Dmanisi hominins facts for kids

The Dmanisi hominins were a group of early humans whose fossils were found in Dmanisi, Georgia. These fossils and stone tools are very old, dating back about 1.85 to 1.77 million years. This makes them the oldest well-dated human-like fossils in Eurasia (Europe and Asia). They are also the best-preserved early Homo fossils from one place. Even though scientists debate their exact classification, the Dmanisi fossils are super important for understanding how early humans moved out of Africa. We know about the Dmanisi hominins from over a hundred body fossils and five famous, well-preserved skulls, known as Dmanisi Skulls 1 to 5.

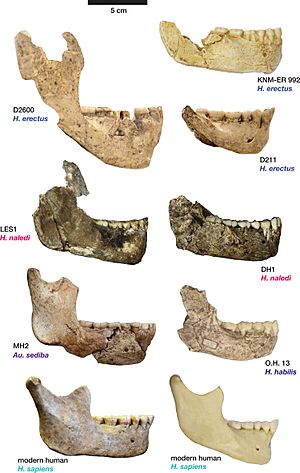

Scientists are still figuring out the exact species name for the Dmanisi hominins. This is because they had small brains and bodies, and their skeletons were quite simple. Also, the five skulls show a lot of differences among them. When they were first found, some thought they were an early type of Homo erectus or Homo ergaster. In 2002, a very large jaw (D2600) was found, which made some researchers think there might have been more than one type of human at the site. They even named a new species, Homo georgicus. However, later studies by the Dmanisi team suggested that all the skulls probably belong to the same species. They believe the differences are due to age and whether the individual was male or female. In 2006, the team suggested calling them H. erectus georgicus or H. e. ergaster georgicus. The debate about their name continues today.

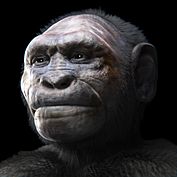

The Dmanisi hominins had a mix of features. Some parts of their bodies looked like later H. erectus and modern humans. But other parts were more like older human relatives, such as Australopithecus. Their legs were similar to modern humans, meaning they could walk and run long distances. However, their arms were more like those of Australopithecus and modern apes. The Dmanisi hominins were also smaller than later Homo species. They stood about 145–166 cm (4.8–5.4 ft) tall. Their brains were also small, ranging from 545–775 cubic centimeters. This brain size is more like Homo habilis than later H. erectus. All the skulls have large brow ridges and faces.

During the Ice Age (Pleistocene epoch), the climate in Georgia was wetter and had more forests than it does now. It was similar to a mediterranean climate. The Dmanisi fossil site was near an ancient lake. It was surrounded by forests and grasslands. Many different kinds of Ice Age animals lived there. The good climate at Dmanisi might have been a safe place for early humans. They could have reached it from Africa through a path called the Levantine corridor. The stone tools found at the site are from the Oldowan tradition. This is a very early type of tool-making.

Contents

Finding the Dmanisi Hominins

Digging Up History in Georgia

Dmanisi is in southern Georgia. It is about 85 kilometers (52.8 miles) from the capital city, Tbilisi. Dmanisi was a city in the Middle Ages. Because of this, people have been interested in digging there for a long time. The main archaeological site is in the ruins of the old city. It sits on a high point overlooking the Mashavera and Pinazauri rivers.

Archaeological digs started in 1936. In 1982, archaeologists found deep pits. Inside these pits, they discovered fossilized animal bones. The Georgian Paleobiological Institute was told about the find. So, in 1983, they began systematic digs to find fossils. These digs continued until 1991.

During the 1983–1991 digs, many animal fossils were found. They also found some stone tools. These tools were very old and simple. They were much more primitive than other tools found in Eastern Europe. Scientists used other animal fossils to guess their age. They thought the tools were from the Late Pliocene to the Early Pleistocene periods. Since 1991, Georgian scientists have continued digging. Specialists from the Romano-Germanic Museum in Cologne joined them.

Amazing Discoveries: Human Fossils!

In 1991, the expedition found many animal fossils and stone tools. On September 25, a group of young archaeologists found a mandible (lower jawbone).

The leaders of the expedition, Abesalom Vekua and David Lordkipanidze, came to the site. The next morning, they carefully removed the jawbone from the rock. It was a difficult process. Once it was free, they could clearly see it was a primate jaw. It had a full set of teeth that showed little wear. This suggested the primate was young, about 20–24 years old. They didn't know what species it was yet.

Back in Tbilisi, Vekua, Lordkipanidze, and Leo Gabunia studied the jawbone. They quickly realized it was from a hominid (a human-like creature). It had some simple features, but it was most similar to fossils of Homo, not older australopithecines. After much discussion, they decided the Dmanisi hominin was likely an early Homo erectus. This meant it was the earliest Homo found outside Africa. This idea was supported when the rocks below the fossils were dated to about 1.8 million years old.

Digs continued, but human remains were rare. In 1997, they found a foot bone from a hominin in the same layer as the jaw. More discoveries happened in May 1999. Heavy rain had damaged the site. An archaeologist named Gocha Kiladze found a small skull fragment. Later, more fragments were found. They were able to piece together an ancient human skull. That same year, a better-preserved skull was found. These two skulls helped scientists understand the Dmanisi hominins better. The first skull was called Skull 2 (D2282), and the second was Skull 1 (D2280).

After studying them for almost a year, scientists saw that these skulls were a bit different from H. erectus. They were closer to the earlier African species H. ergaster. Many people now see H. ergaster as an early African type of H. erectus. The discovery of these two skulls was big news around the world. For the first time, the Georgian fossils were widely accepted as the earliest known hominins outside of Africa.

More Amazing Finds: All Five Skulls

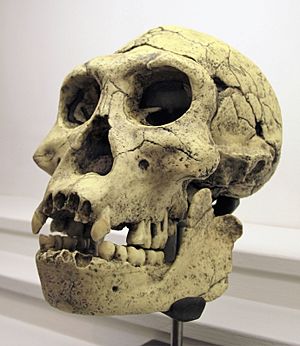

More discoveries followed. In 2000, another hominin jaw (D2600) was found. This one was in a slightly older layer of rock. This jaw was very large and had strong back teeth. The next year, Skull 3 (D2700) and its jaw (D2735) were found. They were almost perfectly preserved. Because its wisdom teeth were still coming in, Skull 3 was thought to be from a young person. In 2002, the skull of an old person, Skull 4 (D3444), was found. This person had lost almost all their teeth. Its jaw (D3900) was found in 2003. Both Skull 3 and Skull 4 had many simple, old features. The last skull, Skull 5 (D4500), was found in 2005. This skull matched the large jaw found in 2000. Scientists believe they came from the same person.

These skulls were important for many reasons. Skull 5 was the first complete adult hominin skull found from the Early Pleistocene. Skull 4 is the only toothless hominin found in such old sediments.

Besides the skulls, about a hundred other body fossils have been found. These include bones from the arms, legs, spine, and feet. Some of these bones were clearly from the same individual as Skull 3. They are from both young and adult individuals.

Together, the Dmanisi fossils are the most complete collection of early Homo fossils from one site. They all come from a similar time period. The variety in age (Skull 3 was young, Skull 4 was old) and likely sex gives us a unique look into how early human groups varied.

| Image | Skull & specimen number(s) | Brain Size | Found | Published | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dmanisi Skull 1 D2280 |

775 cc | 1999 | 2000 | Skullcap of an adult. Thought to be male because of its thick brow ridges. |

|

Dmanisi Skull 2 D2282 (jaw D211) |

650 cc | 1999 (jaw in 1991) |

2000 (jaw in 1995) |

Has delicate features. Thought to be the skull of a young female. |

|

Dmanisi Skull 3 D2700 (jaw D2735) |

600 cc | 2001 | 2002 | Skull of a young person. Generally delicate, but its upper canine teeth are large. Some features suggest it was male. |

|

Dmanisi Skull 4 D3444 (jaw D3900) |

625 cc | 2002 (jaw in 2003) |

2005/2006 | Skull of an elderly person who had lost almost all teeth. Thought to be male. |

|

Dmanisi Skull 5 D4500 (jaw D2600) |

546 cc | 2005 (jaw in 2000) |

2013 (jaw in 2002) |

Skull of an adult. This was the first complete adult early human skull found. Thought to be male because of its large features. |

What Species Were They?

The classification of the Dmanisi hominins is still debated. Scientists argue if they are an early form of H. erectus, their own species called H. georgicus, or something else.

Early Ideas About Classification

In 1995, the D211 jaw was described. Scientists thought it belonged to an early group of H. erectus. This was based on how its teeth looked, especially compared to African fossils. Some scientists noted that it had both old and new features. They suggested it was a more developed type of H. erectus, even though it was very old. Others pointed out that this mix of features is also seen in H. ergaster.

In 2000, Skulls 1 and 2 were described. Scientists noticed they looked like H. ergaster skulls. Many features suggested a close link to H. ergaster. These included the brow ridge, face shape, and skull width. These features usually help tell H. ergaster apart from Asian H. erectus. The Dmanisi fossils had a lower skull and thinner bones than Asian H. erectus. They also had a smaller brain size.

Scientists concluded that the Dmanisi fossils were part of the ergaster group. They thought it was possible that the Dmanisi hominins were ancestors of both later H. erectus in Asia and humans that led to H. sapiens.

Classifying After More Fossils Were Found

In 2002, Skull 3 (D2700) and its jaw (D2735) were described. Scientists found that even though it had a small brain like H. habilis, it mostly looked like a very small H. ergaster.

The D2600 jaw was also described in 2002. This jaw was very large and different from other human jaws found so far. It had a mix of old features (like Australopithecus) and newer features (like H. erectus). Scientists felt this was enough to create a new species, which they named Homo georgicus. They put all the Dmanisi hominins into this new species. They thought the big differences in size were because males and females looked very different (called sexual dimorphism). They believed H. georgicus was an early species that came from H. habilis and was a step towards Homo ergaster.

In 2005, one scientist supported the idea that all Dmanisi fossils belonged to the same species. They noted that even with different brain sizes, the skulls were not more different from each other than male and female gorillas are.

In 2006, scientists described Skull 4 and its jaw. They noted it was similar to the other fossils. They agreed that the Dmanisi hominins were ancestors to later H. erectus. That same year, a study of Skulls 1 to 4 and the D2600 jaw concluded that Skulls 1 through 4 were from the same species. But the D2600 jaw was still a question mark. They noted that while the fossils were somewhat like H. habilis in size, they had many more features like H. erectus. They concluded that if the H. habilis-like traits were just old features that stayed, then Skulls 1 to 4 could be part of H. erectus.

Some scientists argued that the differences between the D211 and D2600 jaws were too big for them to be the same species. They suggested two ideas: either it was one species with unusually high sexual dimorphism, or D2600 was a separate species (H. georgicus). A more detailed study in 2008 found that while the jaw differences were greater than in modern humans, they were similar to gorillas. They concluded that there was no strong reason to say the Dmanisi fossils were from different species. But they noted this species would have had more sexual dimorphism than later Homo.

Classification After Skull 5 Was Described

Skull 5, found in 2005 and described in 2013, was found to belong to the same individual as the D2600 jaw. Together, these two fossils showed an even wider range of shapes for the Dmanisi hominins. Scientists believed Skull 5 was part of the same group as the other Dmanisi fossils. They came from the same time and place. Their differences were similar to what you see in chimpanzees, bonobos, and modern humans.

The large variety in the Dmanisi fossils led scientists to suggest that the differences seen in other old human fossils might have been misunderstood. They thought these differences might not mean separate species. Instead, they could be variations within one evolving group of humans. With this in mind, they suggested that the African fossils (like H. ergaster) could be seen as a subspecies of H. erectus. Since Dmanisi hominins likely came from an early migration of H. erectus out of Africa, they suggested calling them H. e. e. georgicus.

However, other scientists disagreed in 2014. They questioned if the comparisons were detailed enough. They also questioned the methods used to decide what was species variation. They argued that just because the fossils were from the same site and time didn't mean they were all the same species. They concluded that at least the D2600 jaw, and thus Skull 5, should remain a distinct species, H. georgicus.

The Dmanisi research team responded. They maintained that the fossils represented a single species. They argued that if H. georgicus was a separate species, Dmanisi would have had at least four different human species. This would be very unusual for such a small area and short time. They said that the other scientists ignored previous studies. They also defended the name Homo erectus ergaster georgicus. They said it was used to show a local group of a subspecies.

A 2017 study of Skull 5 compared it to other Dmanisi skulls and to skulls of H. sapiens and other ancient humans. The study confirmed that the variation among Dmanisi fossils was not too much compared to other human groups. Some features, like certain face measurements, were even more varied in modern humans. The study found that the Dmanisi hominins "cannot clearly be called either H. habilis or H. erectus". This suggests there was a "continuum of forms" in early Homo. Skull 5 has many old features like H. habilis. Skull 1, with the largest brain, is more like African H. ergaster/H. erectus. This led scientists to think that H. erectus and H. habilis might be part of one evolving lineage. This lineage started in Africa and later spread to Eurasia.

When and Where They Lived

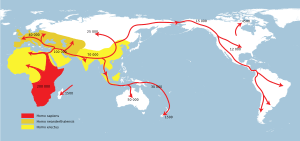

The exact time when early humans first left Africa is a big question. The Dmanisi hominins are the earliest known humans in Europe. The rocks where the Dmanisi fossils were found sit on top of volcanic rock. This volcanic rock has been dated to 1.85 million years old. The layers of sediment above it suggest that not much time passed between the volcanic eruption and the fossil deposits. Studies of Earth's magnetic field show the sediments are likely about 1.77 million years old. Fossils of other animals, like the rodent Mimomys, which lived from 2.0 to 1.6 million years ago, support this date.

In 2010, the Dmanisi fossil site was dated more precisely to 1.81 ± 0.03 million years old. This was slightly younger than the volcanic rock below. Since the D2600 jaw was found in a slightly lower layer, it might be even older. Stone tools found at Dmanisi range from 1.85 to 1.78 million years old. This suggests that humans lived at the site throughout this time.

During the late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene, Georgia might have been a safe place for human groups. The environment at Dmanisi was good for humans. It had a mild and varied climate. The Greater Caucasus mountains blocked cold air from the north. Humans probably reached Georgia through the Levantine corridor, a natural path from Africa. They might have settled at Dmanisi before moving elsewhere. Similar-aged animal fossils and stone tools have been found in Romania, the Balkans, and even Spain.

How They Looked

Their Skulls

The Dmanisi hominins had brain sizes ranging from 546 to 775 cubic centimeters. The average was 631 cc. This brain size is similar to H. habilis but smaller than what is usually seen in H. erectus and H. ergaster (800–1000 cc). Their brain-to-body-mass ratio was also lower. It was more like H. habilis and australopithecines.

There are several features that make Dmanisi hominins different from early Homo like H. habilis. These include their well-developed brow ridges, large eye sockets (orbits), and the shape of their skull.

Skull 5 is the only complete skull found at Dmanisi. It stands out from all other known early human fossils. It has a large, forward-jutting face and a small braincase. This combination of large teeth, a large face, and a small braincase is unique in early Homo. If the braincase and face of Skull 5 had been found separately, scientists might have thought they belonged to different species. Despite looking like older Homo from the outside, the inside of Skull 5's braincase is more similar to later H. erectus.

Overall, the Dmanisi hominins seem to have been small-brained individuals with strong brow ridges. Their height, body weight, and limb proportions were at the lower end of what we see in modern humans.

Their Bodies

Before the Dmanisi fossils were found, we knew very little about the body shapes of early Homo. Older human relatives like Australopithecus were small, about 105 cm (3.4 ft) tall. Their limb proportions were between modern humans and apes. Later Homo like "Turkana Boy" (a 1.55 million-year-old H. ergaster/H. erectus) had body proportions similar to modern humans. The Dmanisi fossils help fill in the gaps. They show how humans changed from walking on two legs (like Australopithecus) to always walking upright (like H. ergaster).

Based on their limb bones, the Dmanisi individuals were about 145–166 cm (4.8–5.4 ft) tall. They weighed about 40–50 kg (88–110 lbs). They were smaller than H. ergaster in Africa. This might be because they were more primitive or adapted to a different environment. Their leg proportions were similar to modern humans. But the actual length of their legs was more like later Homo than australopithecines. This suggests that walking and running skills improved gradually over time.

The way their arm bones were shaped suggests their arm movements and positions were different from modern humans. Their arms might have been more like those of earlier Homo or australopithecines.

Their spine was more similar to modern humans and early H. erectus than to australopithecines. The fossil vertebrae show they could bend their spine like modern humans. The strong vertebrae suggest they could run and walk long distances. Their feet were also similar to modern humans, though they might have walked with their feet closer together.

Their Environment

The fossils at Dmanisi give us a "snapshot in time." Most of the human fossils were found in a short time period, perhaps as short as 10–100 thousand years.

During the Ice Age, the Dmanisi site was near a lake. The environment was mild, wet, and forested. It had woodlands, open grasslands, and rocky areas with shrubs. This was different from the dry, hot grasslands of East Africa, where other early humans lived. Even then, Dmanisi was probably warmer and drier than Georgia is today, similar to a mediterranean climate.

Most animal fossils suggest a mix of forest and grassland. But some show areas that were full steppe (like ostrich fossils) or full forest (like deer fossils). Forests likely covered the mountains and river channels. Flat river valleys had grassland. Deer fossils are very common, suggesting forests were the main environment.

Many different animals lived at Dmanisi. These included pikas, lizards, hamsters, tortoises, hares, jackals, and fallow deer. Several extinct species were also present. These included two types of saber-toothed cats (Megantereon and Homotherium), the European jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis), and a giant ostrich (Pachystruthio dmanisensis). The presence of so many large meat-eaters shows the environment was very diverse. It's possible that these carnivores helped gather the human skulls in one small area.

Many fossilized plant seeds were also found. Some were from edible plants like Celtis (hackberries) and Ephedra. Hackberries are found at other early human sites too. This suggests Dmanisi hominins might have eaten them. Besides berries and fruit, they probably ate a wide range of foods. Meat was likely a big part of their diet, especially in winter.

Their Way of Life

Tools They Used

Over 10,000 stone tools have been found at Dmanisi. Their location suggests that humans lived there many times. The tools are simple, much like the Oldowan tools made in Africa almost a million years earlier. Most are flake tools, but some lithic cores and choppers were also found. They likely got the raw materials for these tools from nearby rivers.

The presence of cores, flakes, and finished tools shows that all stages of knapping (shaping stone into tools) happened at Dmanisi. They used good quality rocks. The technique wasn't fancy, but they adapted it to the shape of each stone.

Many unmodified stones were also found. These stones must have been brought to the site by humans. Larger stones might have been used to smash bones, cut meat, and pound food. Smaller stones could have been used for other things, like throwing. These collections of moved stones suggest that humans stored them to avoid repeated trips to gather more.

Working Together

Scientists think the small Dmanisi hominins might have used aggressive scavenging. They might have thrown small rocks to steal food from local meat-eaters. This "power-scavenging" might have been done in groups for protection. It could have led to social cooperation within families.

There is also indirect evidence of social cooperation from Skull 4. This individual had lost all but one tooth by the time he died. He would have lived for several years after losing his teeth. This is shown by the bone tissue that filled his tooth sockets. Without fire to cook food, it would have been hard for a toothless person to survive in a cold environment. While he might have eaten soft animal parts like brains, it's more likely that other members of his group cared for him.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Homo georgicus para niños

In Spanish: Homo georgicus para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |