Siege of Limerick (1690) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Limerick (1690) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Williamite War in Ireland | |||||||

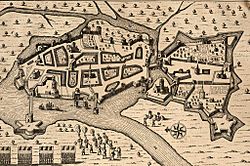

A 1690 etching of the siege |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 men | 14,500 infantry in Limerick 2,500 cavalry in Clare |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~3,000 killed in assault 2,000 died of disease |

~400 killed in action | ||||||

Limerick, a city in western Ireland, was attacked twice during the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–1691). The first attack happened in August and September 1690. During this time, the city's defenders, known as Jacobites, had moved back to Limerick after losing the Battle of the Boyne. The attacking army, called the Williamites, led by King William III, tried to capture Limerick by force. However, they were pushed back and had to leave for the winter.

Contents

Why Limerick Was Important

After successfully defending Derry and Carrickfergus, the Jacobites lost control of northern Ireland by late 1689. Their defeat at the Battle of the Boyne on July 1, 1690, forced them to retreat quickly from eastern Ireland. They also had to give up their capital city, Dublin. King James II himself left Ireland for France, believing he could not win the war.

The Irish Jacobites who remained found themselves in a difficult spot. They were trapped in an area behind the River Shannon, with their main strongholds being Limerick and Galway. The main Jacobite army had retreated to Limerick after their loss at the Boyne.

Disagreement Among Leaders

Some Jacobite leaders, like Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, wanted to give up. They hoped to get good surrender terms from the Williamites. However, Irish officers, such as Patrick Sarsfield, wanted to keep fighting. Many Jacobite officers did not want to surrender because King William had offered very harsh terms after his victory at the Boyne. These terms only offered a pardon to the regular soldiers, not to the officers or landowners.

The French commander helping the Jacobites, Lauzun, also wanted to surrender. He thought Limerick's defenses were very weak. He even said they could be "knocked down by roasted apples," meaning they were useless.

Limerick's Defenders

Despite these worries, there were enough Jacobite soldiers to defend Limerick. About 14,500 Jacobite foot soldiers were inside Limerick. Another 2,500 horse soldiers (cavalry) were in County Clare under Sarsfield's command.

The ordinary soldiers were still in good spirits, even after the defeat at the Boyne. This was partly because of an old Irish story. It said that the Irish would win a great victory against the English outside Limerick and drive them out of Ireland. This might seem strange today, but such stories were very important in Irish culture back then. The Williamites made fun of these beliefs in songs like Lillibullero.

Lauzun's second-in-command, Marquis de Boisseleau, supported those who wanted to defend the city. He worked hard to improve Limerick's defenses.

Sarsfield's Surprise Attack

King William of Orange and his army, with 25,000 men, arrived at Limerick on August 7, 1690. They took over Ireton's Fort and Cromwell's Fort, which were outside the city. However, William only had his smaller field cannons with him. His large siege cannons, needed to break down city walls, were still on their way from Dublin with a small guard.

Sarsfield's cavalry, about 600 men guided by "Galloping Hogan", attacked this supply train at Ballyneety. They destroyed William's siege cannons and ammunition. This meant William had to wait another ten days before he could start seriously attacking Limerick. He had to bring another set of siege cannons all the way from Waterford.

The Main Attack on Limerick

By the time the new cannons arrived, it was late August. Winter was coming, and King William wanted to finish the war in Ireland. He needed to return to the Netherlands to focus on the bigger war against France, known as the War of the Grand Alliance. Because of this, he decided to launch a full-scale attack on Limerick.

His siege cannons blasted a large hole, called a breach, in the walls of the "Irish town" part of the city. William launched his attack on August 27. Danish grenadiers (soldiers who threw small bombs) were the first to rush into the breach. But Boisseleau had built a strong earth wall inside the city and put up barricades in the streets. These made it very hard for the attackers to move forward.

The Danish grenadiers and the eight regiments that followed them into the breach suffered terrible losses. They were hit by musket and cannon fire from very close range. Jacobite soldiers who didn't have weapons, and even ordinary people (including, famously, women), stood on the walls. They threw stones and bottles at the attackers. A regiment of Jacobite dragoons (horse soldiers) also rode out and attacked the Williamites in the breach from the outside. After three and a half hours of intense fighting, William finally ordered his troops to stop the attack.

Williamites Retreat

William's army had about 3,000 casualties (killed or wounded). Many of these were his best Dutch, Danish, German, and Huguenot troops. The Jacobites, in contrast, had lost only about 400 men in the battle.

The weather got worse, so William decided to end the siege. He sent his troops to their winter camps, where another 2,000 of them died from disease. William himself left Ireland soon after and went back to London. He then took command of the Allied forces fighting in Flanders. He left Godert de Ginkell in charge of the army in Ireland. The next year, Ginkell won a very important victory at the Battle of Aughrim.

After the siege, William Dorrington became the governor of Limerick. Work began to make the city's defenses even stronger. Limerick remained a Jacobite stronghold until it finally surrendered after another Williamite attack the following year. After losing their last major stronghold, Patrick Sarsfield led the Jacobite army into exile. This event is known as the Flight of the Wild Geese. These soldiers continued to serve King James and his successors in other parts of Europe.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |