Douay–Rheims Bible facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Douay–Rheims Bible |

|

|---|---|

| 1609_Doway_Old_Testament.pdf | |

| Full name: | Douay Rheims Bible |

| Abbreviation: | DRB |

| Language: | Early Modern English |

| NT published: | 1582 |

| OT published: | 1609-1610 |

| Derived from: | Vulgate |

| Textual basis: | NT: Vulgate. OT: Vulgate. |

| Translation type: | Formal equivalence translation of the Jerome Vulgate compared with Hebrew and Greek sources for accuracy. Subsequent editions use the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate. Used as interlinear bibles in diglots for the respective Vulgate versions. |

| Reading level: | University Academic, Grade 12 |

| Copyright status: | Public domain |

| Religious affiliation: | Catholic Church |

|

Genesis 1:1-3

In the beginning God created heaven, and earth. And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters. And God said: Be light made. And light was made. |

|

|

For God so loved the world, as to give his only begotten Son; that whosoever believeth in him, may not perish, but may have life everlasting. |

|

The Douay–Rheims Bible is an important English translation of the Bible. It was created by members of the English College, Douai for the Catholic Church. This Bible was translated from the Latin Vulgate version.

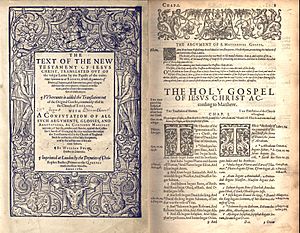

The New Testament part was published in Reims, France, in 1582. It came with many notes and comments. The Old Testament part was published later, in two volumes, in 1609 and 1610. The first volume covered books from Genesis to Job. The second volume included Psalms to 2 Maccabees and some other books.

The main goal of this Bible was to support Catholic traditions. It was made during a time when the Protestant Reformation was changing religion in England. The language used in the first Douay–Rheims Bible was quite old and hard to read. Because of this, it was later updated by Bishop Richard Challoner in the mid-1700s. This updated version is still known as the Douay–Rheims Bible.

Today, other Bibles like the Jerusalem Bible are more common in English-speaking Catholic churches. However, the Challoner revision of the Douay–Rheims Bible is still preferred by many traditional Catholics.

Contents

- Why was the Douay–Rheims Bible created?

- What was the style of the Douay–Rheims Bible?

- How did the Douay–Rheims Bible influence others?

- Challoner's Revision

- How are the book names different?

- How did the Douay–Rheims influence the King James Version?

- Douay–Rheims Only movement

- Modern Harvard-Dumbarton Oaks Vulgate

- See also

Why was the Douay–Rheims Bible created?

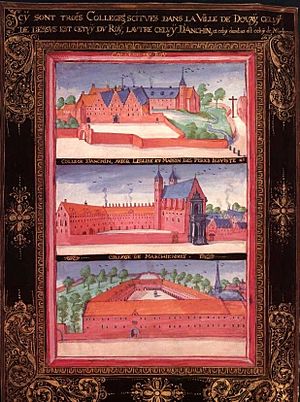

After the English Reformation, some Catholics left England and moved to Europe. A main center for English Catholics was the English College, Douai in Douai, France. This college was started in 1568 by William Allen. Its purpose was to train priests to help bring England back to Catholicism. This is where the Catholic translation of the Bible into English was made.

The New Testament was printed in 1582. It is often called the Rheims New Testament because the college was temporarily in Reims at that time. The main translator was Gregory Martin. He was helped by others like William Allen and Richard Bristow. The Old Testament was ready around the same time. But there wasn't enough money to print it until later. It was finally published in 1609 and 1610, after the college returned to Douai. This is why it's known as the Douay Old Testament.

The Rheims New Testament actually influenced the translators of the King James Version. This shows how important it was. Even though the cities are now spelled Douai and Reims, the Bible is still called the Douay–Rheims Bible. It has also been the basis for other Catholic Bibles in English.

The translators faced challenges in printing. They also worked to make sure the Latin text matched other versions. The final official Latin text, called the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, came out in 1592. The translators of the Douay–Rheims Bible made sure their English version matched this Latin text.

What was the style of the Douay–Rheims Bible?

The Douay–Rheims Bible is a translation of the Latin Vulgate. The Vulgate itself was translated from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts. Saint Jerome created most of the Vulgate around 345–420 AD. The Council of Trent later declared his translation to be the official Latin Bible.

