Flight of the Wild Geese facts for kids

The Flight of the Wild Geese was when an Irish army, led by Patrick Sarsfield, left Ireland for France. This happened on October 3, 1691, after a peace agreement called the Treaty of Limerick ended the Williamite War in Ireland.

More generally, the name Wild Geese refers to Irish soldiers who left Ireland to join armies in other European countries during the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s. Before the main "Flight" in 1691, some Irish soldiers had already gone to France in 1690. They formed the French Irish Brigade.

Contents

Irish Soldiers in European Armies

Serving Spain: The First Wild Geese

The first Irish soldiers to fight as a group for a European country joined the Spanish army in the 1590s. They were part of the Army of Flanders during the Eighty Years' War. These soldiers were recruited in Ireland by an English Catholic named William Stanley. He was supposed to lead them for England, but he switched sides to Spain in 1585. This unit fought in the Netherlands until it was disbanded around 1600.

After the Nine Years' War ended in Ireland, many Irish leaders, including Hugh O'Neill and Rory O'Donnell, fled Ireland in 1607. This event is known as the "Flight of the Earls". They hoped to get help from King Philip III of Spain to restart their fight in Ireland. However, the King did not want another war with England and said no.

Still, their arrival led to a new Irish regiment being formed in Flanders, which is now part of Belgium. This regiment was made up of Irish nobles and their followers. It was very against English Protestant rule in Ireland. Owen Roe O'Neill and Hugh Dubh O'Neill were important officers in this group.

More Irish Catholics joined these units in the early 1600s. This was because Catholics were not allowed to hold military or political jobs in Ireland. Many of these soldiers returned to Ireland in 1641 to fight in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. After the Irish Catholics were defeated and Ireland was taken over by Cromwell, about 34,000 Irish soldiers left to serve in Spain. Some later moved to French service because conditions were better there.

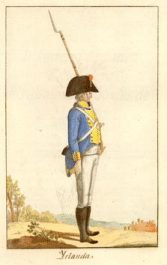

During the 1700s, Spain's Irish regiments fought not only in Europe but also in the Americas. For example, the Irlanda Regiment was in Havana, Cuba, from 1770 to 1771. The Ultonia Regiment was in Mexico from 1768 to 1771. The Regiment of Hibernia was in Honduras from 1782 to 1783.

By the time of the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s, these three Irish regiments were still part of the Spanish army. However, it became harder to find Irish recruits. By 1811, the Hibernia Regiment had to be filled with Spanish soldiers. All three regiments were finally disbanded in 1818 because they could not find enough Irish or other foreign recruits.

Serving France: A New Home for Irish Soldiers

From the mid-1600s, France became the main country for Irish Catholics seeking a military career. It was easier to travel to France from Ireland, and French and Irish interests often aligned.

France hired many foreign soldiers, including Germans, Italians, Irish, Scottish, and Swiss. About 12% of all French troops in peacetime were foreigners, and this number rose to 20% during wars. Irish regiments in French service were paid more than French soldiers. Both Irish and Swiss regiments wore red uniforms, but this was not related to the British "redcoats".

A major change happened during the Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691). King Louis XIV of France sent help to the Irish Jacobites. In 1690, France sent 6,000 French troops to Ireland. In return, Louis XIV asked for 6,000 Irish recruits for his war against the Dutch. These Irish soldiers formed the first French Irish Brigade.

A year later, after the Irish Jacobites, led by Patrick Sarsfield, agreed to peace terms at the Treaty of Limerick in 1691, the Irish army left for France. Sarsfield sailed on December 22, 1691, leading about 19,000 people, including 14,000 soldiers and 6,000 women and children. This event is known as the Flight of the Wild Geese. The poet W. B. Yeats later wrote about it:

Was it for this the Wild Geese spread

A grey wing on every tide…

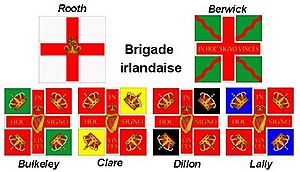

Sarsfield's Irish army was reorganized and given red uniforms, showing their loyalty to the Stuart king. In 1692, a large French and Irish army gathered to invade England. However, the invasion was stopped after the French navy lost a big battle. Sarsfield's Wild Geese then joined the existing Irish Brigade.

Until 1745, Irish Catholic nobles were allowed to quietly recruit soldiers for France. The British authorities in Ireland thought this was better than having many unemployed young men in the country. But in 1745, a group of Irish soldiers from the French army helped a rebellion in Scotland. After this, the British realized the danger and banned recruiting for foreign armies in Ireland. From then on, most of the regular soldiers in the Irish units in France were not Irish, though the officers continued to be from Irish families.

