in England and Scotland less likely to support James. This was also true in Ulster. Without Ulster, James could not easily support the uprising in Scotland, invade England, or stop William from bringing in troops and supplies.

Irish Catholics wanted their land back. By 1685, Catholic land ownership had dropped from 90% in 1600 to only 22%. This was a big issue. However, Protestants and some wealthy Irish Catholics who had gained land from earlier deals, like Tyrconnell, did not want these changes. Another demand was for the Parliament of Ireland to have more power. This went against the ideas of the Stuart kings, who wanted a strong, united kingdom. These different goals among James's supporters weakened his campaign.

The War Unfolds

Early Battles in the North (1688–1689)

Before November 1688, James was so sure Ireland would stay loyal that he sent 2,500 Irish soldiers to England. This left Tyrconnell with fewer trained soldiers. Many of these Irish soldiers were arrested after William arrived in England. They were later sent to fight in a different war in Europe.

Tyrconnell seemed surprised by how quickly James lost power. He started talking with William, but this might have been a way to buy time. In January, William sent Richard Hamilton, an Irish Catholic soldier, to talk with Tyrconnell. But once Hamilton was back in Ireland, many believed he convinced Tyrconnell to stop negotiating.

In January, Tyrconnell ordered 40,000 new soldiers to be recruited. Almost all of them were Catholic. By spring 1689, the army had about 36,000 men, but they lacked experienced officers. It was impossible to pay, equip, and train so many. Many became Rapparees, or unofficial fighters, who were hard for Tyrconnell to control. It was easiest for them to get supplies by taking them from Protestants. Many Protestants fled to the North or to England, spreading fears of disaster.

Fears grew as areas outside towns became unsafe. This got worse when Dublin Castle ordered Protestant groups to give up their weapons. Many people left the countryside. The population of Derry grew from 2,500 in December to over 30,000 by April. Even some Catholics sought safety in big towns or abroad.

James landed in Kinsale on March 12. He brought French soldiers and volunteers from England, Scotland, and Ireland. This news caused William's supporters to protest in Belfast. Protestants were mainly in Ulster and cities like Sligo and Dublin. Tyrconnell tried to secure these areas with Catholic soldiers. On December 7, Catholic troops were not allowed into Derry. However, the Protestant town council still declared their loyalty to James.

William saw the conflict in Ireland as a French invasion. He wanted to attack France directly. But he agreed to send help to Ireland because abandoning the Irish Protestants was not popular in England and Scotland. On March 8, the English Parliament approved money for an army of 22,230 men for Ireland. These were new soldiers and European fighters. In return, Parliament agreed to join the Grand Alliance and the wider Nine Years' War.

Hamilton was made the Jacobite commander in the North. On March 14, he secured eastern Ulster by defeating a Williamite group at Dromore. On April 11, Viscount Dundee started a Jacobite uprising in Scotland. On April 18, James joined the siege of Derry. On April 29, the French landed more Jacobite soldiers at Bantry Bay. When William's reinforcements reached Derry in mid-April, the governor, Robert Lundy, told them to go back, saying the city could not be defended. Their commanders were later fired by William for being cowardly, and Lundy fled the town in disguise.

The Jacobites focused on western Ulster, especially Derry and Enniskillen. This was seen as a mistake. Eastern Ulster was more important because it allowed Irish and Scottish Jacobites to help each other. If it had been captured, it would have been much harder for William's forces to get supplies from England. By mid-May, William's position improved. On May 16, government forces kept control of Kintyre, cutting direct links between Scotland and Ireland. The main Jacobite army was stuck outside Derry. Their French soldiers were even less popular with their Irish allies than with their enemies. On June 11, four groups of Williamite reinforcements arrived on the Foyle, north of Derry.

The war in the North changed in the last week of July. Dundee's victory at Killiecrankie on July 27 was overshadowed by his own death and heavy losses for his troops. This ended the Scottish uprising as a serious threat. On July 28, William's forces broke the Jacobite blockade of Derry with naval support, ending the siege. The Jacobites burned the surrounding countryside and retreated south. On July 31, a Jacobite attack on Enniskillen was defeated at Newtownbutler. Over 1,500 men were killed, and their leader was captured. In just one week, the Jacobites lost their strong hold on Ulster.

On August 13, Schomberg landed in Belfast Lough with William's main army. By the end of August, he had more than 20,000 men. Carrickfergus fell on August 27. James wanted to hold Dundalk, but his French advisors wanted to retreat beyond the Shannon. Tyrconnell was not hopeful about their chances. Schomberg missed a chance to end the war by taking Dundalk, mainly because of problems with supplies.

Ireland was a poor country with a small population. Both armies needed help from outside. This was a bigger problem for the Jacobites. Schomberg's men lacked tents, coal, food, and clothes. This was because his new supply agent in Chester could not get enough ships. The situation got worse because they chose a camp on low, wet ground. Autumn rains and poor hygiene quickly turned it into a terrible swamp. Nearly 6,000 men died from disease before Schomberg ordered them to move to winter camps in November.

Jacobite Goals (1689–1690)

The Jacobites had different goals, which weakened their efforts. This was clear in the Irish Parliament that met from May to July. The Commons had 70 fewer members than it should have, and most members were Catholic. Most of these were from the 'Old English' families, who were of Anglo-Norman descent. A smaller number were from the old Gaelic families, called 'Old Irish'. In the Lords, five Protestant nobles and four Church of Ireland bishops were present.

This Parliament was called the "Patriot Parliament" by some historians. But it was actually very divided. For James, his main goal was to get England back. Giving too many things to his Irish supporters could weaken his position in England. In the early part of the war, Protestant support for James was more important than often thought. It included many members of the Church of Ireland. James was Catholic, but he still insisted on the rights of the established church.

Tyrconnell was loyal to James, but he saw protecting Catholic rights as more important than James getting his throne back. He and other Catholics who had gained land in 1662 did not want big changes to land ownership. This group wanted to make a deal with William in January. They were opposed by the 'Old Irish', who mainly wanted to get back the lands taken from them after the Cromwellian conquest in 1652.

Because of these differences, many in the Irish Parliament preferred to negotiate. This meant avoiding big battles to save the army and keep as much land as possible. James himself thought fighting in Ireland was a dead end. He said the French only sent enough supplies to keep the war going, not to win it. As a former naval commander, he believed taking England back meant invading across the English Channel. French ideas of invading via the Irish Sea were not realistic. The French navy could not even resupply their own forces in Ireland. So, they probably could not control the Irish Sea long enough to land troops in a hostile country.

France saw rebellions in Ireland and Scotland as a cheap way to make Britain use its resources away from Europe. This meant that making the war last longer was more useful than winning it quickly. This was very hard for the local people. In 1689, the French envoy d'Avaux told the Jacobites to retreat beyond the Shannon River. He wanted them to destroy everything in between, including Dublin. Not surprisingly, this idea was rejected. The Irish generally disliked the French, especially d'Avaux. The feeling was mutual. When d'Avaux was replaced in April 1690, he told his replacement that the Irish were "cowardly people, whose soldiers never fight and whose officers will never obey orders."

Key Battles: Boyne and Limerick (1690)

In April 1690, 6,000 more French soldiers arrived in Ireland. In return, 5,387 of the best Irish soldiers were sent to France. To keep as much land as possible, the Jacobites held a line along the River Boyne. They first destroyed or removed crops and animals to the north. This caused great suffering for the local people. It took over fifty years for the area around Drogheda to recover.

William's English government wanted him to deal with Ireland before fighting in Europe. So, William sent most of his available forces to Ireland and led the campaign himself. On June 14, 1690, 300 ships arrived in Belfast Lough. They carried nearly 31,000 men, including Dutch, English, and Danish soldiers. Parliament supported him with more money. The supply problems Schomberg faced were fixed. Transportation costs alone rose from £15,000 in 1689 to over £100,000 in 1690.

The Jacobites set up defenses on the south bank of the Boyne River at Oldbridge, near Drogheda. On July 1, William's forces crossed the river in several places. This forced the Jacobites to retreat. The battle was not a complete victory. Fewer than 2,000 people died on both sides. Schomberg was one of them. The Jacobite army, weakened by soldiers leaving, retreated to Limerick. William entered Dublin without a fight.

Elsewhere, the French won the Battle of Fleurus on July 1, gaining control of Flanders. On the same day as the Boyne, they defeated an Anglo-Dutch fleet at Beachy Head. This caused panic in England. As a former naval commander, James knew that controlling the Channel was a rare chance. He went back to France to push for an immediate invasion of England. However, the French did not follow up their victory. By August, the Anglo-Dutch fleet had regained control of the sea.

Tyrconnell had spent the winter of 1689-1690 asking Louis XIV to support an invasion of England, to avoid fighting in Ireland. His requests were denied. An invasion needed huge amounts of money, and Louis did not trust James or his English supporters. While James had good reasons for leaving quickly, he is remembered in Irish history as "James the coward."

William missed a chance to end the war because he thought his position was stronger than it was. The Declaration of Finglas on July 17 did not offer a pardon to Jacobite officers and Catholic landowners. This encouraged them to keep fighting. Soon after, James Douglas and 7,500 men tried to break the Jacobite defense line along the Shannon by taking Athlone. But they lacked siege cannons and had to retreat.

Limerick, a key city in western Ireland, became William's next target. The Jacobites gathered most of their forces there. A group of William's soldiers under Marlborough captured Cork and Kinsale. But Limerick fought off many attacks, causing heavy losses for William's army. Cavalry raids led by Patrick Sarsfield destroyed William's artillery. Heavy rain also prevented new cannons from arriving. Facing many threats in Europe, William pulled back and left Ireland in late 1690. The Jacobites still held large parts of western Ireland.

Dutch general de Ginkell took command, based in Kilkenny. Douglas was in Ulster, and the Danish soldiers were in Waterford. Protestant rule was brought back in the areas William controlled. Jacobite lands were taken and given to William's supporters. Ginkel said that paying William's supporters with money, not land, would be cheaper than a month of war. He pushed for more generous peace terms.

On July 24, a letter from James confirmed that ships were coming to take the French soldiers and anyone else who wanted to leave. He also released his Irish officers from their promises, allowing them to seek a negotiated end to the war. Tyrconnell and the French troops sailed from Galway in early September. James's inexperienced son was left in command, helped by a group of officers including Sarsfield.

Tyrconnell hoped to get enough French support to continue the war and get better terms. He told Louis that this could be done with a small number of French troops. A peace deal also required him to reduce the power of the "war party," led by Sarsfield, who was becoming very popular with the army. Tyrconnell told James that the war party wanted Ireland to be independent. He, however, wanted Ireland to be strongly linked to England. To do this, he needed weapons, money, and an "experienced" French general to replace Sarsfield and James's son.

Final Battles and Treaty (1691)

By late 1690, the Jacobites were split into a "Peace Party" and a "War Party." Those who supported Tyrconnell's efforts to negotiate with William included senior officers and political figures. Sarsfield's "War Party" believed William could still be defeated. Its leaders included English and 'Old English' officers.

William had finally given Ginkell permission to offer the Jacobites fair surrender terms. These included religious tolerance for Catholics. But when the "Peace Party" tried to accept in December, Sarsfield demanded that some leaders be arrested. This happened, likely with Tyrconnell's quiet approval. Tyrconnell returned from France to try to regain control by offering Sarsfield some deals.

King James was very worried about the split among his Irish supporters. He asked Louis XIV for more military help. Louis sent general Charles Chalmot, Marquis de Saint-Ruhe, to replace James's son as commander of the Irish Army. Saint-Ruhe had secret orders to check the situation and help Louis decide whether to send more military aid. Saint-Ruhe arrived at Limerick on May 9. He brought enough weapons, corn, and food to support the army until autumn, but no troops or money.

By late spring, Ginkell was worried that French ships might bring more soldiers to Galway or Limerick. He started preparing his army to move quickly. In May, both sides gathered their forces for a summer campaign. The Jacobites were at Limerick, and William's forces were at Mullingar. Small fights continued.

On June 16, Ginkell's cavalry began scouting from Ballymore towards Athlone. Saint-Ruhe had spread out his forces along the Shannon River. But by June 19, he realized Athlone was the target and started bringing his troops together west of the town. Ginkell broke through the Jacobite defenses and took Athlone on June 30 after a short but bloody siege. Saint-Ruhe failed to help the soldiers there and fell back to the west.

Taking Athlone was a big victory for William's forces. It was thought that Saint-Ruhe's army would likely fall apart if the Shannon was crossed. The leaders in Dublin offered generous terms for Jacobites who surrendered. These included a full pardon, getting back their lost lands, and the chance to join William's army with the same or higher rank. The Jacobite command fell apart with arguments. Sarsfield's group accused others of betrayal. Saint-Ruhe's second-in-command sided with Tyrconnell, who made him governor of Galway.

Ginkell did not know where Saint-Ruhe's main army was. He thought he was outnumbered. On July 10, Ginkell continued to move carefully through Ballinasloe towards Limerick and Galway. Saint-Ruhe's first plan, supported by Tyrconnell, was to fall back to Limerick. This would force William's army to fight for another year. But Saint-Ruhe wanted to make up for his mistakes at Athlone. He decided to force a big battle instead. Ginkell, with 20,000 men, found his way blocked by Saint-Ruhe's army, which was about the same size, at Aughrim on the morning of July 12. The Battle of Aughrim was a disaster for the Jacobites. Saint-Ruhe was killed, many senior Jacobite officers were captured or killed, and the Jacobite army was shattered.

D'Usson took over as commander. He surrendered Galway on July 21, getting good terms. After Aughrim, the remaining Jacobite soldiers retreated to the mountains. They then regrouped under Sarsfield's command at Limerick. The defenses there were still being fixed. Many Jacobite infantry groups were very small, though some stragglers arrived later. Tyrconnell, who had been sick, died at Limerick soon after. This meant the Jacobites lost their main negotiator. Sarsfield and the main Jacobite army surrendered at Limerick in October after a short siege.

The Treaty of Limerick

Sarsfield, now the most senior Jacobite commander, signed the Treaty of Limerick with Ginkel on October 3, 1691. This treaty promised freedom of worship for Catholics. It also offered legal protection for any Jacobites who swore loyalty to William and Mary. However, the lands of those killed before the treaty could still be taken. The treaty also agreed to Sarsfield's demand that soldiers still in the Jacobite army could leave for France. This event became known as the "Flight of the Wild Geese". It started almost immediately and was finished by December.

Today, experts believe about 19,000 soldiers and irregular fighters left. Including women and children, the number was slightly over 20,000. This was about one percent of Ireland's population. Some soldiers reportedly had to be forced onto the ships when they learned they would join the French army. Most could not bring or contact their families. Many seem to have left the army on the way from Limerick to Cork, where the ships departed.

What Happened Next

The "Wild Geese" first formed King James II's army in exile. After James died, they joined France's Irish Brigade. This brigade had been set up in 1689 with the 6,000 troops who went with Mountcashel. Disbanded Jacobites still posed a risk in Ireland. William encouraged them to join his own army, even though English and Irish parliaments resisted. By the end of 1693, another 3,650 former Jacobites had joined William's forces fighting in Europe. The Lord Lieutenant eventually limited enlistment to "known Protestants." The last remaining Jacobite soldiers in Ireland were sent home with money to keep the peace.

Meanwhile, the English Parliament passed a law in 1691. This law required anyone taking an oath, like lawyers or doctors, to deny a Catholic belief called transubstantiation. This effectively stopped all Catholics from holding such positions. Despite this, many Protestants were angry. They felt the treaty had let the Jacobites off too easily. The fact that the government stopped searches for Jacobite weapons was seen as favoring Catholics. Some even rumored that a high-ranking official was a "secret Jacobite."

Fears continued about Catholics possibly supporting a French invasion. In 1695, a new Lord Deputy was appointed, and attitudes changed. That same year, the Irish Parliament passed the Disarming Act. This law stopped Catholics, except for those protected by the Limerick treaty, from owning weapons or horses worth more than £5. A second 1695 law aimed to stop Irish Catholics from having foreign connections. It specifically targeted the country's "English ancient families." This law stopped Catholics from sending their children to study abroad. Catholic nobles saw these actions as a serious betrayal. This feeling was captured in the phrase "remember Limerick and Saxon perfidy," supposedly used by Irish soldiers in France later on. However, despite later harsh laws, those protected by the Limerick treaty generally remained exempt for the rest of their lives.

Long-Term Effects of the War

The Williamite victory in Ireland had two main long-term results. First, it made sure that James II would not get his thrones back in England, Ireland, and Scotland through war. Second, it made sure that British and Protestant rule over Ireland became stronger. For over a century, Ireland was ruled by what was called the "Protestant Ascendancy." This was mostly a Protestant ruling class. The majority Irish Catholic community and the Ulster-Scots Presbyterian community were kept out of power, which was based on owning land.

For more than 100 years after the war, Irish Catholics felt a strong connection to the Jacobite cause. They saw James and the Stuart kings as the rightful rulers who would have given Ireland a fair deal. This included self-government, getting back confiscated lands, and tolerance for Catholicism. Thousands of Irish soldiers left Ireland to serve the Stuart kings in the Spanish and French armies. Until 1766, France and the Pope still wanted to put the Stuarts back on the British thrones. At least one Irish battalion from the French service fought on the Jacobite side in the Scottish Jacobite uprisings until the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

The war also led to Irish Protestant nobles joining the British army's officer ranks. By the 1770s, Irish Protestants made up about one-third of all officers. This was a very large number compared to their population.

Protestants saw the Williamite victory as a win for religious and civil freedom. Today, murals of King William still appear on walls in Ulster. The defeat of the Catholics in the Williamite war is still celebrated by Protestant Unionists through the Orange Order on the Twelfth of July.

See also

- Jacobite rising of 1689

- Monmouth Rebellion

- Early Modern Ireland 1536-1691

- Ireland 1691-1801

- Danish Auxiliary Corps in the Williamite War in Ireland

Images for kids

-

Schomberg (1615–1690), Williamite commander in Ireland; immensely experienced, he was a Marshal of France, England and Portugal.