The Catholic scholars who made the Douay–Rheims Bible looked at the original Hebrew and Greek texts. They also checked "other editions in diverse languages." However, their main goal was to translate very literally from the Latin Vulgate. They believed this would make it more accurate. This literal style sometimes made the English sound stiff or very Latin-like.

Here is an example from Ephesians 3:6–12 from the original 1582 Douay-Rheims New Testament:

The Gentiles to be coheires and concorporat and comparticipant of his promise in Christ JESUS by the Gospel: whereof I am made a minister according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given me according to the operation of his power. To me the least of al the sainctes is given this grace, among the Gentils to evangelize the unsearcheable riches of Christ, and to illuminate al men what is the dispensation of the sacrament hidden from worldes in God, who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God, may be notified to the Princes and Potestats in the celestials by the Church, according to the prefinition of worldes, which he made in Christ JESUS our Lord. In whom we have affiance and accesse in confidence, by the faith of him.

The Rheims New Testament also used some of the English wording from earlier Protestant versions. For example, it used parts of William Tyndale's translation from 1525. It also adopted readings from the Protestant Geneva Bible and the Wycliffe Bible. The Wycliffe Bible was translated from the Vulgate, just like the Douay-Rheims.

Most modern Bible versions, both Protestant and Catholic, translate directly from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts. They do not use a secondary version like the Vulgate. However, the Douay-Rheims translators believed the Vulgate was better. They thought that the original language manuscripts available in their time had errors. They also pointed out that the Council of Trent said the Vulgate was free of errors in its teachings.

The translators chose to use Latin-sounding words for religious terms instead of everyday English. They believed Latin terms were more precise. They also wanted their translation to be very faithful to the Latin text. This meant that if the Latin was hard to understand, the English translation would also be hard to understand. They thought that if the original text was unclear, the translation should also be unclear. This way, readers would need to look at the notes for explanations.

The Douay-Rheims Bible was also created to argue against Protestant translations. Before it, only Protestant Bibles were available in English. The Douay-Rheims included all the books accepted by the Catholic Church.

How did the Douay–Rheims Bible influence others?

In England, a Protestant named William Fulke accidentally made the Rheims New Testament popular. He published the Rheims text and its notes side-by-side with the Protestant Bishops' Bible. Fulke wanted to show that the Catholic version was worse than the Bishops' Bible. But his book, first published in 1589, made the Rheims text easy for everyone to read without getting into trouble.

The Rheims translators also made a list of unfamiliar words they used. Some examples include "acquisition," "adulterate," "advent," "allegory," "verity," "calumniate," "character," "cooperate," "prescience," "resuscitate," "victim," and "evangelise." They also kept some Greek or Hebrew terms instead of translating them. For example, they used "azymes" for unleavened bread and "pasch" for Passover.

Challoner's Revision

What changes did Challoner make?

The original Douay–Rheims Bible was published when Catholics faced difficulties in Britain. Owning the Bible was even a crime. By the time it was safe to own, the English used in the Bible was very old. So, Bishop Richard Challoner, with help from Father Francis Blyth, greatly "revised" it between 1749 and 1777.

Challoner's changes borrowed a lot from the King James Version. He was familiar with its style because he had converted from Protestantism to Catholicism. Challoner fixed the strange language and many of the Latin-sounding words. His version, while still called the Douay–Rheims, was quite different. He removed most of the long notes and comments from the original. He also kept all 73 books of the Vulgate, except for Psalm 151. He wanted to make the Bible easier to read and understand. He rephrased old or unclear terms and removed meanings that were intentionally confusing in the original.

Here is the same passage from Ephesians 3:6–12 in Challoner's revision:

That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs and of the same body: and copartners of his promise in Christ Jesus, by the gospel, of which I am made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given to me according to the operation of his power. To me, the least of all the saints, is given this grace, to preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ: and to enlighten all men, that they may see what is the dispensation of the mystery which hath been hidden from eternity in God who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God may be made known to the principalities and powers in heavenly places through the church, according to the eternal purpose which he made in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.

When was Challoner's revision published?

Challoner released a New Testament edition in 1749. He then published the whole Bible in 1750, making more changes to the New Testament. He released another New Testament version in 1752, which had about 2,000 differences from the 1750 edition. This 1752 version became the main text for later editions during his lifetime.

In all three editions, the many notes and comments from the 1582/1610 original were greatly reduced. This made the Bible a smaller, single-volume book, which made it much more popular. The long paragraphs were also broken up, so each verse became its own paragraph. The three extra books that were in an appendix of the Old Testament were removed. Later editions of Challoner's revision mostly kept his 1750 Old Testament with very few changes.

Challoner's 1752 New Testament was further revised by Bernard MacMahon in Dublin between 1783 and 1810. These Dublin versions are the source for many Challoner Bibles printed in the United States in the 1800s. Most 20th-century printings and online versions of the Douay–Rheims Bible follow Challoner's earlier New Testament texts from 1749 and 1750.

The Challoner version was officially approved by the Church. It remained the main Bible for most English-speaking Catholics until the late 1900s. It was first published in America in 1790. Many American editions followed. One famous edition was published in 1899, approved by Cardinal James Gibbons. This edition included a timeline that matched the idea of young-earth creationism. In 1914, a new edition was published with a different timeline that fit newer Catholic scholarship.

After 1943, Pope Pius XII allowed new Catholic Bible translations to be made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek. Because of this, the Douay–Rheims/Challoner Bible was replaced by newer English translations. The Challoner revision eventually stopped being printed by the late 1960s. It only came back into print when TAN Books reprinted the 1899 edition in 1971.

How are the book names different?

The names, numbers, and chapters of the books in the Douay–Rheims Bible and Challoner revision follow the Latin Vulgate. This means they are different from the King James Version and other modern Bibles. This can make it tricky to compare them directly.

For example, the books called Ezra and Nehemiah in the King James Version are called 1 and 2 Esdras in the Douay–Rheims Bible. The books called 1 and 2 Esdras in the King James Version are called 3 and 4 Esdras in the Douay, and were considered extra books.

The Psalms in the Douay–Rheims Bible follow the numbering of the Vulgate and the Septuagint. The Psalms in the King James Version follow a different numbering system. Here is a quick look at how the Psalm numbers match up:

| Douay–Rheims | King James Version |

|---|---|

| 1–8 | |

| 9 | 9–10 |

| 10–112 | 11–113 |

| 113 | 114–115 |

| 114–115 | 116 |

| 116–145 | 117–146 |

| 146–147 | 147 |

| 148–150 | |

How did the Douay–Rheims influence the King James Version?

The Old Testament part of the Douay Bible was published too late to influence the King James Version. However, the Rheims New Testament had been available for over twenty years. It was easy to access, especially through William Fulke's side-by-side version. Even so, the official instructions for the King James Version translators did not list the Rheims version as one to consult.

There has been much discussion about how much the King James Version used the Rheims version. Some scholars believe it had a very big influence. Others think the influence was small compared to the Bishops' Bible and the Geneva Bible.

In 1969, Ward Allen published some notes from the King James Version review committee. These notes showed that the committee sometimes used readings from the Rheims text. They did this especially when the original text was unclear. The King James Version also often used Latin-sounding words found in the Rheims version. Many of these Latinisms could have come from earlier English Bibles, but they were most easily found in Fulke's parallel editions. This also explains why some striking English phrases from the Rheims New Testament, like "publish and blaze abroad" at Mark 1:45, ended up in the King James Version.

Douay–Rheims Only movement

Some people strongly believe that the Douay–Rheims Bible is the best and most accurate English translation. They prefer it over all other English Bible versions. However, some experts, like Jimmy Akin, disagree. They argue that while the Douay is important in Catholic history, it should not be seen as the only true translation. This is because new discoveries and research have changed how we understand ancient texts.

Modern Harvard-Dumbarton Oaks Vulgate

Harvard University Press and Dumbarton Oaks Library have used Challoner's Douay–Rheims Bible for a special project. They used it as the English text in a Latin-English Bible. They also used the English text of the Douay–Rheims to help reconstruct the older Latin Vulgate that the Douay–Rheims was based on. This was possible because the Douay–Rheims, even Challoner's revision, tried to translate the Vulgate word-for-word.

One example of this literal translation is the Lord's Prayer. The Douay–Rheims has two versions. In Luke, it says "daily bread" (translating the Latin quotidianum). But in Matthew, it says "supersubstantial bread" (translating supersubstantialem). Every other English Bible uses "daily" in both places. This is because the original Greek word is the same, but Saint Jerome translated it in two different ways. He did this because the exact meaning of the Greek word epiousion was unclear then, just as it is now.

Some critics have said that the Harvard–Dumbarton Oaks project is unusual. They question why Challoner's 18th-century revision was used instead of a new translation into modern English. They also note that the Latin text they created is not a true medieval text or a critical edition.

See also

- Latin Vulgate

- Council of Trent

- Dei Verbum

- Liturgiam Authenticam

- Motu Proprio

- Sacrosanctum Concilium

- George Leo Haydock

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |