Constitutional history of Canada facts for kids

The constitutional history of Canada is the story of how Canada's laws and government have changed over time. It all started in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris, when France gave most of New France to Great Britain. The colony of Canada, along the St. Lawrence River (now parts of Ontario and Quebec), saw many big changes in its government over the next century. In 1867, Canada became a new country called a Dominion, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Arctic oceans. Canada gained the power to make its own laws, separate from the United Kingdom, in 1931. Its constitution, which included a new rights charter, was fully brought home to Canada in 1982. Canada's constitution is a mix of all the important laws from this long history.

Contents

Treaty of Paris (1763)

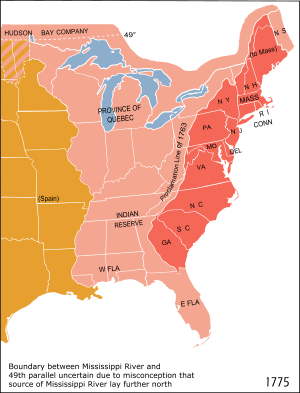

On February 10, 1763, France officially gave most of New France to Great Britain. The 1763 Treaty of Paris confirmed that Canada, including all its connected lands like Acadia (now Nova Scotia) and Cape Breton Island, now belonged to Great Britain. A year before, France had secretly given Louisiana to Spain to prevent Britain from taking it too. By the time the treaty was signed, the British army already controlled the French colony of Canada since 1760.

Royal Proclamation (1763)

Great Britain announced its plan for its new American colonies in a special announcement called the Royal Proclamation, issued on October 7, 1763. This proclamation changed Canada's name to "The Province of Quebec." It also set new borders and created a British-appointed government for the colony. This proclamation was like Quebec's constitution until the Quebec Act was passed later.

The new governor of the colony was given the power to create laws and set up courts. All British subjects in the colony were promised protection under English law. However, some parts of the Royal Proclamation went against agreements made when New France surrendered. For example, it made it hard for Catholics to hold government jobs, even though the French-speaking Canadians were mostly Catholic.

James Murray became the first civil governor of Quebec. He thought it was best to keep the French civil laws for a while. He hoped that over time, Canadians would choose to adopt British ways. But British merchants who had just moved to the colony were unhappy. They wanted British laws and a special assembly just for English-speaking Protestants. Murray didn't like these merchants and felt they were too extreme. They managed to get him called back to London, and Guy Carleton replaced him in 1768.

Calls for Change (1764–1774)

French-speaking Canadians quickly started asking for changes. In 1764, they asked for the king's orders to be available in French and for them to be allowed to join the government. By 1773, Canadian landowners asked for their old laws and customs to be fully restored. They also wanted the province's borders to be expanded back to what they were before.

Quebec Act (1774)

The Quebec Act, passed on June 13, 1774, granted many of the requests made by French-speaking Canadians. Here are the main changes:

- The borders of the Province of Quebec were greatly expanded, now covering the entire Great Lakes Basin.

- The freedom to practice the Catholic faith was confirmed. The Roman Catholic Church was officially recognized.

- Canadians no longer had to take a special oath that referred to Protestantism. This made it possible for them to hold positions in the colonial government.

- French civil law was fully brought back, while British criminal law was kept. This meant the old system of land ownership (seigneurial system) continued.

- No elected assembly was created, so the governor continued to rule with the help of his advisors.

British merchants in Quebec were not happy with this new act because it ignored their demands. They kept pushing for British civil law and an assembly that would exclude Catholics and French speakers. The Quebec Act was also very unpopular in the British colonies to the south, which later became the United States. This act was in place when the American Revolutionary War began in 1775.

Letters to the Inhabitants of Quebec (1774-1775)

During the American Revolution, the American Continental Congress tried to get the Canadian people to join their side. They wrote three letters, inviting Canadians to join the revolution. These letters talked about ideas like democratic government, the separation of powers, taxation power, and freedom of the press.

However, the Bishop of Quebec, Jean-Olivier Briand, told Canadians to ignore the "rebels" and defend their country and king. Even though both the British and the Americans tried to recruit Canadians for their armies, most people chose to stay out of the conflict.

Calls for Reform Continue (1784)

After the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the question of Canada's government came up again. In 1784, French merchant Pierre du Calvet published a document asking for constitutional reform. Later that year, two petitions asking for an elected assembly were sent to the king. One was signed by French-speaking Canadians, and the other by British settlers.

At this time, many United Empire Loyalists (people who stayed loyal to Britain during the American Revolution) were moving to Quebec and Nova Scotia. These new settlers also wanted quick changes to the government.

Constitutional Act (1791)

On June 10, 1791, the Constitutional Act was passed in London. This act gave Canada its first parliamentary government. It made the following important changes:

- The Province of Quebec was divided into two separate provinces: Lower Canada (now Quebec) and Upper Canada (now Ontario).

- Each province received an elected Legislative Assembly, an appointed Legislative Council, and an appointed Executive Council.

- The governor had the power to appoint the speaker of the Legislative Assembly and approve or reject new laws.

- Land was set aside for Protestant churches in each province.

This division made sure that the Loyalists would be the majority in Upper Canada, allowing British laws to be used there. In Lower Canada, French civil law and English criminal law continued to exist side-by-side.

While this new constitution solved some immediate problems, it also created new political challenges. One major issue was that the elected Legislative Assemblies did not have full control over the provinces' money. Also, the appointed Executive and Legislative Councils were not truly answerable to the elected assembly. This led to a movement for reform in both provinces.

Union Bill (1822)

In 1822, British officials secretly proposed a bill to unite the two Canadian provinces. This news caused a strong reaction in Lower Canada. The bill suggested that each part of the new united province would have an equal number of representatives. This would have made the French-speaking majority in Lower Canada a minority in the new Parliament.

People in both Lower and Upper Canada protested. In January 1823, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada sent a delegation to London to present their strong opposition. They had a petition with about 60,000 signatures. Because of this widespread opposition, the British government dropped the plan to unite the provinces.

Calls for Responsible Government (1834-1837)

In 1834, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada passed the Ninety-Two Resolutions. These were a list of demands, asking for more democratic control over the government. They wanted elected representatives to have more power. However, the British government's response, known as the Russell Resolutions in 1837, rejected most of these demands. They even took away the assembly's power to control its own budget.

This rejection caused a lot of tension, leading to armed rebellions in Lower Canada in 1837 and 1838, known as the Lower Canada Rebellion. British troops quickly put down these uprisings. The Catholic Church also played a role in stopping the rebellion, telling its followers that questioning authority was a sin.

Lord Durham's Report (1839)

After the rebellions, the British government sent Lord Durham to investigate. His report suggested uniting Upper and Lower Canada. He believed this would help French-speaking Canadians become more like the English population, which he thought would prevent future conflicts.

Act of Union (1840)

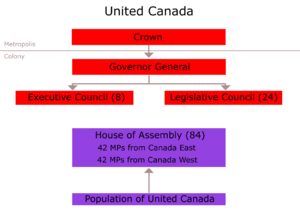

Following Lord Durham's report, the British Parliament passed the Act of Union in June 1840. This act combined Upper Canada and Lower Canada into a single province called the Province of Canada. The main changes were:

- The two provinces were united into one.

- Their separate parliaments were replaced by a single Parliament of Canada.

- Each of the two former sections (now Canada East and Canada West) had an equal number of elected representatives.

- Electoral districts were redrawn to give more representation to the former Upper Canada.

- Candidates for elections had to own land worth at least 500 pounds.

- All official documents and laws had to be in English only.

This union meant that French was banned in the legislature for about eight years. The French-speaking majority of Lower Canada became a political minority in the new unified Canada. This gave English speakers more political control. However, constant disagreements between English and French representatives led to a desire for a different type of government, which eventually led to Canadian Confederation.

Responsible Government (1848)

A major goal for politicians in both Canada East and Canada West was to achieve "ministerial responsibility." This meant that the government's leaders (the Executive Council) should be chosen from the elected members of the assembly and be accountable to them. This finally happened in 1848 when Governor Lord Elgin allowed Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin, leaders of the majority parties, to form their own Executive Council. This made the Province of Canada's government similar to that of Great Britain.

British North America Act (1867)

The British North America Act 1867 was the law that created the Dominion of Canada. It brought together the British colonies of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The former parts of Canada were renamed Ontario (from Canada West) and Quebec (from Canada East). Quebec and Ontario were given the same standing as New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the new Parliament of Canada. This was done partly to protect British lands from American expansion.

Before 1867, the colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island had discussed joining together. The Province of Canada joined these talks at Britain's request. These discussions led to the creation of Canada. The first constitutional conference was held in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Newfoundland also participated in later talks but decided not to join at that time.

Province of Manitoba (1870)

On May 12, 1870, the British Crown officially created the province of Manitoba through the Manitoba Act. This act set the province's borders, voting rights, and how many representatives it would have in the Canadian Parliament. It also allowed the use of both English and French in the provincial Parliament and courts, and permitted separate school systems for different religions. This was done because Manitoba had both French-speaking Catholic communities (the Métis) and English-speaking Protestant communities.

Statute of Westminster (1931)

The Statute of Westminster 1931 was a very important law. It gave Canada and other British dominions full power to make their own laws. Before this, some Canadian laws still needed approval from the British Parliament. However, the British North America Acts (Canada's constitution) were still an exception and could only be changed by the British Parliament until 1982.

The Quiet Revolution (1960s)

In the early 1960s, Quebec experienced a period of rapid change called the Quiet Revolution. French-speaking Quebecers felt a new sense of identity and wanted more control over their own affairs. The new provincial government, led by Jean Lesage, modernized government institutions, took control of electricity production, and encouraged unions. These changes aimed to redefine the relationship between French-speaking Quebecers and the mostly English-speaking business class. This period also saw a rise in support for Quebec independence.

Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963)

The federal government was concerned by Quebec's demands for more power. In 1967, a meeting of all provincial premiers and the prime minister was held to discuss Canada's future. They looked at recommendations from a commission on bilingualism (two languages) and biculturalism (two cultures), and discussed a Charter of Rights.

In 1968, René Lévesque's movement for Quebec sovereignty joined with other groups to create the Parti Québécois, a provincial political party that supports Quebec's independence. That same year, Pierre Trudeau became prime minister of Canada. He worked to improve Quebec's place within Canada, including passing the Official Languages Act in 1969. This law made both French and English official languages across Canada, building on their status from the 1867 British North America Act.

Victoria Charter (1971)

In 1971, the federal government and the provinces met and created the Victoria Charter. This charter tried to find a way to change the Constitution without needing every province to agree. It would have given a veto (the power to block a decision) to any province that had, or had ever had, 25 percent of Canada's population. This would have given Quebec and Ontario veto powers. However, the charter failed because not all provinces confirmed their agreement.

Referendum on Sovereignty-Association (1980)

In 1976, the Parti Québécois won the provincial election in Quebec. In the 1980 Quebec referendum, the Parti Québécois asked the people of Quebec for permission to negotiate a new relationship with the rest of Canada, called "sovereignty-association." Even with a high voter turnout, 60 percent of Quebec voters rejected the idea.

After the referendum, Quebec's government stated that a lasting solution to constitutional issues needed to recognize that Canada has two main cultures or "nations." They also said Quebec would not agree to bring the Constitution home to Canada unless it was guaranteed all the powers it needed for its development. Because of this, Quebec's government refused to approve the new Canadian constitution a year later. While this was a symbolic act, it did not stop the Canadian Constitution from applying in Quebec.

Quebec's government made specific demands, such as control over its highest court, language and education, economic development, and most forms of taxation. Many Canadians felt these demands would make the federal government too weak. However, some believed these changes were good, as Quebec politicians would be more in tune with Quebecers' needs.

Patriation: Canada Act (1982)

After the 1980 referendum, the federal government and all provincial governments, except Quebec, agreed that Canada should take full control of its own constitution. This had previously been the responsibility of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This agreement was passed as the Canada Act 1982 by the British Parliament and became law on April 17, 1982. In Canada, this was called the patriation of the Constitution.

This action, which included creating a new Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, was led by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. He wanted to create a multicultural and bilingual society across Canada. Many Quebecers felt this was not enough, as Quebec already had its own charter of rights since 1975. They wanted to protect French within Quebec, not necessarily impose it elsewhere. Many Canadians believe Quebec is unique but should not have more power than other provinces.

The government of Quebec objected to the 1982 constitutional changes because the new way to amend the constitution did not give Quebec veto power over all changes. Many in Quebec felt that the other provinces adopting the amendment without Quebec's agreement was a betrayal. They called it the "Night of the Long Knives." Despite Quebec's disagreement, the constitution still applies within Quebec.

Constitutional Reform and Upheaval (1982 onwards)

Since Canada's constitution was brought home without Quebec's consent, later efforts tried to improve the situation. Two formal attempts to change the constitution failed. A very close sovereignty referendum in 1995 shook Canada and led to the Clarity Act.

Meech Lake Accord (1989)

In 1987, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney tried to address Quebec's concerns and bring the province into an amended constitution. Quebec's provincial government, which wanted to stay in Canada under certain conditions, supported the agreement, called the Meech Lake Accord. However, the accord failed because not all provinces approved it in time.

After the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990, some Quebec politicians from the ruling parties formed the Bloc Québécois. This new federal political party aimed to defend Quebecers' interests and work towards independence.

Referendum on Charlottetown Accord (1992)

In 1992, the federal government, all provincial and territorial governments, and four Indigenous groups negotiated a second proposed constitutional agreement called the Charlottetown Accord. Even though most political leaders supported it, this effort was rejected in a nationwide referendum in October 1992. In Quebec, 57 percent opposed the accord, seeing it as a step backward compared to the Meech Lake Accord.

Referendum on Sovereignty (1995)

A referendum held in Quebec on October 30, 1995, asked Quebecers if they wanted to become a sovereign (independent) country. The vote was very close, with 50.56% voting against sovereignty and 49.44% voting for it. Voter turnout was very high at 93%.

Clarity Act (1998)

After the close 1995 referendum, Prime Minister Chrétien asked the Supreme Court of Canada for its opinion on how a province could separate. The Court ruled that Quebec could not unilaterally separate and that a referendum would need a clear majority in favor of a clearly worded question.

Following this decision, the federal government introduced the Clarity Act. This law set guidelines for any future provincial referendum on separation. It stated that the federal government would decide if the question was clear and if a "clear majority" was achieved. Supporters of Quebec sovereignty argue that this law gives the federal government veto power over referendums on sovereignty. Both houses of Parliament approved the legislation, with only members of the Bloc Québécois opposing it.

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |