Ramesses VI facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ramesses VI |

|

|---|---|

| Ramses VI, Rameses VI, Ramesses VI Amunherkhepeshef C | |

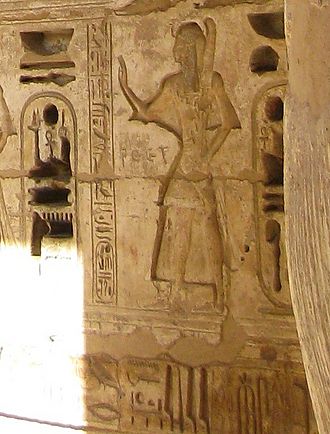

Fragment of Ramesses VI's stone sarcophagus from his tomb now on display at the British Museum. The sarcophagus was originally painted, its stone quarried in the Wadi Hammamat.

|

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | 8 regnal years Eight full years and two months in the mid-to-late 12th century BC (20th Dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Ramesses V |

| Successor | Ramesses VII |

| Consort | Nubkhesbed |

| Children | Iset ♀, Ramesses VII ♂, Amenherkhepshef ♂, Panebenkemyt ♂ uncertain: Ramesses IX ♂ |

| Father | Ramesses III |

| Mother | Iset Ta-Hemdjert |

| Died | in his 40s |

| Burial | KV9; Mummy found in the KV35 royal cache (Theban Necropolis) |

Ramesses VI Nebmaatre-Meryamun was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh. He was the fifth ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled for about eight years in the mid-to-late 12th century BC. Ramesses VI was the son of Ramesses III and Queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert. Before becoming king, he was known as Prince Amenherkhepeshef. He held important titles like royal scribe and cavalry general. His son, Ramesses VII, whom he had with Queen Nubkhesbed, became king after him.

Ramesses VI became pharaoh after Ramesses V died. Ramesses V was the son of Ramesses VI's older brother, Ramesses IV. In his first two years as king, Ramesses VI stopped attacks by Libyan or Egyptian groups in Upper Egypt. He also buried his predecessor, Ramesses V, in a tomb that is now lost. Ramesses VI took over KV9, a tomb in the Valley of the Kings that was meant for Ramesses V. He made it bigger and redecorated it for himself. The huts of the workers near the entrance of KV9 actually covered the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb. This helped save Tutankhamun's tomb from robbers for many years.

During Ramesses VI's rule, Egypt lost control of its last strongholds in Canaan. Even though Egypt still controlled Nubia, losing the lands in Asia made Egypt's economy weaker. Prices went up. It became harder to pay for building projects. So, Ramesses VI often carved his own name over the names of earlier pharaohs on their monuments. He still claimed to have "covered all the land with great monuments in my name." He also liked having statues made of himself. More statues of him exist than of any other king from the Twentieth Dynasty after Ramesses III.

The pharaoh's power in Upper Egypt became weaker during Ramesses VI's time. His daughter Iset was named God's Wife of Amun. However, the High Priest of Amun, Ramessesnakht, made Thebes a very important religious center. It became almost as powerful as Pi-Ramesses in Lower Egypt, where the pharaoh lived. Even with these changes, there is no sign that Ramessesnakht's family worked against the king. This suggests that the kings might have approved of these changes. Ramesses VI died in his forties, in his eighth or ninth year as king. His mummy was found in his tomb, but it was damaged by robbers. Later, his body was moved to KV35. It was discovered in 1898 by Victor Loret. Today, his mummy is kept in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

Contents

Ramesses VI's Family Life

Who Were Ramesses VI's Parents?

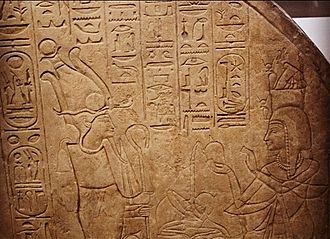

Ramesses VI was the son of Ramesses III. Ramesses III is thought to be the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom of Egypt. We know this from a large carving at the Medinet Habu temple of Ramesses III. This carving is called the "Procession of the Princes." It shows ten princes, including Ramesses VI, honoring their father. The carving was likely made when Ramesses VI was a young prince. He is shown with a sidelock of youth, which was a hairstyle for children.

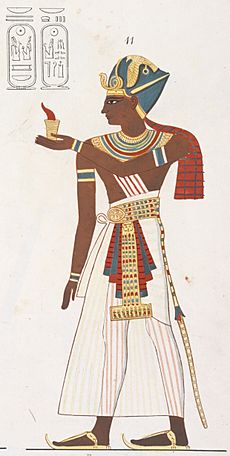

When Ramesses VI became king, he added his princely name, "Ramesses Amunherkhepeshef," to royal cartouches. He also added the titles he had before becoming king. These included "king's son," "crown prince," "royal scribe," and "cavalry general." He changed his youthful image on the carving to show an uraeus, a symbol of royalty. He also added the names of his brothers and sons to the carving.

For a while, some historians thought Ramesses VI might have been Ramesses III's grandson. They wondered if he was the son of an unknown prince or Pentawer, who was involved in a plot against Ramesses III. However, these ideas have been proven wrong. The carving clearly shows that Ramesses VI was the son of Ramesses III. Ramesses VI's mother was likely Iset Ta-Hemdjert, Ramesses III's main queen. This is suggested because Ramesses VI's royal names are found on a door frame in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens.

Ramesses VI's Wife and Children

Ramesses VI's main wife was Queen Nubkhesbed. Historians Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton believe she had four children with Ramesses VI:

- Prince Amenherkhepshef

- Prince Panebenkemyt

- Prince Ramesses Itamun (who became the future pharaoh Ramesses VII)

- Princess Iset

Princess Iset was given the important religious role of "Divine Adoratrice of Amun." A stone tablet found in Koptos tells about this appointment. It also shows that Nubkhesbed was indeed Iset's mother.

Prince Amenherkhepshef died before his father. He was buried in tomb KV13 in the Valley of the Kings. This tomb was first built for Chancellor Bay, an important official from an earlier dynasty. The tomb's decorations were updated for Amenherkhepshef, and some carvings mention Queen Nubkhesbed.

We know Ramesses VII was Ramesses VI's son from an inscription found in Deir el-Medinaeh. It says that Ramesses VII made a monument for his father, Ramesses VI.

Some historians, like James Harris, Edward F. Wente, and Kenneth Kitchen, have suggested that Ramesses IX was also a son of Ramesses VI. This would make him a brother to Ramesses VII. They note that Ramesses IX honored Ramesses VII on two offering stands. Ramesses IX also named one of his sons Nebmaatre, which was Ramesses VI's royal name. This might have been to honor his father. However, other scholars, including Dodson and Hilton, disagree. They think Ramesses IX was the son of Prince Montuherkhopshef, making him Ramesses VI's nephew.

Ramesses VI's Time as Pharaoh

How Long Did Ramesses VI Rule?

Ramesses VI became king shortly after Ramesses V died. Most historians agree that Ramesses VI ruled for eight full years. He also lived for about two months into his ninth year as king. For example, some historians suggest he ruled from 1156 BC to 1149 BC. Others give slightly different dates, like 1145–1137 BC or 1143–1136 BC.

In 1977, historians Edward F. Wente and Charles van Siclen first suggested that Ramesses VI ruled into his eighth year. This idea was confirmed by Jac Janssen, who studied an ancient piece of pottery. This pottery mentioned a loan of an ox in the seventh and eighth years of an unnamed king, who could only have been Ramesses VI. Later, Lanny Bell found more proof that Ramesses VI not only ruled into his eighth year but likely completed it and lived into his ninth.

An important ancient document, the Turin Papyrus 1907+1908, also helps us understand his reign. This papyrus covers the time from Ramesses VI's fifth year until Ramesses VII's seventh year. Historian Raphael Ventura's study of this document shows that Ramesses VI ruled for eight full years and died in his ninth. He was then followed by Ramesses VII.

Challenges and Changes in Egypt

Early Reign: Troubles in Thebes

Soon after becoming king, Ramesses VI and his court may have visited Thebes. This visit might have been for a festival or for the preparations for Ramesses V's burial. Ramesses VI visited Thebes at least one more time during his rule. That was when he appointed his daughter as Divine Adoratrice of Amun.

The situation in southern Egypt was not very stable when Ramesses VI became king. Records show that workers at Deir el-Bahari could not work on the king's tomb. This was because of "the enemy" nearby. This problem lasted for at least fifteen days in Ramesses VI's first year. This "enemy" was said to have robbed and burned the area of Per-Nebyt. The police chief of Thebes ordered the workers to stop and guard the king's tomb. It's not clear who these enemies were. They could have been Libyan Meshwesh, Libu people, Egyptian bandits, or even groups fighting in a civil war between supporters of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI.

A short military campaign might have happened. After Ramesses VI's second year, these troubles seemed to stop. This campaign might be linked to a statue of Ramesses VI holding a captured Libyan. It could also be connected to a carving at the Karnak temple showing Ramesses VI winning against foreign soldiers. This was the last such victory scene made in Egypt for a long time.

The names Ramesses VI chose when he became king also suggest military activity. His Horus name meant "Strong bull, great of victories, keeping alive the two lands." His Nebty name meant "Powerful of arms, attacking the myriads."

Later Reign: Royal Activities

After these events, in his second year, Ramesses VI finally buried Ramesses V. He used the tomb originally meant for Ramesses V. During this visit to Thebes, Ramesses VI appointed his daughter Iset as God's Wife of Amun. His mother, the vizier Nehy, and other officials were there. That same year, he reduced the number of workers on the king's tomb from 120 to 60. This had been changed by Ramesses IV. After this, the community of workers at Deir el-Medina slowly declined. The settlement was finally left empty in the next Twenty-first Dynasty.

Even with fewer workers, Ramesses VI ordered six tombs to be built in the Valley of the Queens. This might include finishing the tomb of his mother, Iset Ta-Hemdjert. We don't know if these tombs were finished, and they cannot be identified today.

At some point, a statue of Ramesses VI was placed in a shrine of Ramesses II at the temple of Hathor in Deir el-Medina. This statue was called "Lord of the Two Lands, Nebmaatre Meryamun, Son of Re, Lord of Crowns, Ramesses Amunherkhepeshef Divine Ruler of Iunu, Beloved like Amun."

A full description of this statue is on the back of the Turin Papyrus Map. This map is famous for being the oldest surviving map of its kind. The papyrus says the statue was made of painted wood and clay. It showed the pharaoh wearing a golden loincloth, a crown of lapis-lazuli and jewels, a golden uraeus, and sandals of electrum. The statue received offerings of incense and liquids every day. The papyrus is a letter to Ramesses VI asking for a certain man to be in charge of these offerings. The king seemed to approve, as the letter writer's grandson later held the title of "High Priest of Nebmaatre [Ramesses VI], Beloved of Amun."

Ramesses VI seemed to like these cult statues. At least ten statues and a sphinx of him have been found in Tanis, Bubastis, and Karnak. This is more than any other king of the Twentieth Dynasty after Ramesses III. The tomb of Penne, an Egyptian official in Nubia, says that Penne gave land to help pay for another cult statue of Ramesses VI. Ramesses VI was so pleased that he rewarded Penne.

Egypt's Economy Weakens

During the reigns of Ramesses VI, VII, and VIII, prices for basic goods, especially grain, went up a lot. As Egypt's economy got weaker, Ramesses VI started using the statues and monuments of earlier pharaohs. He often covered their names with plaster and then carved his own royal names over them. He especially did this to monuments of Ramesses IV in Karnak and Luxor. He also took over a statue of Ramesses IV, texts carved by Ramesses IV on an obelisk, and Ramesses V's tomb.

Historians say these actions don't necessarily mean Ramesses VI disliked his brother or nephew. He probably just wanted his own name to be seen in important places. Also, he left Ramesses IV's names untouched in many areas. This shows he wasn't trying to erase Ramesses IV from history.

There is some evidence that Ramesses VI did build new things. An inscription in Memphis says he built a large gateway of fine stone for the temple of Ptah. Ramesses VI boasted that he "covered all the land with great monuments in my name... built in honor of my fathers the gods." Overall, historian Amin Amer describes Ramesses VI as "a king who wished to pose as a great pharaoh in an age of unrest and decline."

Power Shifts in Egypt

Important Officials

We know some of Ramesses VI's important officials. These include:

- His finance minister, Montuemtawy, who had been in office since Ramesses III's reign.

- The vizier Neferronpe, who served since Ramesses IV's time.

- Neferronpe's son, the vizier Nehy.

- Amenmose, the mayor of Thebes.

- Qedren, the king's butler.

In the south, the troop commander of Kush was Nebmarenakhte. The administrator of Wawat (the land between the first and second cataracts of the Nile), mayor of Anîba, and controller of the Temple of Horus at Derr was Penne.

The Powerful Family of Ramessesnakht

In Thebes, the position of High Priest of Amun came under the control of Ramessesnakht and his family. This happened during Ramesses IV's reign. Ramessesnakht was officially Ramesses VI's Vizier of the South. His power grew, even though Ramesses VI's daughter Iset was also connected to the Amun priesthood. Ramessesnakht likely oversaw the building of Iset's tomb. Historians believe that Ramessesnakht and his family were the most powerful people in Egypt at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty. However, their actions did not seem to go against the king's interests.

Ramessesnakht often helped distribute supplies to workers. He controlled much of the work on the king's tomb. This might be because the High Priest of Amun's treasury was now helping to pay for these projects. Ramessesnakht's son, Usermarenakhte, became the Steward of Amun. He managed large areas of land in Middle Egypt. He also took over his grandfather Merybaste's role of controlling the country's taxes. This meant Ramessesnakht's family controlled both the royal treasury and the treasury of Amun. Other important religious jobs were given to people who married into Ramessesnakht's family.

Ramessesnakht was powerful enough to build one of the largest tombs in Thebes for himself. This was at a time when royal building projects, like Ramesses VI's temple, had been stopped. Historians now believe that Ramessesnakht and his family created a second center of power in Upper Egypt. This center worked with the kings of the Twentieth Dynasty, who ruled from Memphis and Pi-Ramesses in Lower Egypt. This made Thebes a religious and administrative capital, setting the stage for the rise of the Twenty-first Dynasty later on.

Egypt's Empire Abroad

Losing Control in Canaan

Egypt's political and economic decline continued during Ramesses VI's reign. He is the last king of the New Kingdom whose name is found on carvings and pillars at the temple of Hathor in Serabit el-Khadim in Sinai. He sent expeditions there to mine copper.

Egypt might still have had some influence or connections with its former empire in the Levant. This is suggested by a broken bronze statue base of Ramesses VI found in Megiddo in Canaan. Also, a scarab (a type of beetle-shaped amulet) of his was found in Alalakh on the coast of southern Anatolia.

However, Egypt's presence in Canaan ended during or soon after Ramesses VI's rule. The last Egyptian soldiers left southern and western Palestine around this time. The border between Egypt and other lands returned to a fortified line from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. A 2017 study confirmed that Ramesses VI's reign was the last time Egyptian military was present in Jaffa. Jaffa was destroyed twice around this period. The people fighting against Egyptian rule were local, likely from Canaanite cities. This opposition grew after the Sea People arrived in the region during Ramesses III's reign. Losing all these lands in Asia made Egypt's economy even weaker.

Holding On to Nubia

Egypt's control over Nubia seemed much stronger during this time. This might be because the local people had become more like Egyptians, or because Nubia was economically important. Ramesses VI's royal names have been found on Sehel Island near Aswan and in Ramesses II's temple in Wadi es-Sebua. Ramesses VI is also mentioned in the tomb of Penne in Anîba, near the Third Cataract of the Nile. Penne also talks about military raids further south, from which he claimed to bring back treasures for the pharaoh.

Ramesses VI's Burial Sites

The Royal Tomb: KV9

Ramesses VI was buried in the Valley of the Kings, in a tomb known as KV9. This tomb was first built for Ramesses V. Ramesses V might have been buried there for a short time. Then, he was likely moved to another, simpler tomb somewhere else in the Valley of the Kings, which has not been found yet. Ramesses VI ordered KV9 to be completely redone for himself. There was no space left for Ramesses V's permanent burial. Ramesses V was finally laid to rest in Ramesses VI's second year as king. This might have been because Thebes had become stable again. Taking over Ramesses V's tomb could mean Ramesses VI didn't think highly of his predecessor. It could also just mean he was trying to save money.

The new work on KV9 helped save the tomb of Tutankhamun. The entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb was buried under huts built for the workers on Ramesses VI's tomb. These works seem to have finished during Ramesses VI's sixth year. At that time, Ramessesnakht received copper tools, likely marking the end of the tomb's construction. If an ancient text refers to Ramesses VI, it suggests the tomb was ready in his eighth year. He might have been sick and close to death then. Once finished, the tomb was about 104 meters (341 feet) long. It included one of only three complete versions of the Book of Gates found in royal tombs. It also had a complete version of the Book of Caverns.

Within 20 years of Ramesses VI's burial, robbers likely broke into and looted the tomb. They even damaged Ramesses' mummy to get to his jewelry. These events happened during the reign of Ramesses XI. They are described in the Papyrus Mayer B, though the exact tomb mentioned isn't fully certain. Ramesses VI's mummy was later moved to the tomb KV35 of Amenhotep II. This happened during the reign of Pinedjem of the early Twenty-First Dynasty. The mummy was found there in 1898 by Victor Loret.

A medical check of the mummy showed that Ramesses VI died around age forty. His body was severely damaged. His head and torso were broken into several pieces by an axe used by the tomb robbers. A single female hand was found inside the mummy's wrappings.

In 1898, Georges Émile Jules Daressy cleared KV9, which had been open since ancient times. He found pieces of a large granite box and many parts of Ramesses VI's stone mummy-shaped sarcophagus. The face of this sarcophagus is now in the British Museum. The sarcophagus was put back together in 2004 after two years of work on over 250 pieces found in the tomb. It is now on display there.

In 2020, the Egyptian Tourism Authority released a full 3D model of the tomb online, with detailed photos. In April 2021, his mummy was moved from the Egyptian Museum to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. This was part of a big event called the Pharaohs' Golden Parade.

Ramesses VI's Mortuary Temple

Ramesses VI seems to have taken over a large mortuary temple in El-Assasif. This temple was originally for Ramesses V, who likely took it from his father, Ramesses IV. The temple was planned to be almost half the size of the one at Medinet Habu. It was only in its early building stages when Ramesses IV died. We don't know if it was ever fully completed. However, the temple is mentioned as owning land in the Wilbour Papyrus, which dates to Ramesses V's reign. Digs have shown that much of its remaining decoration was made under Ramesses VI.

See also

In Spanish: Ramsés VI para niños

In Spanish: Ramsés VI para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |