Battle of Aughrim facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Aughrim |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Williamite War in Ireland and the Nine Years' War | |||||||

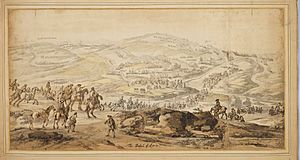

Contemporary sketch of Aughrim, viewed from the Williamite lines, by Jan Wyk |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 | 20,000-25,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000 killed | 4,000 killed 4,000 missing 581 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Aughrim (Irish: Cath Eachroma) was a very important battle in the Williamite War in Ireland. It happened on July 12, 1691, near the village of Aughrim, County Galway. This battle was fought between the Jacobite army, who supported King James II, and the forces of King William III.

This battle was one of the bloodiest ever fought in the British Isles. Around 7,000 people lost their lives. The Jacobites' defeat at Aughrim basically ended King James's fight in Ireland. Even though the city of Limerick kept fighting for a while, Aughrim was the turning point.

Contents

Why Did the Battle Happen?

By 1691, the Jacobite army was mostly trying to defend itself. The year before, they had moved back into Connacht. This area was easy to defend because it was behind the Shannon River. They had strong forts at Sligo, Athlone, and Limerick to protect the routes into the area and the western ports.

King William had tried to attack Limerick in August 1690. But he lost many soldiers and decided to stop the attack. He sent his army to rest for the winter. Meanwhile, the Jacobite leaders were having disagreements. King James had left for France after losing the Battle of the Boyne, which made things worse.

Two Sides of the Jacobite Army

There were two main groups among the Jacobites. One was the "Peace Party," led by Tyrconnell. They wanted to make a deal with King William. The other was the "War Party," led by Patrick Sarsfield. They believed they could still win the war.

Sarsfield's group was encouraged when William failed to take Limerick. They asked King Louis XIV of France for help. They wanted Tyrconnell and the army commander, Berwick, to be removed. They also asked Louis to send military aid.

The "Peace Party" got an offer from William's side in December. Sarsfield then demanded that Berwick arrest some "Peace Party" leaders. Berwick did this, probably with Tyrconnell's agreement. Tyrconnell had returned from France and was trying to stay important by joining Sarsfield's group.

King James was worried about the Jacobite leaders fighting among themselves. He asked King Louis for more military support. Louis sent General Charles Chalmot de Saint-Ruhe to lead the Jacobite army. Saint-Ruhe arrived in Limerick on May 9. He brought enough weapons and food for the army. However, he did not bring the extra soldiers or money that the Jacobites really needed.

Williamite Army's Plan

By this time, King William's forces were led by a Dutch officer named Godert de Ginkel. His second-in-command was Württemberg. Ginkel knew that William's army in the Netherlands was in a tough spot. He wanted to end the war quickly in Ireland. William allowed him to offer the Jacobites fair terms if they surrendered.

In spring 1691, Ginkel worried that French ships might bring more soldiers to Galway or Limerick. So, he started planning to attack as soon as possible. Both sides began gathering their armies for the summer. The Jacobites were in Limerick, and the Williamites were in Mullingar.

On June 16, Ginkel's cavalry (soldiers on horseback) checked out the Jacobite fort at Athlone. Saint-Ruhe wasn't sure where Ginkel would try to cross the Shannon River. But by June 19, he realized Athlone was the target. He started moving his troops west of the town.

Ginkel broke through the Jacobite defenses and took Athlone on June 30 after a bloody fight. Saint-Ruhe could not help the town and moved his army back to the west. Taking Athlone was a big victory. It seemed like it might make the Jacobite army fall apart. The leaders in Dublin offered good terms to Jacobites who surrendered. They could get a free pardon, get their land back, and even join William's army with the same or higher rank.

Ginkel didn't know where Saint-Ruhe's main army was. He thought he was outnumbered. So, on July 10, Ginkel slowly moved through Ballinasloe towards Limerick and Galway. Saint-Ruhe and Tyrconnell had planned to fall back to Limerick. This would force the Williamites to fight for another year. But Saint-Ruhe wanted to make up for his mistakes at Athlone. He decided to force a big battle instead. On the morning of July 12, 1691, Ginkel found his way blocked by Saint-Ruhe's army at Aughrim.

Who Fought at Aughrim?

At the time of the battle, both armies had about 20,000 soldiers. The Jacobite army was mostly made up of Irish soldiers. Tyrconnell had reorganized this army since 1686. He had removed most Protestant officers and soldiers. Many new Irish Catholic regiments had joined, trained in the English military style.

We don't know for sure which Jacobite infantry (foot soldiers) regiments fought at Aughrim. But at least 30 are thought to have been there. These included the Foot Guards, Talbot's, Nugent's, and others. The Jacobites also had about 4,000 cavalry and dragoons (soldiers who could fight on horseback or on foot). These were usually better trained than their foot soldiers.

Ginkel's army is better known. Besides English regiments, it had many Anglo-Irish Protestants. It also included Dutch, Danish, and French Huguenot (French Protestant) soldiers. Different reports describe Ginkel's army in different ways. But most agree that the right side had English, Anglo-Irish, and Huguenot cavalry. The left side had Danish and French cavalry. Ginkel put the English infantry on the right of his center. The French, Danish, and Dutch foot soldiers were on their left.

How Were the Armies Positioned?

People who saw the battle said the Jacobite lines at Aughrim were in a very strong defensive spot. It stretched for over two miles. To protect his mostly new infantry, Saint-Ruhe placed most of them on a ridge called Kilcommadan Hill. Their positions were protected by small fences and hedges.

The middle of their line was also protected by a large bog (wet, muddy ground). This bog was too difficult for cavalry to cross. The Melehan River flowed through it. The left side was also bordered by a "large Red Bogg" that was almost a mile wide. There was only one narrow path through it. This path was watched over by the empty village of Aughrim and a ruined castle. Saint-Ruhe put most of his cavalry here.

On the right side, the Tristaun stream ran through a pass. This was a more open and weaker spot. Saint-Ruhe put his best infantry and some cavalry regiments here. These were all under his second-in-command, the chevalier de Tessé. One person who was there said that Patrick Sarsfield had argued with Saint-Ruhe. Sarsfield was placed with the cavalry reserve at the back left. He was told not to move without direct orders.

The Battle Begins

After a thick mist all morning, Ginkel's forces got into position around two in the afternoon. Both sides fired cannons at each other for the next few hours. Ginkel wanted to avoid a full battle until the next day. He ordered a small attack on the Jacobites' weaker right side. This attack was led by a captain and sixteen Danish troopers, followed by 200 dragoons.

The Jacobite response showed how strong their defenses were. It also meant that Ginkel's attackers could no longer stop the fight as he had planned. Around 4 pm, a meeting was held. Ginkel still wanted to pull back. But the Williamite infantry general Hugh Mackay argued for a full attack right away.

The real battle started between five and six o'clock. In the middle, the English and Scots regiments tried to attack the Jacobite infantry on Kilcommadan Hill head-on. The attackers had to cross water that was waist-deep. They also faced strong Irish defenses from the reinforced hedges. They had to retreat with many losses. The Jacobites chased them downhill, capturing some colonels.

On their left side, the Williamites moved across low ground. They were open to Jacobite fire and lost many soldiers. The Williamite attack in this area was pushed back into the bog by the Irish foot soldiers. Many attackers were killed or drowned. In the chaos, the chasing Jacobites managed to damage some Williamite cannons. The Jacobite regiments of the Guards and Gordon O'Neill were said to have fought especially well. The gunfire was so heavy that "the ridges seemed to be ablaze," according to a Norwegian soldier fighting with the Danish army.

Turning Point

The Jacobite right and center were holding strong. So, Ginkel tried to force his way across the narrow path on the Jacobite left. Any attack here would have to go along a narrow lane. This lane was covered by Walter Burke's regiment from their positions in Aughrim castle. Four battalions (groups of soldiers) got positions near the castle. After this, Compton's Royal Horse Guards crossed the path on their third try.

Earlier, the Jacobite commander Dorrington had moved two battalions of infantry from this area to help the Jacobite center. So, the Williamites faced only weak resistance. They reached Aughrim village. A group of Jacobite cavalry and dragoons was supposed to cover this side. But their commander, Luttrell, had ordered them to fall back. This path is now known as "Luttrell's Pass." There were rumors that he was paid by William. But it's more likely that Luttrell pulled back because he had little or no infantry support. Other cavalry regiments also crossed the path, attacking the Jacobite flank.

Most people, even those who supported William, agreed that the Irish foot soldiers fought extremely well. Some accounts say Saint-Ruhe was "in a transport of joy" to see his foot soldiers fight so bravely.

Saint-Ruhe seemed to believe the battle could be won. He was heard shouting, "they are running, we will chase them back to the gates of Dublin!" He then rode across the battlefield to lead the defense against the Williamite cavalry on his left side. However, as he rode to rally his cavalry, Saint-Ruhe stopped briefly to direct some cannon fire. He was then hit by a cannonball and killed. His death happened around sunset, shortly after eight o'clock.

After Saint-Ruhe died, the Jacobite left side quickly fell apart. They had no senior commander. The Horse Guards left the field almost immediately. The cavalry and dragoon regiments followed soon after. De Tessé tried to lead a cavalry counter-attack but was badly wounded. The Jacobite left side was now open. Mackay and Tollemache also attacked again in the center. They pushed the Jacobites towards the hilltop. Burke and his regiment, still holding the castle, had to surrender.

Most of the infantry did not know Saint-Ruhe had died. Hamilton's infantry on the Jacobite right continued to fight back. They fought the Huguenot foot soldiers to a standstill in an area still known as the "Bloody Hollow." Around nine o'clock, as night fell, the Jacobite infantry were finally pushed to the top of Killcommadan hill. They broke and ran towards a bog behind their position. Their cavalry retreated towards Loughrea.

Sarsfield and Galmoy tried to organize a small group to fight off the Williamites. But like in many battles of that time, most of the Jacobite soldiers were killed while they were running away. The Williamite cavalry chased them until darkness, mist, and rain stopped them. Hundreds of defeated infantry soldiers were cut down as they tried to escape. Many had thrown away their weapons to run faster.

Many experienced Jacobite officers were killed or captured. These included several brigadiers and colonels. The two main generals leading the Jacobite center were both captured. One of them died from his wounds soon after. Some Jacobite soldiers were accused of killing a Williamite colonel after he was captured. One Jacobite source claimed that about 2,000 Jacobites were killed "in cold blood" after being promised safety.

A Williamite soldier named George Story wrote that from the top of the hill where the Jacobite camp had been, the bodies "looked like a great Flock of Sheep, scattered up and down the Countrey for almost four Miles round."

What Happened After Aughrim?

It's hard to know exactly how many soldiers were lost on each side. But the losses were very high. It is generally agreed that 7,000 men were killed at Aughrim. Some people call Aughrim "quite possibly the bloodiest battle ever fought in the British Isles."

At the time, the Williamites said they lost only 600 men and killed about 7,000 Jacobites. Some newer studies say Williamite losses were as high as 3,000. But they are more often given as 3,000, with 4,000 Jacobites killed. Another 4,000 Jacobites had run away. Ginkel recorded 526 prisoners. Even though Ginkel had promised that the captured soldiers would be treated fairly, the high-ranking officers were sent to the Tower of London as state prisoners. Most of the regular soldiers were sent to Lambay Island, where many died from sickness and hunger.

Aughrim was the most important battle of the war. The Jacobites had lost many experienced officers. They also lost much of their army's equipment and supplies. The remaining Jacobite soldiers went to the mountains. Then they regrouped under Sarsfield's command at Limerick. Many of their infantry regiments were very small after the battle. For example, one regiment had only 240 soldiers left.

The city of Galway surrendered without a fight after the battle. They got good terms for their surrender. Sarsfield and the main Jacobite army surrendered soon after at Limerick, after a short siege.

How Aughrim is Remembered

The battle "made a searing impression on the Irish consciousness" (meaning it deeply affected Irish memory). In Irish tradition, the battle became known as "Eachdhroim an áir" – "Aughrim of the slaughter." This name comes from a poem by an Irish-language poet.

Ginkel ordered his own dead to be buried. But the Jacobite soldiers were left unburied. Their bones were scattered on the battlefield for years. The poet wrote that their "damp bones" were "lying uncoffined."

A writer named John Dunton visited Ireland seven years after the battle. He wrote that the English did not bury the enemy dead. He said there were not enough people to bury them. Many dogs came to the battlefield and ate human flesh. They became so dangerous that a single person could not pass safely. He also told a story about a loyal greyhound dog. It belonged to a Jacobite soldier killed in the battle. The dog stayed by its master's body, protecting it, until a soldier shot it the next year.

Aughrim was a sad symbol for Irish Catholics. But it was also a day of celebration for Loyalists (especially the Orange Order) in Ireland. They celebrated it on July 12 until the early 1800s. After that, the Battle of the Boyne became more important for their celebrations on "the Twelfth." This happened because of the change to the Gregorian calendar.

Some people think the Boyne became more important because the Irish troops could be shown as cowardly there. At Aughrim, they were generally agreed to have fought bravely. The Loyalist song The Sash still mentions Aughrim.

The battle was also the subject of a play in 1728 called The Battle of Aughrim or the Fall of Monsieur St Ruth. At first, no one paid much attention to it. But from 1770 onwards, it became very popular. The play was meant to celebrate the Williamite victory. It showed Saint-Ruhe as the bad guy. But it also showed Sarsfield and his officers as heroes. It included a "lament for Catholic patriotism." So, both Catholics and Protestants liked the play for many years. In 1804, it was said that "a more popular Production never appeared in Ireland." Many peasants who could read English had it, and they memorized it.

In 1885, artist John Mulvany finished a painting of the battle. It was shown in Dublin in 2010. The Battle of Aughrim was also the subject of a long poem in 1968 by Richard Murphy. He noted that he had ancestors who fought on both sides of the battle.

The Aughrim battlefield site caused some arguments in Ireland. There were plans to build the new M6 motorway through the battlefield. Historians, environmentalists, and members of the Orange Order did not like these plans. The motorway opened in 2009.

Aughrim Interpretative Centre

The Battle of Aughrim Interpretative Centre is in Aughrim village. It opened in 1991. It is a project by the Aughrim Heritage Committee, Ireland West Tourism, and Galway County Council. The center has items found on the battlefield. It also has 3D displays and a documentary film. The film explains how the battle happened and why it was important in Irish history.

See also

- List of conflicts in Ireland

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |