History of Ireland (1691–1800) facts for kids

The history of Ireland from 1691 to 1800 was a time when a group called the Protestant Ascendancy held most of the power. These were families from the Church of Ireland (a Protestant church), whose English ancestors had moved to Ireland. They had taken control of most of the land. Some of these landowners lived in England, but many lived in Ireland and started to feel more and more Irish.

During this time, Ireland was officially a separate kingdom with its own Parliament. However, it was really controlled by the King of Great Britain and his government in London. Most people in Ireland were Roman Catholics. They were not allowed to own land or have political power because of strict rules called the Penal Laws. The second largest group, the Presbyterians in Ulster, owned land and businesses. But they also couldn't vote or have political power.

This period started after the Catholic supporters of King James II were defeated in the Williamite War in Ireland in 1691. It ended with the Acts of Union 1800. These laws officially joined Ireland with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom starting on January 1, 1801. They also closed down the Irish Parliament.

Contents

Life and Money in Ireland

After the wars of the 1600s, much of Ireland's forests were cut down. The land was then used to raise animals for export. Things like salted beef, pork, butter, and cheese were sent from Cork to England, the British navy, and the sugar islands in the West Indies.

Even though Ireland produced a lot of food, many people were very poor and hungry. In the 1740s, a very cold winter and bad harvests led to the famine of 1740–1741. About 400,000 people died during this terrible time. Later, in the 1780s, landowners started growing grain for export instead of raising animals. Their poor tenants mostly ate potatoes and groats.

Farmers and Secret Societies

Poor farmers often formed secret groups to try and change how landlords treated them. These illegal groups had names like the Whiteboys, the Rightboys, the Hearts of Oak, and the Hearts of Steel. They were upset about high rents, being forced off their land, and having to pay taxes (called tithes) to the Anglican Church of Ireland.

These groups would sometimes harm livestock, tear down fences, or even use violence against landlords or officials. More and more people were born in Ireland during this time, which made the problems in the countryside even worse. This trend continued until the Great Famine in the 1840s.

There were big differences in wealth across the country. The north and east were more developed and involved in trade. But much of the west had few roads and a very simple economy. People there often didn't use money and relied heavily on potatoes for food.

Irish Politics and Power

Most people in Ireland were Catholic farmers. They were very poor and had almost no political power in the 1700s. Many Catholic leaders changed to Protestantism to avoid harsh punishments and keep their land.

There were two main Protestant groups. The Presbyterians in Ulster (the north) had better economic conditions but almost no political power. Real power was held by a small group of Anglo-Irish families who belonged to the Anglican Church of Ireland. They owned most of the farmland, which Catholic peasants worked. Many of these families lived in England and were loyal to England.

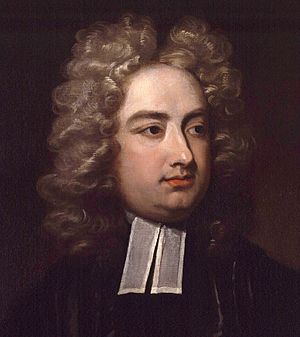

However, many Anglo-Irish who lived in Ireland started to feel more like Irish nationalists. They didn't like England controlling their island. Important speakers like Jonathan Swift and Edmund Burke wanted more local control for Ireland.

Ireland was a separate kingdom ruled by King George III of Britain. A law in 1720 said that Ireland depended on Britain and that the British Parliament could make laws for Ireland. The king controlled policy through his representative, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (also called the viceroy).

At first, viceroys often lived in England. Irish affairs were largely managed by a group of Irish Protestants called "undertakers." These men controlled the Irish Parliament and became very rich through their power.

Changes in Government

In 1767, a big change happened. An English politician named George Townshend became a very strong viceroy. Unlike others, he lived full-time in Dublin Castle. He had strong support from the king and his government in London. This meant that London made most major decisions.

Townshend ended the "undertaker" system and took control of power and jobs. His "Castle party" took charge of the Irish House of Commons. In response, a group called the "Patriots" rose up to challenge this strong, centralized government.

The Patriots, led by Henry Grattan, became much stronger after the American Revolution. They demanded more self-rule for Ireland. Their group, known as "Grattan's Parliament," forced Britain to change trade laws. They ended rules that stopped Ireland from trading with other British colonies.

The king and his government in London didn't want another revolution like in America. So, they made some agreements with the Patriots in Dublin. Mostly Protestant "Volunteer" groups of armed men were formed to protect Ireland from a possible French invasion. In Ireland, just like in America, the king no longer had complete control over armed forces.

As a result, new laws made the Irish Parliament a powerful body. It became independent of the British Parliament, though still under the King's watch. But these changes didn't satisfy the Irish Patriots; they just wanted more. The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was started by those who felt reforms were too slow. Britain put down the rebellion and officially joined Ireland with Britain in 1801. This included closing the Irish Parliament.

The Penal Laws Explained

The Irish Parliament during this time was almost entirely Protestant. Catholics had been stopped from holding public jobs in the early 1600s. They were banned from Parliament by the mid-1600s and lost their right to vote in 1727.

The defeat of Catholic supporters of King James II in the Williamite war in Ireland in 1691 was a huge blow. Those who fought for James II had their lands taken away. This war also meant Catholics were shut out of political power. Some Catholic landowners became Protestant to keep their land. Also, the Penal Laws said that Catholic-owned land could not be passed down to just one child. This made many Catholic landholdings less valuable and caused them to leave Catholic hands over time.

This period of defeat for Irish Catholics was called the long briseadh (meaning "shipwreck") in Irish language poetry. Protestant writings, however, celebrated the "Glorious Revolution." They saw it as bringing freedom from absolute rule and protecting property rights.

Presbyterians, who mostly lived in Ulster and were descended from Scottish settlers, also suffered from the Penal Laws. They could sit in Parliament but not hold public jobs. Both Catholics and Presbyterians were also banned from certain jobs (like law or the army). They also had limits on inheriting land. Catholics could not carry weapons or practice their religion openly.

In the early 1700s, these Penal Laws were strictly enforced. Protestants feared that Irish Catholic soldiers in the French army might try to bring back the old royal family. Sometimes, these fears grew because of Catholic bandits called rapparees and peasant secret groups like the Whiteboys.

However, after the Jacobite cause was finally defeated in Scotland in 1746, and the Pope recognized the British royal family in 1766, the threat to Protestant power lessened. Many Penal Laws were then relaxed or not strictly enforced. Some Catholic families even found ways around the laws by pretending to convert to Protestantism.

From 1766, Catholics wanted to reform the government in Ireland. Their views were shared by "Catholic Committees." These were moderate groups of Catholic landowners and religious leaders in each county. They asked for the Penal Laws to be removed and stressed their loyalty. Reforms on land ownership began in 1771 and again in 1778–79.

Grattan's Parliament and the Volunteers

By the late 1700s, many Irish Protestants saw Ireland as their home. They were angry that London often ignored Ireland. The Patriots, led by Henry Grattan, pushed for better trade rules with England. They especially wanted to end the Navigation Acts, which put taxes on Irish goods in English markets but allowed English goods into Ireland without taxes.

Irish politicians also wanted the Irish Parliament to be independent. They wanted to get rid of Poynings' Law, which allowed the English Parliament to make laws for Ireland. Many of their demands were met in 1782. Free trade was allowed between Ireland and England, and Poynings' Law was changed.

A key group in achieving these changes was the Irish Volunteers movement, started in Belfast in 1778. This group of armed citizens, up to 100,000 strong, was formed to defend Ireland from foreign invasion during the American Revolutionary War. But it was not controlled by the government. They held armed protests to support Grattan's reform plans.

For the "Patriots," the "Constitution of 1782" was the start of a new era. They hoped it would end religious unfairness and bring prosperity and self-government to Ireland. However, some conservative loyalists, like John Foster and John Fitzgibbon, were against giving more rights to Catholics. They argued that Protestant interests could only be safe if Ireland stayed connected to Britain.

Partly because trade laws were relaxed, Ireland had a strong economy in the 1780s. Canals were built from Dublin westward. Important buildings like the Four Courts and Post Office were established. Dublin's granite quays were built, and it was called the "second city of the empire." Laws were introduced in 1784 to encourage flour production, which helped mills and farming grow.

The United Irishmen and the 1798 Rebellion

More reforms for Catholics continued until 1793. They could then vote, serve on juries, and buy land. However, they still couldn't enter Parliament or become senior government officials. Reforms stopped because of the war with France (1793). But since the French republicans were against the Catholic Church, the government helped build St. Patrick's College in Maynooth for Catholic priests in 1795.

Some people in Ireland were inspired by the more radical French Revolution of 1789. In 1791, a small group of Protestant radicals formed the Society of the United Irishmen in Belfast. At first, they wanted to end religious discrimination and expand voting rights. But soon, the group became more radical. They wanted to overthrow British rule and create a republic where religion didn't matter.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, a leader of the United Irishmen, said their goals were to "use the common name of Irishman instead of Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter" and to "break the connection with England, the never-ending source of all our political problems."

The United Irishmen quickly grew across the country. Many Ulster Presbyterians liked the idea of a republic. They were educated, also faced religious discrimination, and had strong ties to Scots-Irish American immigrants who had fought against Britain in the American Revolution. Many Catholics, especially the growing Catholic middle class, also joined. By 1798, the movement claimed over 200,000 members.

The United Irishmen were banned after France declared war on Britain in 1793. They then changed from a political group into a military organization preparing for an armed rebellion. The Volunteer movement was also stopped.

However, these actions did not calm the situation in Ireland. These reforms were strongly opposed by "ultra-loyalist" Protestants like John Foster. Violence and disorder became common. Hardline Protestant attitudes led to the creation of the Orange Order, a strong Protestant group, in 1795.

The United Irishmen, now focused on armed revolution, joined forces with a militant Catholic peasant group called the Defenders. The Defenders had been raiding farmhouses since 1792. Wolfe Tone went to France to ask for French military help. The French sent an army of 15,000 troops that arrived off Bantry Bay in December 1796. But they failed to land due to bad decisions, poor sailing skills, and storms.

After this, the government started a harsh campaign against the United Irishmen. This included executions, torture, sending people to prison colonies, and burning houses. As the repression got worse, the United Irishmen decided to start their uprising without French help. This led to the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

When the main part of their plan, an uprising in Dublin, failed, the rebellion spread in different areas. It first appeared around Dublin, then briefly in Kildare, Meath, Carlow, and Wicklow. County Wexford in the southeast saw the most fighting. Rebels also rose up briefly in Antrim and Down in the north. A small French force landed in Killala Bay in County Mayo, leading to a final outbreak of rebellion in counties Mayo, Leitrim, and Longford.

The rebellion lasted only three months before it was put down. But it caused an estimated 30,000 deaths. Being the biggest outbreak of violence in modern Ireland, 1798 is a very important event in Irish memory.

The idea of a non-religious society was badly hurt by the violence between different religious groups during the rebellion. The British response was quick and harsh. Days after the rebellion started, local forces publicly executed suspected United Irishmen in Dunlavin and Carnew. Government troops and armed groups targeted Catholics. Rebels also sometimes killed Protestant loyalist civilians. In Ulster, the 1790s saw fighting between Catholic Defenders and Protestant groups like the Peep O'Day Boys and the new Orange Order.

Mostly because of the rebellion, Irish self-government was completely ended on January 1, 1801, by the Acts of Union 1800. The Irish Parliament, which was controlled by the Protestant landowners, was convinced to vote for its own closure. This was done out of fear of another rebellion and with the help of bribes from Lord Cornwallis, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. The Catholic Bishops, who had spoken out against the rebellion, supported the Union. They saw it as a step towards more rights for Catholics.

Culture and Arts

Some historians believe there were two main cultures in 18th-century Ireland that didn't mix much. One was Catholic and Gaelic (Irish-speaking), and the other was Anglo-Irish and Protestant.

During this time, there was still a lively Irish language literature. A good example is the Aisling (dream poem) style of Irish poetry. These poems often featured a woman representing Ireland. She would ask the young men of Ireland to save her from hardship. Many Irish language poets still felt a romantic connection to the Jacobite cause. However, some wrote in praise of the United Irishmen in the 1790s. Famous Gaelic poets from this time include Aogán Ó Rathaille and Brian Merriman.

Anglo-Irish writers were also very active. A notable one was Jonathan Swift, who wrote Gulliver's Travels. Edmund Burke, a political thinker, was important in the British Parliament and in the history of conservative ideas. One thinker who crossed the cultural divide was John Toland. He was an Irish-speaking Catholic from Donegal who became Protestant. He became a leading philosopher in intellectual circles across Europe.

Much of Ireland's beautiful city architecture also comes from this period, especially in Dublin and Limerick.

What Lasted From This Time

This period in Irish history has been called "the long peace." For almost 100 years, there was little political violence in Ireland, which was very different from the two centuries before. However, the period from 1691 to 1801 both began and ended with violence.

By its end, the power of the Protestant Ascendancy, which had ruled for 100 years, was starting to be challenged by a growing and more confident Catholic population. The period ended with the Acts of Union 1800, which created the United Kingdom in January 1801.

The violence of the 1790s shattered the hopes of many radicals that old religious divisions in Irish society could be forgotten. Presbyterians, in particular, largely stopped their alliance with Catholics and radicals in the 1800s. Under the leadership of Daniel O'Connell, Irish nationalism would later become more focused on Catholics. Many Protestants felt that their continued importance in Irish society and their hopes for the Irish economy could only be guaranteed by staying united with Britain. They became unionists.

|

See also

- Category:17th-century Irish people

- Category:18th-century Irish people

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |