Douglas Grant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Douglas Grant

|

|

|---|---|

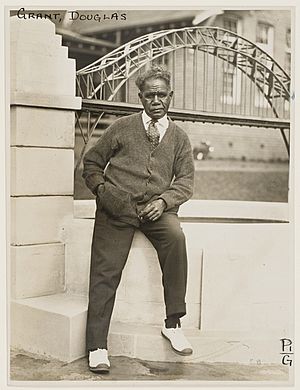

World War I veteran Douglas Grant sitting on the wall of a commemorative model of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Callan Park, where he worked as a clerk. Photo taken by Sam Hood in 1931.

|

|

| Born | 1885 Atherton |

| Died | December 4, 1951 (aged 65–66) Little Bay |

| Buried |

Botany Cemetery

|

| Allegiance | Australian |

| Army | |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 13th Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Relations | Robert Grant and Elizabeth Grant, foster brother Henry S Grant |

| Other work | Labourer |

Douglas Grant (born 1885, died 1951) was an amazing Aboriginal Australian man. He was a soldier, an artist who drew plans, a public speaker, and a writer. During World War I, he was captured by the German army. He became a prisoner of war in camps like Wittenberg and Wünsdorf, near Berlin.

Contents

Douglas Grant's Early Life

Douglas Grant was born around 1885 in north Queensland. He was from the rainforest Indigenous Nations near Malanda. When he was a baby, he became an orphan. This happened because of violence against Aboriginal people.

He was later cared for by Robert Grant and his wife Elizabeth. They named him Douglas. They took him to Lithgow, New South Wales, and then to Annandale, New South Wales.

Growing Up and Learning Skills

Douglas went to Annandale public school. He learned to be a draughtsman, which means he drew technical plans. He worked at Mort's Dock & Engineering in Sydney.

In 1913, he worked as a wool classer near Scone, New South Wales. People at the time admired his education. They also noted his love for Shakespeare and poetry. He was also an artist and played the bagpipes very well.

Douglas Grant in World War One

Douglas Grant joined the Australian Army in 1916. At first, he was discharged because Aboriginal people were not allowed to serve. But as more soldiers were needed, these rules were often ignored.

He re-enlisted in August 1916. He was sent to France to join the 13th Battalion. Douglas Grant was one of over 1,000 Indigenous men who fought in World War I.

Captured as a Prisoner of War

On April 11, 1917, during the First Battle of Bullecourt, Grant was wounded. He was then captured by the German army. He was sent to Wittenberg, a prisoner of war (POW) camp.

Food was very scarce at Wittenberg. His fellow POW, Harry Adams, remembered Douglas's humor. Douglas once asked a doctor if he had to "turn white" to look sick.

Studied by Scientists in Camp

Douglas was later moved to the Wünsdorf POW camp. German scientists studied him and other colonial soldiers. They wanted to learn about their languages and cultures. Douglas said they "measured him all over."

A German sculptor, Rudolf Marcuse, even made a bronze statue of Douglas. This important artwork was found again in 2015.

Helping Other Prisoners

While in the camp, Douglas became president of the British Help Committee. This group was part of the Red Cross. He helped get food and medicine for other prisoners. He especially helped Indian and African prisoners.

He wrote letters to different aid groups for his fellow prisoners. He worked to support the well-being of British colonial troops.

Returning Home

In December 1918, Douglas was sent from Germany to England. He visited his adoptive father's family in Scotland. He could even mimic a Scottish accent.

In 1919, he sailed back to Australia. He arrived in Sydney in June. He was officially discharged from the army in July. He went back to his old job as a draughtsman at Mort's Dock.

Life After the War

After the war, Douglas Grant left Mort's Dock. He moved to Lithgow. He worked in a paper factory and later at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory. He became the Secretary of the Lithgow RSL. He worked to help returned soldiers find jobs.

Even after his war service, Douglas faced racism. A colleague remembered that he had to check his tools. He did this to make sure no one had damaged them with a blow-torch.

Public Speaking and Advocacy

During the 1920s, Douglas became a popular public speaker. He gave talks about his war experiences. He also spoke about Aboriginal rights. He highlighted the important role of women in society.

He was known for telling stories and playing the bagpipes. He also recited poems by Robert Burns and Australian poets like Henry Lawson. He was even friends with Henry Lawson.

In 1929, Douglas wrote an important newspaper article. It was called A Call for Justice. He wrote about the 1928 Coniston massacre. He called it "a great unparalleled crime." He urged the government to protect Australia's original inhabitants.

He protested when a football club refused to play against an Aboriginal team. He famously said, "the colour line was never drawn in the trenches." He continued to advocate for Indigenous rights. He was also a regular guest on radio 2LT Lithgow's Diggers Show. Many people saw him as a "bridge-builder" between communities.

Later Years and Passing

In 1931, Douglas faced many challenges. He suffered from "shell shock" (now known as post-traumatic stress disorder). He also dealt with racism and unstable work. He was admitted to Callan Park Mental Hospital.

While there, he designed and built a Sydney Harbour Bridge replica. It was a memorial to fallen soldiers of World War I. This memorial still stands today. He also played golf and bowls. He was released in 1939.

In his later years, Douglas lived with relatives and friends. He stayed in Sydney, Lithgow, and towns along the coast. He also lived at the Salvation Army's old men's quarters. After 1950, he lived at the Bare Island War Veteran's Home.

Douglas Grant passed away on December 4, 1951. He is buried at Botany Cemetery. He never married or had children.

Douglas Grant's Legacy

Douglas Grant's life has inspired many. A character in the play Black Diggers (2013) is based on him. The journalist Paul Daley has written many articles about Douglas.

In 2021, historian John Ramsland published a book about him. It is called The Legacy of Douglas Grant: A Notable Aborigine in War and Peace. Filmmaker Tom Murray has also made documentaries about Douglas. These include an ABC Radio National feature and an award-winning film called The Skin of Others.

Australian actor Tom E. Lewis played Douglas Grant in these documentaries. A song from the film, "Ballad of the Bridge Builders," won an award in 2020. Archie Roach performed this song.

The Douglas Grant Park in Annandale is named in his honor.

Images for kids

-

World War I veteran Douglas Grant sitting on the wall of a commemorative model of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Callan Park, where he worked as a clerk. Photo taken by Sam Hood in 1931.