During the Seven Years' War, efforts were made to find recruits among Irish prisoners of war or soldiers who left the British Army. Otherwise, only a few Irish volunteers managed to travel to France, or the sons of former Irish Brigade members who lived in France joined. By the end of the 1700s, even the officers of the Irish Regiments were from Franco-Irish families who had lived in France for many generations. These families often kept their Irish heritage.

After the French Revolution began, the Irish Brigade stopped being a separate group on July 21, 1791. The remaining Irish regiments, like Dillon's and Berwick's, lost their red uniforms and special status. However, they were still informally called by their old names. Many Franco-Irish officers left the service in 1792 when King Louis XVI was removed from power, as their loyalty was to him.

In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte created a new Irish unit called the Irish Legion. It was made up mostly of veterans from the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Napoleon wanted this Legion to lead an invasion of Ireland. The unit wore emerald-green uniforms with gold. Their flag had a gold harp on a green background. It said "The First Consul to United Ireland" and "Freedom of Conscience/Independence to Ireland".

The Irish Legion fought bravely in different wars, including the Walcheren Expedition and the Peninsular War. They were known for their courage, especially during the Siege of Astorga in 1812. The last major action for the Irish unit in France was during the Siege of Antwerp in 1814. They defended the city for three months against British forces. The siege ended after Napoleon gave up his power, and the Irish unit was soon disbanded. This ended a 125-year-old tradition of Irish military service in France.

Serving Austria: Irish Commanders and Heroes

Many Irish officers and soldiers also served in the armies of other European powers, including the Austrian Habsburg Empire. It was common for Irish commanders in the Habsburg Empire to face enemy armies also led by Irishmen. These were often men they had fought alongside in Ireland.

One example was Peter Lacy, a high-ranking officer in the Russian army. His son, Franz Moritz Graf von Lacy, became a famous general in the Austrian army. General Maximilian Ulysses Graf von Browne, an Austrian commander, was also of Irish descent.

Irish recruits for Austria came from areas like the midlands of Ireland. Members of the Taaffe, O'Neill, and Wallis families served with Austria. Count Alexander O'Nelly (O'Neill) from Ulster commanded an infantry regiment from 1734 to 1743. Earlier, in 1634, during the Thirty Years' War, Irish officers helped assassinate General Albrecht von Wallenstein on the Emperor's orders.

Later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, more Irish officers served the Habsburg Empire. These included Andreas O'Reilly von Ballinlough, who fought in many wars, and Laval Nugent von Westmeath. Maximilian Graf O’Donnell von Tyrconnell even saved the life of Emperor Franz Joseph I during an assassination attempt. Finally, Gottfried von Banfield became the most successful Austro-Hungarian naval pilot in the First World War.

Serving Sweden and Poland

In 1609, Arthur Chichester, the English leader in Ireland, sent 1,300 former Irish rebel soldiers from Ulster to serve in the Protestant Swedish Army. However, many of them left to join the Catholic Polish army.

These Catholic Irish troops in Swedish service switched sides during the Battle of Klushino against Poland. The Irish then served Poland for several years during the Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618), until they stopped getting paid.

The End of the Wild Geese Era

Irish recruitment for armies in other European countries greatly decreased after it was made illegal in 1745. This meant that recruiting within Ireland itself mostly stopped. Irishmen who wanted to join foreign armies had to travel to Europe on their own. As a result, new soldiers were increasingly the descendants of Irish soldiers who had settled in France or Spain, or they were non-Irish recruits like Germans or Swiss.

By the late 1780s, there were still three Irish regiments in France. During the Napoleonic Wars, units that were at least named "Irish" continued to serve in the Spanish and French armies. During the Franco-Prussian War, a volunteer Irish medical unit, the Franco-Irish Ambulance Brigade, served with the French Army.

It took some time for the British army to start recruiting Irish Catholic men. In the late 1700s, laws against Catholics were slowly eased. In the 1790s, laws stopping Catholics from carrying weapons were removed. After this, the British began forming Irish regiments for their own army, such as the Connaught Rangers. Several more Irish-named units were created in the 1800s.

By 1914, British Army infantry regiments linked to Ireland included the Prince of Wales's Leinster Regiment, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, the Irish Guards, and others. When the Irish Free State was created in 1922, five of these regiments were disbanded. The remaining ones were combined over time. Today, the United Kingdom still has four Irish-named regiments: the Irish Guards, the Royal Irish Regiment, the Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry, and the London Irish Rifles. Other regiments, like the Queen's Royal Hussars, keep their Irish heritage through their uniforms and traditions, such as celebrating St. Patrick's Day.

See also

- Battle of Pensacola (1781)

- Count Joseph Cornelius O’Rourke

- Early Modern Ireland 1536–1691

- Great Britain in the Seven Years' War

- Ireland 1691–1801

- Saint Patrick's Battalion

- The Wild Goose

- 5 Commando (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- The Wild Geese

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |