Discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun facts for kids

The tomb of Tutankhamun was found in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. An Egyptologist named Howard Carter led the team that discovered it. This happened more than 3,300 years after Tutankhamun's death. Most pharaohs' tombs were robbed long ago. But Tutankhamun's tomb was hidden by rocks and dirt. This kept it safe from robbers. It was the first royal tomb from ancient Egypt found mostly untouched. Many people still call this one of the most famous archaeological finds ever.

Carter and his rich supporter, Lord Carnarvon, opened the tomb on November 4, 1922. They found over five thousand objects inside. Many of these items were very old and fragile. It took a huge effort to carefully remove them. The amazing treasures caused a lot of excitement in the news. They also made ancient Egyptian styles popular in Western countries. For Egyptians, who had recently gained some freedom from British rule, the tomb became a symbol of national pride. This helped an idea called Pharaonism grow stronger. It linked modern Egypt to its ancient past. This also caused some arguments between Egyptians and the British-led team. The news about the tomb grew even bigger when Lord Carnarvon died from an infection. People started to wonder if his death was caused by an ancient curse.

After Lord Carnarvon died, Carter and the Egyptian government argued over who controlled the tomb. In early 1924, Carter stopped working to protest. This argument lasted until the end of the year. They finally agreed that the treasures would not be split between the government and the dig's funders. This was a common practice before. Instead, most of the tomb's items went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In later years, news interest faded. Only the removal of Tutankhamun's mummy from its coffin in 1925 got much attention. The last two rooms of the tomb were cleared from 1926 to 1930. The final treasures were sent to Cairo in 1932.

The tomb's discovery did not teach Egyptologists much new history about Tutankhamun's time. But it did confirm how long he ruled. It also gave clues about the end of the Amarna Period. This was a time of big changes before his rule. The tomb taught more about the daily life and objects of Tutankhamun's era. It showed what a complete royal burial looked like. It also gave proof about how rich Egyptians lived and how ancient tomb robbers behaved. The excitement from the find also helped train more Egyptians in Egyptology. Since its discovery, the Egyptian government has used the tomb's fame. They send exhibitions of the treasures around the world. This helps raise money and build good relationships with other countries. Tutankhamun has become a symbol of ancient Egypt itself.

Finding the Tomb

Tutankhamun's Burial

The pharaoh Tutankhamun ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty. This was part of the New Kingdom. He died around 1323 BC. He was buried in the Valley of the Kings, near Thebes (now Luxor). Most New Kingdom rulers were buried there. His tomb was small, dug into the valley floor. It was likely a private tomb made bigger for a king's burial.

The tomb was robbed twice soon after it was built. Officials fixed and resealed it. They filled the entrance with limestone chips to stop more robbers. About 200 years later, during the reigns of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, their tomb was built. Debris from this building covered Tutankhamun's tomb. This hid it from later robbers. So, unlike other tombs in the valley, most of its treasures stayed inside.

Searching the Valley of the Kings

In the early 1900s, Egypt was controlled by the British. The study of ancient Egypt, called Egyptology, was managed by the Antiquities Service. New digs were often funded by museums or rich collectors. In return, they usually got half of the items found. The other half went to the Antiquities Service and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Many tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been open since ancient times. Many others were found in the 1800s. Some royal mummies and burial items were found. But no complete set of royal burial goods had ever been discovered.

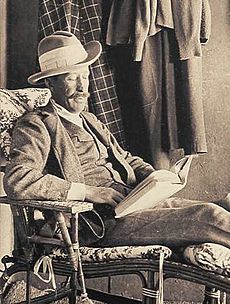

Howard Carter became an inspector for the Antiquities Service in 1900. He worked in Upper Egypt, including the Valley of the Kings. Carter had first come to Egypt as an artist. He helped record art in Egyptian tombs. Then he trained as an archaeologist. As inspector, Carter worked to protect and restore open tombs. He also looked for undiscovered tombs. He found a supporter in Theodore M. Davis, a rich American. With Davis's help, Carter made some small finds. He also cleared three tombs that had not been explored before.

Davis continued to dig in the valley for ten more years. He pushed his excavators to work fast. They nearly doubled the number of known tombs. But his finds were often not handled carefully or recorded well. Davis thought that almost all kings' tombs in the valley had been found. In 1912, he wrote: "I fear the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted."

Carter's Final Search

Carter left the Antiquities Service in 1905. He then worked for George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, who collected Egyptian items. Carnarvon bought the right to dig in the Valley of the Kings in 1914. The First World War made digging hard. But in 1917, Carter began to clear the valley down to the rock. This meant sifting through old dirt piles from earlier digs. It also meant clearing natural dirt from floods. At this time, Carter and Carnarvon did not say they were looking for Tutankhamun's tomb. But they had reasons to think it was still hidden.

Egypt's political situation changed a lot during these digs. The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 led to Egypt's independence in February 1922. But the United Kingdom still had a lot of power. The Antiquities Service now answered to an Egyptian minister.

The digging season in Egypt is from November to April. In mid-1922, only one part of the Valley of the Kings was still covered in debris. This area was hard to clear. It had old workers' huts and was near a busy tourist spot. Carnarvon thought about stopping the dig. But Carter offered to pay for clearing this last section himself. Carnarvon was impressed and agreed to fund one more season.

Discovery and Clearing the Tomb

The First Season

Finding the Tomb

Carter and his Egyptian workers started digging on November 1, 1922. This was earlier than usual. On November 4, a worker found a step in the rock. This step was the start of a staircase leading to a tomb. At the bottom was a sealed doorway. Carter cut a small hole and looked inside. He saw that the passage beyond was filled with rubble. Carter sent a telegram to Carnarvon, who was in England. He had the workers refill the pit to keep the tomb safe.

Carnarvon arrived in Luxor on November 23 with his daughter, Evelyn Herbert. The digging started again. They looked closer at the doorway seal. It had Tutankhamun's name on it. This suggested it was his tomb. The passage rubble had items with other kings' names. This hinted it might be a mix of objects buried during his rule. The doorway had been partly broken before being resealed. This showed an ancient robbery had happened. On November 26, the team reached another sealed doorway. Carter wrote about opening it in a famous passage:

"With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space... showed that whatever lay beyond was empty... I inserted the candle and peered in... At first I could see nothing... but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold."

Carnarvon asked Carter what he saw. Carter's most famous reply was: "Yes, wonderful things."

Starting the Clearance

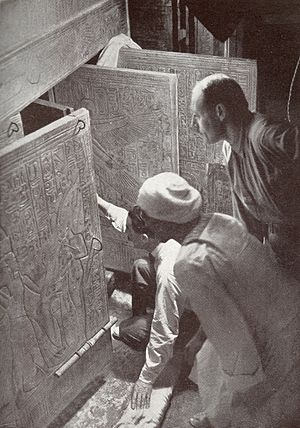

The gold-covered furniture and statues Carter saw were in a room called the antechamber. This room alone held more treasures than anyone expected. Some items were familiar, some were very fancy, and some were completely new. Two doorways led from the antechamber. They had been blocked and then broken by ancient robbers. One led to a room called the annexe, filled with a messy pile of objects. The other had been resealed long ago. Many items had Tutankhamun's name. This confirmed it was his original burial place.

Later, the excavators broke through the sealed doorway. Carter, Carnarvon, and Evelyn Herbert squeezed through. They found the burial chamber. It was mostly filled with gold-covered shrines. These shrines held Tutankhamun's sarcophagus. The robbers had not gone past the first shrine.

Clearing the tomb would be a huge job. Water from flash floods had seeped into the tomb over centuries. This caused wood to warp, glue to dissolve, and fabrics to rot. Every surface had a pink film. Carter believed that without careful restoration, only a small part of the treasures would survive moving them to Cairo. He asked for help from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They sent experts like Arthur Cruttenden Mace for conservation, Harry Burton for photography, and Alfred Lucas for chemistry. They used other tombs nearby as a lab, darkroom, and dining area. Four Egyptian foremen and porters also worked hard to move the items.

On December 16, they began clearing the antechamber. Objects were labeled and photographed before being moved. Carter said the items were so crowded it was hard to move one without damaging others. Some were so tangled they needed special supports. Disorganized box contents had to be sorted. Pieces of one object might be found in different spots. After removal, items were cleaned and treated with preservatives.

"Tutmania"

The tomb caused a public craze called "Tutmania." This was part of a larger interest in ancient Egypt called Western Egyptomania. News of the discovery spread quickly. Carter and Carnarvon became famous worldwide. Tutankhamun, who was unknown before, became known as "King Tut."

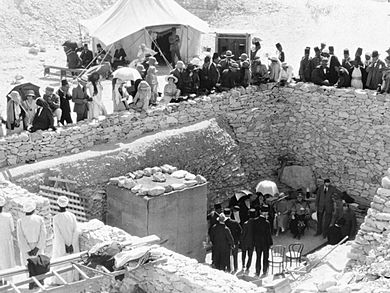

Tourists in Luxor flocked to the tomb. They crowded around the wall that surrounded the entrance. Sometimes, the excavators left objects uncovered when carrying them out. This was to please the onlookers. Many important people demanded to enter the tomb. This made the work harder and risked damaging the treasures.

The excitement went beyond the tomb. Hotels played the "Tutankhamun Rag." In the United States, the discovery inspired movies and a hit song, "Old King Tut." Interest in Egyptology and sales of books about ancient Egypt also grew.

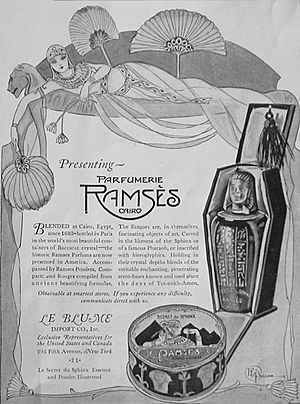

The rich treasures especially caught public attention. Replicas appeared as early as 1924. Clothes, jewelry, and furniture were made with Egyptian designs. Some were based on real items from the tomb. Others just used ancient Egyptian names and styles. These "Tutmania" products were made for everyone, not just the rich.

In the early 1900s, Egyptians started to see ancient Egypt as a source of national identity. This idea was called Pharaonism. It united Egyptians and showed that Egypt was once powerful. Tutankhamun became a national symbol. Ancient images appeared everywhere in Egyptian newspapers. Ancient Egypt became a common topic for plays and novels.

Carnarvon wanted to use the publicity to help pay for the dig. He signed a deal with The Times newspaper. This gave their reporter, Arthur Merton, special access to the tomb. Other newspapers were angry about this. Their stories about Carnarvon became more negative. Egyptian papers also criticized the deal. They saw it as a sign of continued foreign control. Egyptians also worried that the treasures would be divided. They feared many items would leave the country.

The "Curse of Tutankhamun"

The antechamber was almost empty by mid-February. On February 16, Carter and Carnarvon officially opened the burial chamber. Government officials were there. At one end of the burial chamber was an open doorway to a fourth room, called the treasury. It held the canopic chest with Tutankhamun's preserved organs. Carter boarded up this entrance. It was not reopened until 1927.

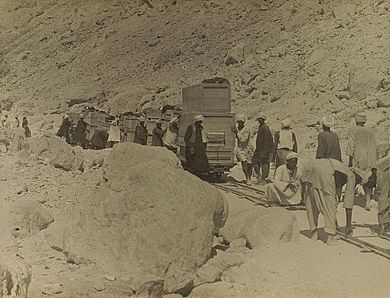

The tomb was closed for the season on February 26. Workers reburied the entrance to prevent anyone from getting in. Conserved objects were packed up. Workers pushed them by hand along a Decauville railway track to the Nile River. From there, the items were shipped to Cairo.

Soon after the tomb closed, Carnarvon accidentally cut a mosquito bite while shaving. The wound got infected. After weeks of illness, he died on April 5. Carnarvon had been sick for twenty years. But his death quickly led to talk of something more than just illness.

Stories about Egyptian spirits or mummies taking revenge on those who disturbed their tombs had been around since the late 1800s. This idea became known as the "mummy's curse." Now, this idea was linked to Carnarvon's death.

Some people claimed they had warned Carnarvon of danger before he died. A former Egyptologist, Arthur Weigall, said he joked that Carnarvon would die in six weeks if he entered the tomb in a joking spirit. Some later stories claimed an ancient text wishing death on tomb violators was written on the doorway. But no such curse has ever been found in Tutankhamun's tomb.

Any deaths or strange events linked to the tomb were blamed on the curse. Carnarvon's son said Cairo had a power outage when his father died. He also said his father's dog howled and died in England. Another story involved Carter's canary. A cobra entered Carter's house and ate the bird. Egyptians called this a bad sign. They linked the cobra to the uraeus, the protective cobra on Tutankhamun's statues. Many other deaths were also linked to the curse. But most Egyptologists did not believe these claims. A study in 2002 found no real difference in death rates between those who entered the tomb and those who did not.

Egyptian writers also used the curse idea. They wrote funny stories where Tutankhamun woke up to comment on current politics. More serious stories showed mummies facing Westerners who disturbed their tombs. These stories showed mummies not as scary monsters, but as national ancestors. They sought to fix how foreign powers treated Egypt's heritage.

The Second Season

Between digging seasons, Carter and Mace wrote the first book about the discovery. It was published in October as Carter returned to Egypt. After Carnarvon's death, his wife, Almina Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, paid for the tomb clearance. Carter now spoke for the team to the government and the press.

Entering the Burial Chamber

The season began with moving two life-size statues of Tutankhamun from the antechamber. Then, the team started to remove the sarcophagus shrines. This was hard because the shrines filled most of the burial chamber. There was little room to move. Part of the wall between the antechamber and burial chamber had to be taken down. This gave workers more space. Scaffolding was built to take the shrines apart from the top.

Arguments grew between the excavators and the Antiquities Service. Carter wanted to limit visitors to the tomb strictly. The head of the Antiquities Service, Pierre Lacau, required an inspector on site. He also demanded a list of all Carter's workers. This rule is common now but was new then. It was aimed at Merton, the newspaper reporter.

Lacau also brought up the "division of finds." In 1922, Lacau had said that excavators would no longer get half of the finds. All ancient items in Egypt belonged to the government. This change did not apply to Carnarvon's existing agreement. That agreement allowed for a division of finds, unless the tomb was completely untouched. Carnarvon had planned to argue that Tutankhamun's tomb was not untouched because it had been robbed. He expected to get some items. Lacau now suggested that all items belonged to the Egyptian government. This meant no division of finds.

Other Egyptologists worried that Lacau's rules would hurt their work. They sent a letter of protest. They said the Tutankhamun discovery belonged "not to Egypt alone but to the entire world." This made political tensions worse. Egyptian elections in January 1924 brought a nationalist government to power. The letter went to the new minister of public works, Morcos Bey Hanna. He was not friendly to Britons.

Once the shrines were taken apart, the excavators used pulleys to lift the stone sarcophagus lid. This was a very careful job because the lid was cracked. On February 12, the lid was lifted. Under a cloth, they saw a gold-covered wooden coffin. It was shaped like a human and had Tutankhamun's face. This was the first complete set of royal coffins ever found. Its beauty and good condition amazed everyone.

Strike and Lawsuit

A viewing of the coffin for the Egyptian press was set for February 13. Then, a tour for the excavators' wives and families was planned. Hanna saw this tour as an insult. He noted that wives of Egyptian ministers had not been allowed in the tomb. So, he forbade the families' visit. He sent police to ensure his order was followed. Carter and his team were very angry. They announced they were stopping work. They called the government's rules "impossible restrictions." Carter locked the tomb. Hanna ended the Carnarvon agreement. Lacau brought workers to saw off Carter's locks. The government held a big event at the tomb to celebrate its reopening.

British officials attended the reopening. This showed that the British government would not support Carter. Still, Carter sued the Antiquities Service. He used Carnarvon's lawyer, F. M. Maxwell. This was a bad choice. Maxwell had been the prosecutor in Hanna's treason trial. In March, Maxwell said in court that the government had seized the tomb "like a bandit." This word caused riots in Cairo. The court first sided with Carter. But Hanna took the case to a higher court. On March 31, that court fully supported Hanna's actions.

Carter left Egypt on March 21 for a lecture tour. His absence eased tensions. The political situation in Egypt changed again on November 19, 1924. A British official was killed by nationalists. The British reacted strongly. The Egyptian prime minister resigned. A new, more pro-British government was formed. This government reached an agreement about the tomb. Carter would continue to oversee the clearance. Lady Carnarvon would fund it but gave up her claim to a share of the treasures. The newspaper's special access ended. Carter resumed work on January 25, 1925.

Later Seasons

Work Continues and Tutankhamun's Burial

The third season was short and quiet. The excavators only worked to conserve objects already in the lab tomb. News interest quickly dropped. Coverage only flared up when Tutankhamun's mummy was unwrapped. The rest of the clearance happened away from the media.

The fourth season began in late 1925. It focused on Tutankhamun's burial itself. His mummy lay inside three nested coffins. The innermost one was made of about 110 kg (243 lb) of solid gold. On his body and in his mummy wrappings, the king wore many jewels and other items. This included a gold burial mask. The inner coffin and mummy were covered in sticky oils from the burial. These oils had hardened, gluing the mummy and its items to the bottom of the inner coffin. That coffin was also stuck to the middle coffin. The oils had also turned the linen wrappings and some of the mummy's tissues into carbon. This made Tutankhamun's body very fragile.

The excavators tried to melt the resin by heating the coffins in the sun. This did not work. So, Tutankhamun's remains were still in the coffins when anatomists Douglas Derry and Saleh Bey Hamdi began examining them on November 11, 1925. Over eight days, they carefully chiseled the pieces out of the resin. They removed the burial goods as they went.

After the examination, the excavators separated the coffins. They built supports to hang the stuck-together coffins upside down. They placed lamps underneath to heat them to 500°C (932°F). They shielded the coffins from the heat with wet blankets and zinc plates. Once the coffins were apart, the remaining resin was cleaned with solvents.

Treasury, Annexe, and Completion

In the fifth season, Carter rearranged the mummy pieces to look whole again. He placed them in the outermost coffin. He covered the sarcophagus with a glass plate instead of the original lid. Then, the excavators opened the treasury. They sorted through its contents. This included a shrine of the god Anubis, more boxes of jewelry, wooden tomb models of boats, and the canopic chest. This chest held the organs removed from Tutankhamun's body during embalming. The most unexpected items were the mummies of two fetuses. These are thought to be Tutankhamun's stillborn children.

In early 1927, Carter published the second book about the tomb. In the next season, the excavators faced the annexe. This room held more than half of all the items in the tomb. The floor was completely covered with randomly piled burial goods. It was almost a meter (3 feet) below the antechamber floor. To start work, one man had to lean through the doorway at a difficult angle. Others in the antechamber supported him with slings. The last object was removed from the annexe on December 15. The rest of the season was spent on conservation.

Little was done in the sixth season because Lucas and Burton were sick. The seventh season had more arguments between Carter and the authorities. The Carnarvon agreement ended in 1929. Ownership of the tomb went back to the Egyptian government. Egyptian law said only government workers could have keys to government property. Carter did not like having to rely on an inspector to open the tomb each day. In early 1930, the government made a final deal with Lady Carnarvon. They paid her for the dig's costs.

The last challenge was conserving the dismantled shrine pieces. They were still stacked in the antechamber. The last shrine pieces were removed from the tomb in November 1930. Conservation of objects continued until February 1932. Then, the last burial goods were sent to Cairo.

What Happened to the Treasures?

There were 5,398 distinct objects found in the tomb. Carter estimated that only a tiny fraction were too damaged to fix. Most of the rest went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. They now make up about one-sixth of the museum's permanent displays. The sarcophagus, outermost coffin, and mummy stayed in the burial chamber. A skullcap and a large beaded collar also remained. Carter thought these were too fragile to move from the mummy.

People often say the clearance was very careful and organized. Jason Thompson, who wrote a history of Egyptology, calls Carter one of the best archaeologists in Egypt at that time. He says if the tomb had been found earlier, the clearance would have been much worse. However, Carter did give some small objects to visitors or other Egyptologists. These items sometimes ended up in museum collections. For example, Gardiner had an argument with Carter in 1934. He realized an amulet Carter gave him had been stolen from the tomb.

After Carter died in 1939, his niece found several such objects among his things. She had them returned to Egypt. In 1978, Thomas Hoving, a former museum curator, pointed out items in the Metropolitan Museum's collection. He thought they likely came from the tomb. The museum gave several of these items to the Egyptian government in 2010.

Recording the Finds

The final book about the tomb, covering the treasury and annexe, was published in 1933. But these three books were for the public. They were not a full archaeological report. The clearance produced a lot of records. Almost every object was listed. Most were photographed by Burton. Several experts wrote special reports. Carter hoped to put all this material into a formal Egyptology report. But he died before he could start.

Soon after Carter's death, his niece gave his journals and notes to the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford. In the 1990s, the institute started scanning these materials. They made them available online in the early 2010s.

The Tomb's Impact

When the tomb was found, Egyptologists hoped it would have documents. They wanted to learn more about Tutankhamun's time. No such documents were found. But the items did give clues. Dates on wine jars showed Tutankhamun ruled for no more than nine years. Egyptologists had thought he was an old courtier. But examining his mummy showed he was 17 to 22 years old when he died. The unusual shape of his skull was like another royal mummy. This suggested he was related and had royal blood. Some art from the tomb is in the Amarna Period art style. Some items mention the Aten, a god worshipped in that period. This shows that the return to older traditions during Tutankhamun's rule happened slowly.

Much of the tomb's historical value came from the burial goods. They included beautiful examples of ancient Egyptian art. They helped us understand the daily life and objects of the New Kingdom. For example, many clothes from the tomb are more varied and decorated than those shown in art from that time. The tomb also gives great proof about tomb robbery and official efforts to fix them. Because most items were still there, it is possible to guess what was stolen and what was put back.

The discovery changed the history of the Valley of the Kings. After the clearance, many Egyptologists lost interest. They thought there was nothing left to find. Little archaeological work happened there for decades. No new tombs were found until KV63 in 2006.

The discovery also affected Egyptology in another way. Along with Egypt's new independence, the excitement about Tutankhamun helped Egyptian Egyptology grow. When the tomb was found, very few Egyptians were trained in archaeology. Hamdi was the only Egyptian expert who worked on the tomb. The first Egyptian university program for Egyptology started in 1924. Over the next ten years, a new group of Egyptian Egyptologists was trained.

Western public interest in Tutankhamun faded for over thirty years. But it came back when the Egyptian government started sending the treasures on international museum exhibitions. These shows began in the early 1960s. They aimed to get Western support to move ancient Egyptian monuments. These monuments were in danger of being flooded by the Aswan High Dam. The exhibitions were very popular. The one that toured the United States in the 1970s drew over eight million visitors. It changed how American museums operated. They started focusing on big, profitable exhibitions. Much of the money from the exhibitions helped move the monuments. It also paid for improvements to the Egyptian Museum. The exhibitions also helped Egypt's relationships with other countries.

Today, the discovery is still the most famous find in the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun is the best-known ruler of ancient Egypt. It is also seen as one of the greatest archaeological discoveries. Thanks to his fame, Tutankhamun "has been reborn as Egypt's most famous son." The tomb and its treasures are key attractions for Egypt's tourist industry. They are also a source of pride for the Egyptian people.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |